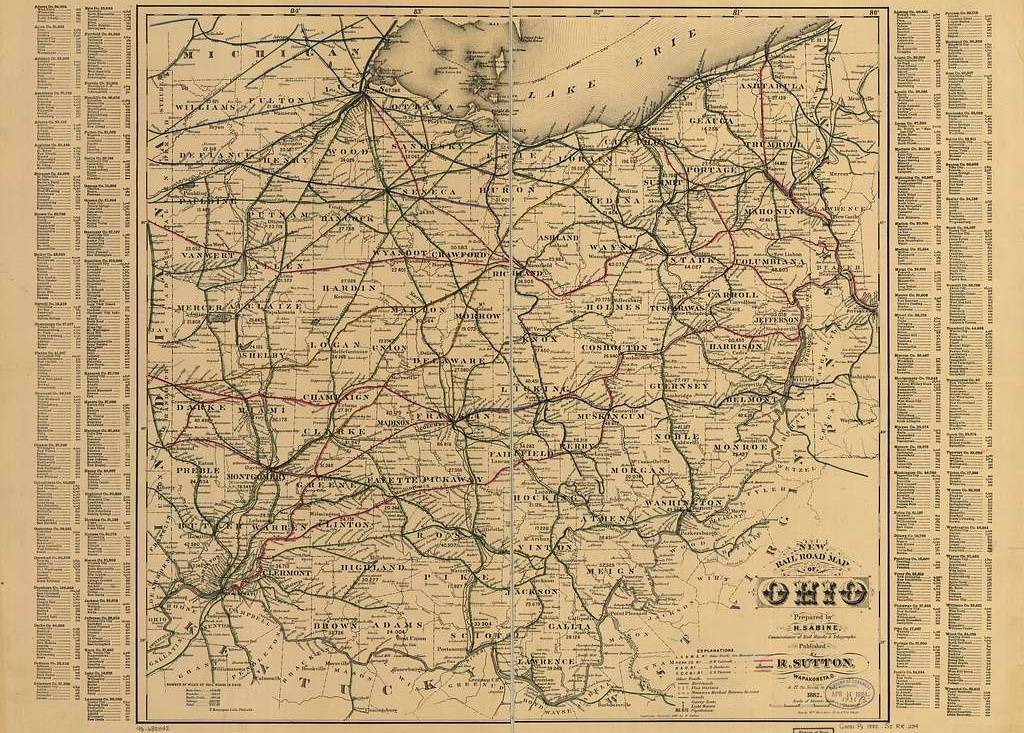

Should you find yourself traveling South-East from Cincinnati either along US Route 52 by car, or down the Ohio River via boat, you will come to a small community called Utopia. If you were to stop and look around a bit, you won’t find much there – a few residential houses, a village market, and little else. But, if you look a little deeper, you just might discover that not everything is what it seems. And the deeper you look (in more ways than one) the more interesting it becomes.

But, first, we need to take a look at Utopias in general, although maybe not this particular one.

What Is Utopia?

If you could picture a Utopia, what would it be like?

By definition, Utopia is a perfect society. The problem is that not everyone can agree on what that perfect society would be like. And even if they could, nobody has any clue about how to make that happen.

To one person, Utopia might mean living in a secluded cabin in the middle of nowhere without the constant sound of traffic, without drunken bastards puking on the sidewalks, and where your nearest neighbors don’t watch that Buffy The Vampire Slayer movie all night with their sound systems as loud as they can possibly be. However, to someone else, that may sound like a nightmare. (Except, golly, can’t my neighbor watch something else this Saturday? Something with … a little less spandex, maybe?)

I’m not sure what my idea of Utopia would be like … some place with fast internet, a huge library, an endless supply of Milk Chocolate, and neighbors who all look like they made the People Magazine’s Sexiest People Alive list. … um … Sorry, what were we talking about again? I think I got lost in a daydream.

The term “Utopia” was coined in 1516 by Sir Thomas More, which he took from a Greek word that translates to “No Place” although that’s not to say that it hasn’t stopped some people from trying to make such a place. However, the concept of Utopia existed long before then.

In 391 BC, Aristophanes wrote a play called Assemblywoman. As far as Greek plays go, this one might not be among the most well-known, but it is (at least) known for a few things. First, it’s known for containing the longest word in the Greek language: Lopadotemachoselachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypotrimmatosilphiokarabomelitokatakechymenokichlepikossyphophattoperisteralektryonoptekephalliokigklopeleiolagoiosiraiobaphetraganopterygon (and you thought some English words were hard to spell) which is actually some kind of seafood dish that I think is far too disgusting for me to write about, and right now I’m wondering why my spellcheck program isn’t causing a fit. The other thing this play is known for is being among the first public works to portray some kind of Utopian society. Of course, the play is a farce and a satire, and the Utopia it describes sounds a lot like pre-Marx communism. In a few years, Plato would take up the topic of utopias in works like Laws and The Republic (not to be confused with a work with the same name by Zeno of Citium written a few years later, which tries to paint Utopia in a more stoic light.)

