They say that somewhere in Ohio, there exists a cave that contains the bones of twenty-one escaped slaves. Legend has it that before the Civil War, the escaped slaves entered the cave, trying to hide from the slave hunters that were pursuing them. However, the cave somehow got filled with poisonous gas, suffocating them all. After their bodies were discovered, the cave was then sealed, somehow, in part to keep the gas from escaping, or maybe also to provide those lost souls with a sealed tomb.

History and Legend

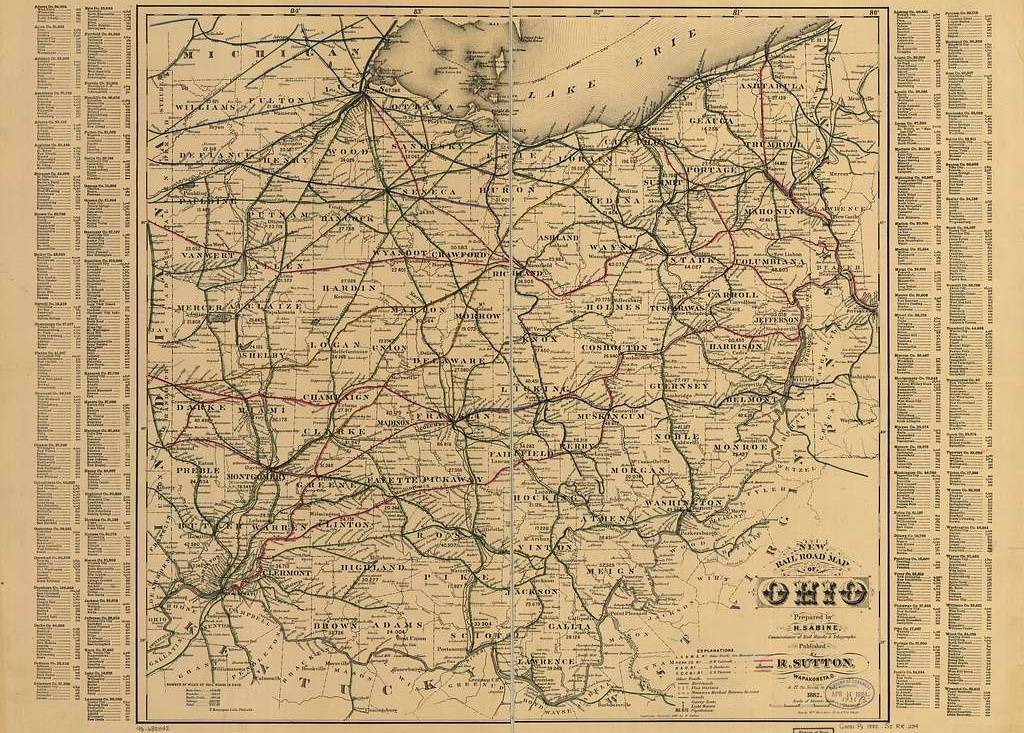

The root of this story appears to be an article from the Middletown newspaper printed in 1892. The article was written by a man named John, who said the cave was somewhere on his family’s land, about six miles from Middletown, Ohio.

According to the article, in 1842, a group of escaped slaves was hiding in the house of a Middletown physician ten miles south of Middletown. The doctor became alarmed after hearing about a group of slave hunters in the area who were searching for these slaves. He rounded them up in two wagons and drove them away in the dead of night, following a small road along Elk Creek until they came to the cave. It was a small, cramped space, but he was certain they would be safe, for now.

The physician then knocked on the door of John’s (the article writer) father, an abolitionist sympathizer. John’s Father tells the doctor that he knows about the cave and calls it a deathtrap. He also mentions that a group of geologists from the “Department of Washington City, D. C.” had visited the cave a few years prior, but had never returned.

At some point later, John’s Father returned to the cave and discovered the bones of dead men, vowing never to return to the cave ever again. Before he left, he sealed the cave, somehow.

The story surfaced again in the 1980s when a historian from Middletown discovered the old newspaper story and wrote his own article for the Middletown paper. This article seems to have inspired many historians, spelunkers, and other interested parties to look for the cave and see if they could find anything that survived the test of time.

In 1997, Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center sent Historical Researcher Mary Ann Olding to the area, although after several days of work, they were unable to find the cave or any further information about its location. After this, several authors and historians looked into the story – but it doesn’t seem as if any new information could be uncovered.

The big question is – Is John’s story true? Or, was it something he just made up for some reason?

In the 1800s, Middletown, Ohio was home to a large community of Quakers (Religious Society of Friends). It’s not important to go into their religious or spiritual teachings, but it is important to know that they were strongly against the idea of slavery and played a major role in the history of the abolition movement. And, many Quakers became involved with The Underground Railroad, becoming “conductors” or providing safe houses.

To be fair, John’s story does not mention if he, his father, or the unnamed physician were Quakers, however considering the number of Quakers in the area at the time, it is entirely possible.

John’s Story – Fact or Fiction?