By the 18th Century, Utopian ideas were still showing up in works like Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe and Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. And in more recent times, authors like Arthur C. Clark would tackle the subject in works like Childhood’s End or 3001: The Final Odyssey. Starhawk’s The Fifth Sacred Thing and Lois Lowry’s The Giver are probably also worth checking out.

In American History, the 19th Century was one of expansion. People began to relocate westward from the original colonies, buying up property and setting up communities. Some of these new communities were all about farming or mining or lumber mills. Sometimes, communities were based on particular religious teachings or ideologies. And, sometimes it was an attempt to create some form of “Utopian” community.

Just like we read in literature – in reality these utopian communities aren’t all that successful.

Utopia, Ohio – Community One – The Clermont Phalanx

François Marie Charles Fourier was a French writer and philosopher who, based on his own life history, came up with his own Utopian ideas. He believed that a society based on cooperation and concern for your fellow man could be achieved. The idea was that if people worked together (cooperation) they could be recompensed for their labor based on their contribution. These communities would be called Phalanxes, or communities centered around “Phalanstères” or big hotel-like structures where those who contributed the most (or those who were richest) would live in the nicer units while those who contributed less (or those who were poorer) would reside in the less-wanted. What work one did for the community (and therefore how rich or poor the person would prove to be) would be based not just on what they were able to do, but also on the type of things they actually enjoyed doing. Although, it should also be noted that for the most part, all the jobs that nobody wanted to do tended to be the highest paying while those doing the more popular jobs were rewarded quite a bit less.

On May 9, 1844, a group of roughly 150-200 people boarded the steamboat Yucatan in Cincinnati and headed about thirty miles downstream where they had a major party to kick off the start of a new planned community – one based on the teachings of Charles Fourier. Among them was a gentleman named A. J. MacDonald, a Scottish-born bookbinder with a particular interest in communes. He had been visiting a number of these communities, talking with people, and had planned on writing a book about them at some point. (Sadly, before he could do this, he died of Cholera.) Supposedly, a good time was had by all who enjoyed fine music, several speeches, and a commune version of a potluck dinner. Most of the people returned to their homes in Cincinnati, but a number of men stayed behind to start building the community.

MacDonald did return two months later. After a cold meal and a few speeches, he walked around the property to see how things were going. Work had been completed on a “temporary house” featuring a large dining room and a number of smaller rooms suitable for two single guys or a married couple. These accommodations were considered less than ideal, but MacDonald wrote in his notes that the men seemed to be enduring them well. The only building they were currently working on was a sawmill and once that was done they would begin working on more permanent housing. At this time, 120 people resided in the Clermont Phalanx.

The other thing MacDonald noticed was that things weren’t quite as nice as he thought it would be. First off, there seemed to be quite a bit of petty jealousy going on, especially between the women and the available men. Also, thanks to a lack of planning, there was a lot of bickering over minor disagreements, and nobody knew how to handle situations that should have been predictable. All of the residents had barely known each other before moving into the community, causing people to feel isolated and unsure of who was supposed to do what and when.

He also found out that the community was having some financial issues, too. Not all the residents were paying their dues in a timely fashion, the materials they needed to purchase cost more than they were expecting, and of the $17,000 supporters had pledged to pay, only $6,000 had come in.

Considering the living conditions weren’t up to par, nobody was all that happy, money wasn’t coming in like anybody planned – the community didn’t even last two years. In November 1846, The Clermont Phalanx collapsed. A few people chose to remain, but most people had enough and left.

A few years later, after MacDonald’s death, a man named John Humphrey Noyes acquired MacDonald’s notebooks. He used these notebooks to publish his own work, History of American Socialisms in 1872. The residents of the Clermont Phalanx didn’t keep records of any sort, and with little interaction with people outside the Fourite communities, the Noyes’ book contains the most extensive history of the Phalanx.

Utopia, Ohio – Community Two – Excelsior

John Otis Wattles purchased what had been the central portion of the Clermont Phalanx in hopes of building a community he wanted to call Excelsior. Prior to this, he had a history of living in and helping various commune communities (all of which failed). Wattles was familiar with the teachings of Fourier but did not necessarily follow the teachings himself.

Wattles’ big things included the anti-slavery movement (and we’re pretty sure he was strongly involved with The Underground Railroad in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois). But, more so, he was a spiritualist.

Today, when we think about the Spiritualist Movement, we tend to focus on the charlatans and pretend psychics who practiced things like table tipping and creating photos of themselves regurgitating cheesecloth and calling it ectoplasm. It is true that there was quite a bit of fraud that happened around this time, and maybe if we do not happen to believe in ghosts and mediums being able to speak with the dearly departed, it’s easy for some to dismiss the entire Spiritualism movement as nothing but nonsense.

However, Spiritualism was about more than just that. In many ways, it was a philosophy, a way of seeing things and trying to explain natural and supernatural phenomena based on how things were understood at the time. For example, some spiritualist beliefs stem from the work of German physician Franz Mesmer who theorized a connection between all animated and inanimate objects he called “animal magnetism” which spiritualists believed extended into the afterlife. Another principle of this magnetism is a large part of what we, today, call hypnosis. But, in Mesmer’s time, getting someone to cluck like a chicken after hearing the word “egg” (and after the subject entered some form of trance) seemed a lot like magic but today it’s a fairly common hypnotic trick that nearly anyone can perform with the right knowledge.

John O. Wattles believed that the communal philosophies of both the Fournier and the spiritualists had a lot in common and he was able to convince a few of the Phalanx residents to join his new community Excelsior. Although, to be fair, he’d just purchased the middle portion of the land they had all been using, so maybe that helped a bit, too.

One of Wattles’ first tasks as leader of this new community was to relocate the great dining hall and meeting room to a new spot, practically on the shore of the Ohio River. Why he felt this was a good idea (or why nobody tried all that hard to stop him) remains to be seen, and the building was taken apart, moved a short distance, and rebuilt next to the river. I should also note that this happened in haste with Wattles fearing the winter months which were also at hand. (What could possibly go wrong?)

On December 13, 1847, as everyone gathered inside the dining hall for an evening of dancing and spiritualism talks as a cold storm raged outside, the Ohio RIver began to flood around them. Then, at approximately eight o’clock in the evening, owing to a combination of the flood waters and the weight of the recently fallen snow on the roof, the building collapsed and seventeen of the thirty-two Excelsior residents died.

Wattles and his wife were among the survivors, and they announced they would quickly rebuild their community, but the damage to their reputations was already spreading through the rumor mills. Further floods happened that winter and into spring, and after a fire damaged several buildings, the Wattles gave up, packed their bags, and headed to Kansas, where John’s brother was living at the time.

Utopia, Ohio – Community Three – Utopia

The next person to enter this story was a guy named Josiah Warren. He, too, had an interest in communal societies.

In 1824, Josiah and his wife Caroline moved from Boston to New Harmony, Indiana to live in a commune built by his mentor, Welsh-born Robert Owen, where he worked as an orchestra conductor and music teacher. He also studied the commune and came up with many of his own ideas for a community based on individual liberties and sovereignty. The reason the New Harmony commune failed, he believed, was that it had stifled individual liberties. In Warren’s view, men should be free to do whatever they want to do, without restriction, as long as it didn’t prevent others from doing the same. (And, if you think this sounds an awful lot like anarchy, you wouldn’t be the first.)

In 1827, the Warrens opened a store in Cincinnati that he called a “Time Store”. The idea was to barter goods without any capital gains, and a theory that anything’s value should be determined solely by the amount of socially necessary labor required to produce it.

The Warrens expanded the “time store” philosophy and used it to create a new commune called Equity located roughly 180 miles northeast of Cincinnati. This “equitable village” didn’t last all that long as there was constant bickering among residents over items worth. There were also plagues of illnesses around this time that certainly didn’t help anything either. After this failed, he attempted again with a new equitable village near New Harmony, Indiana. This came with a bit more success, and in 1842 Warren opened another “time store” there.

Josiah relocated back to Ohio in 1847 where he and his wife appealed to the followers of Fourier who had first tried to commune on that land. Together, they formulated a planned society they originally called “Trialville” but later settled on “Utopia”. At first, they were quite successful. A lot of excitement was brewing on this new system where anyone could purchase and build a home, not using money but with the cost of their time and labor. This was not so much a commune (where the community-owned everything) but a society of individualists taking pride in a community they had built.

This happiness, however, did not last very long.

Why the community failed all depends on who you ask. A lot of the information we have comes from the Utopia residents at the time or their sympathizers. Some of them said that people had just moved out, as if that’s any kind of answer, without stating any of the reasons why. Others moved on to larger communities, perhaps in a better climate or next to a river that wasn’t prone to flooding.