On the surface, John’s Story is entirely possible. However, it contains little in terms of verifiable details. Considering the time the piece was written, however, that’s almost to be expected. The Underground Railroad had to operate in secrecy if it was going to be successful. The last thing they wanted was for the names or locations of stops from being known. Had John written that Doctor Yuri Zhivago, who lived on this particular street and spoke with a Russian accent, was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, that would have been the first place people started looking, thus rendering his stop ineffective. And it just might put him, and his life, in jeopardy.

Another thing worth noting is that the first article was written in 1892, but the events it describes take place fifty years earlier in 1842, and the events happened to his father, not him. We do not know who John is, so we can’t even begin to guess his age, but chances are he either hadn’t been born yet in 1842, or he was a young child. It’s entirely possible that everything John wrote were things he believed to be completely true, because that’s what his father said to him.

There is no way of knowing if John’s father made the story up, or if some of the details weren’t quite right. And if his father did change a few details, for example – if it wasn’t a doctor that lived ten miles south of town, but one who lived west of town, or maybe he wasn’t a doctor, but some other profession – it could have been an attempt to keep the identity of the underground railroad conductor safe, as opposed to any sort of nefarious deceptions.

John’s story does have just enough details that it could be possible. At the same time, it doesn’t have enough details to prove or disprove either way.

There is, however, one element of the story that does not hold up. John’s Father mentioned a group from the “Department of Washington City, D. C.” having visited the cave and was never seen again. Obviously, there is no Department of Washington City, D.C., however, that could have been how John’s Father referred to the federal government at the time. Still, that detail seems a bit off.

Many people have tried to interpret this as being the United States Geological Survey. The problem with this theory is that the group was not formed until March 3, 1879, well after the escaped slaves were supposed to have died in the cave. At that time in history, there was no governmental agency handling geological surveys. Both houses of Congress did, at the time, occasionally commission surveys, such as when establishing state boundaries. There is no evidence that any federal surveys had been commissioned in the area at the time. It’s also unlikely they would have claimed to be from “Washington D.C.” so the likelihood of this happening are extremely thin.

More recent geological surveys have cast doubt on whether or not caves exist along the Elk River, or even in Butler County in general. Most found that the appearance of caves was highly unlikely, although still possible, as sinkholes do happen from time to time, and occasionally previously unknown caves are discovered.

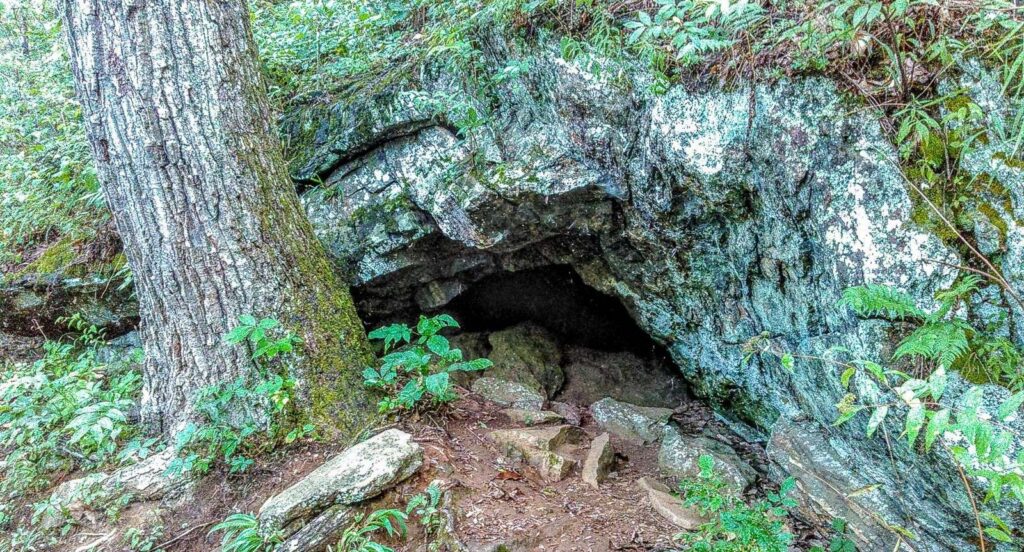

One geologist believes the escaped slaves entered not a cave, but some sort of “joint” or crack in the rocks, and not a legitimate cave, per se. These cracks are often cave-like in general appearance, leading some to speculate this is what happened with John’s father.

Another element of this story that has faced scrutiny is the idea that the cave got so filled with natural gas that everyone who ventured inside died. That would be a very rare occurrence, but somehow still within the realm of possibility. Even though the local ecology doesn’t support the best conditions for this to happen, a number of well drillers have discovered pockets of natural gas.

Or, maybe there is another explanation. If the cave or “joint” was small, there wouldn’t have been a lot of space for a small group of people. If the escaped slaves feared getting caught by Slave Hunters, they may have taken steps to hide or cover the cave opening. This would have blocked their access to fresh air, and if the cave were small enough, it wouldn’t have taken long for the cave to be filled with carbon dioxide. Without fresh air, it wouldn’t take long for them to fall unconscious and ultimately die.

Notes From The Underground Railroad

Let’s assume for a moment that this story is true, at least in its most basic form: A group of escaped slaves made their way along the Underground Railroad into Ohio and hid in a cave of some sort when their pursuers got close, only to die in that cave. After they were discovered, the owner of the property sealed up the cave somewhere, and now nobody knows where it is, exactly. If that really happened, its historical significance would become clear.

Whenever we study any aspect of history, we always need to look at where our information is coming from on multiple levels. In this case, the story was told many years after it happened, and it was told by someone who was only indirectly involved. This, in and of itself, does not invalidate the story, but we cannot consider it to be undeniable proof, either. At this point in time, we know next to nothing about the runaway slaves, the local physician, or the man who owned the property the cave was located on (who was probably the father of the person who told the story.)

From the story itself, it’s assumed that both the cave property owner as well as the physician were abolitionists. This clue is not going to get us any closer to their identities (let’s just say that abolitionism wasn’t exactly rare in southern Ohio) it may give us a little insight into the story.

While the Underground Railroad was in operation, it was imperative that it operate in complete and total secrecy. In other words, nothing was ever documented. It wasn’t like a conductor could hang a sign outside his house saying runaway slaves would be safe here – as soon as the slave hunters saw that, it would soon become the first place they would look. Nor did the conductors create any lists of who they helped and how – if that information got into the wrong hands, it could prove to be devastating not only for themselves but also for those they were trying to protect. Likewise, pro-slavery activists and slave hunters didn’t keep good records, either. The last thing they wanted was for the abolitionists to know what they were up to for fear they could use that information to move slaves to a different location. They also didn’t want other slave hunters to collect the bounties on the escaped slaves they were after.

Therefore, during the times the Underground Railroad was in operation, any records at all are immediately suspect.

After slavery was abolished around 1865, some things were slow to change. Just because the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was suddenly a thing, that did not mean that some people were all that happy about it. Nor did it mean that former slave owners were content to just sit back and accept that what had once been their property (aka slaves) was now free. And this should go without saying, but it wasn’t as if former slaves (or those who looked like them … i.e. anyone with black skin) were now accepted and welcomed in America.

For the abolitionists, the 13th Amendment was clearly a success, but they were under no illusion that the fight was anywhere near over, and The Underground Railroad continued to operate, just perhaps a bit differently than it had before.

By the time the Underground Railroad was finally no longer needed as much, anyone saying they were involved with any aspect of the Underground Railroad was, at least in some circumstances, seen as an almost glorious thing. It was one thing to say you supported the movement, it was something else to say that you (or your family) actually helped, perhaps risking their own lives and safety. And, owing to the nature of the Underground Railroad, there was little proof one way or another – it’s sometimes a bit hard to tell who’s telling the truth and who’s uttering pure porkies.

When discussing the cave at the heart of this story, the one question I seem to hear more than any other is why the author of the article, the son of the farmer who owned the land the cave on, the friend of the physician who operated as an Underground Railroad conductor … why would he lie? Well, there is, unfortunately, a pretty big reason right there. Is it possible that John, the author of the original article, wrote the piece to make himself or his family seem better than they actually had been? Or, is it possible that John’s father lied to him about the existence of the cave or the human remains it contained? Or, is it possible that John had misunderstood what his father had told him, filling in some of the blanks with facts he thought (or wanted to be) true?

Sadly, yes, all those things are somewhere within the realm of possibility. But, on its own, that doesn’t mean the story isn’t probable. All it means is that more information is needed. And, sadly, the only reliable place to get information today would be if the cave and the remains were found.

If any part of this story were true, it would be an invaluable piece of tangible history relating to The Underground Railroad. And, anything that can shine any new light on this period of history has to be a good thing.

What If The Story Isn’t True

Let’s assume that this story isn’t true. There is no cave in Ohio with the remains of escaped slaves. Maybe John lied when he wrote the article … maybe his father lied to him … maybe the author didn’t understand what had happened and wrote about things he thought were true but weren’t. I’m not trying to lay any blame here, I just want to ask if this story still matters…?

There is something about this story … a hidden cave … runaway slaves on The Underground Railroad … human remains buried in unmarked graves … there’s something about all this that just captures the imagination. On several occasions, historians, geologists, and a few adventure seekers have studied the region and tried to locate the cave. These events, when publicized, not only alerts some people to a period of history they might not otherwise have shown an interest in (which is arguably good), it benefited the local economy (people wanted to come to the area to see things for themselves), and it can also be argued that it helped the advancement of science, using new technologies to try and solve old mysteries.

Even if the facts of the case prove to be untrue, for whatever reason, just looking at the story can allow us to view how things were in the times of The Underground Railroad.

Therefore … to me, at least, if the story is true or untrue … it matters. And it will continue to matter until the mystery is solved, one way or another.