The 1880 book History of Clermont County offers a few additional ideas. Greed may have played a major role. A contract limiting land prices expired after three years, allowing for much higher fees to be paid for purchased land, and those who owned the land around the community also raised their prices quite a bit, too, all but preventing the community from expanding.

Another factor might be the departure of Josiah Warren in 1850 to New York. His wife, Caroline, originally stuck around but soon headed back to Indiana to be closer to their son. (The warrens split but did not officially divorce. Most sources claim they remained amicable throughout their lives.)

Whatever the cause, after 1850, the population of Utopia began to decline. Today, a lot of people consider Utopia to be a ghost town, although the area is still populated with various homes and a general store still resides along US-52.

Utopia And The Ghosts Of That Underground Church

The first time I heard about Utopia it was about the ghosts roaming through the underground church. The details of the ghost story varied from telling to telling, sometimes bearing not the slightest similarity to the one before. It appears there was an underground church somewhere in Utopia. Some people say the church got flooded and a ton of people died, some of which remain to haunt the halls. Or, maybe it was a group of escaped slaves taking refuge only to be shot by slave hunters and their spirits remain for the lack of any place better to haunt. Or, perhaps the ghosts stem back from a Spiritualist Seance that had gone wrong, either killing a bunch of the people present or trapping the spirits of the loved ones the living were trying to contact.

The variety of these stories caused me to take a deeper look at the history of Utopia. I had hoped that while looking at the documented history of the place, maybe I could find something to explain all those ghost stories. A few times, I came close to finding those answers – yet, I never quite feel like I got there.

So … where did these ghost stories come from?

There is reason to believe that all three communities (The Clarmont Phalanx, Excelsior, and Utopia) had been involved in some ways with the Underground Railroad. The teachings of spiritualism, in general, and the ideals believed by most communal communities does not support the notion of slavery and many well-known spiritualists considered themselves abolitionists. However, there is little evidence from the historic record to clue us in to what Utopia’s role was in The Underground Railroad. (But, this does not mean it didn’t happen.)

It is documented that seventeen people lost their lives when the commune’s main building collapsed during the second community’s time. The problem with this theory is that it is known that structure was aboveground and located almost directly on the banks of the Ohio River, and what remains of the “underground church” sits a short ways back. There simply is no way to connect the ghost story to this structure.

I then spent a great deal of time going over all the sources I’ve gathered while researching this story trying to find some mention of a “church”. What I discovered was that none of these communities were particularly religious (some communes in the area, such as the one a mile down the road in what is today Rural, was based on Christian principles). Nowhere did I find any reference to religion, whatsoever. No churches, no priests or ministers, and the more I thought about it, the less I expected to find. It isn’t like anarchists are known for their church attendance.

The only thing that makes sense, at least to me, is that the “underground church” is actually the remains of one of the communal buildings, most likely the meeting hall and shared residences of Excelsior – the original structure that was moved in haste to the river bank.

Other than the seventeen souls that lost their life when the great hall collapsed, I haven’t found that many records of people dying in or around the utopian communities. Most of the inhabitants are said to have left on their own accord, either giving up on their dreams of communal living, or finding other communities elsewhere that would better fit their needs. All three communities were plagued by harsh weather, very basic living conditions, and all the problems associated with living next to a large river that often overflows its banks. I hardly think that any of the ghosts stuck around because they loved the place so much.

So, once again, I’m at a loss to determine what the ghost stories actually are … and where they came from.

If you happen to find yourself in Utopia, please be advised that all the property there is now privately owned, and most landowners don’t take too kindly to strangers trespassing on their land, no matter what their intentions are.

According to several websites, throughout the month of October (ok, boys and girls, can you say Halloween?) tours of the underground church are available on weekends – although without any further information, I have no idea if this is still something that goes on. I’ve also seen reports suggesting that the stairs leading down into the structure have become unstable and might have suffered some sort of collapse in the last few years – meaning the tours are now conducted above ground – if at all.

Across US-52 from the town’s general store (and west a very short bit) you will find the Utopia Historical Marker. This might be the only attraction worth stopping for.

Dig Deeper…

- Finding Utopia: Another Journey Into Lost Ohio by Randy McNull (ISBN: 978-1606351314)

- Utopia, Ohio, 1844–1847: Seedbed for Three Experiments in Communal Living – American Communal Societies Quarterly ISSN 1939-473X

- Utopia, Ohio – Wikipedia

- Digging History Ghost Town Wednesday: Utopia, Ohio

- Roadside America – Utopia, OH Underground Church