When I was reading the story of Thomas D. Carr, what struck me the most was the idea that if these events were to have played out today, as opposed to 1869, things would have been played out very differently. Then again, that can be said about a lot of nineteenth century events.

Louisa Fox & Family

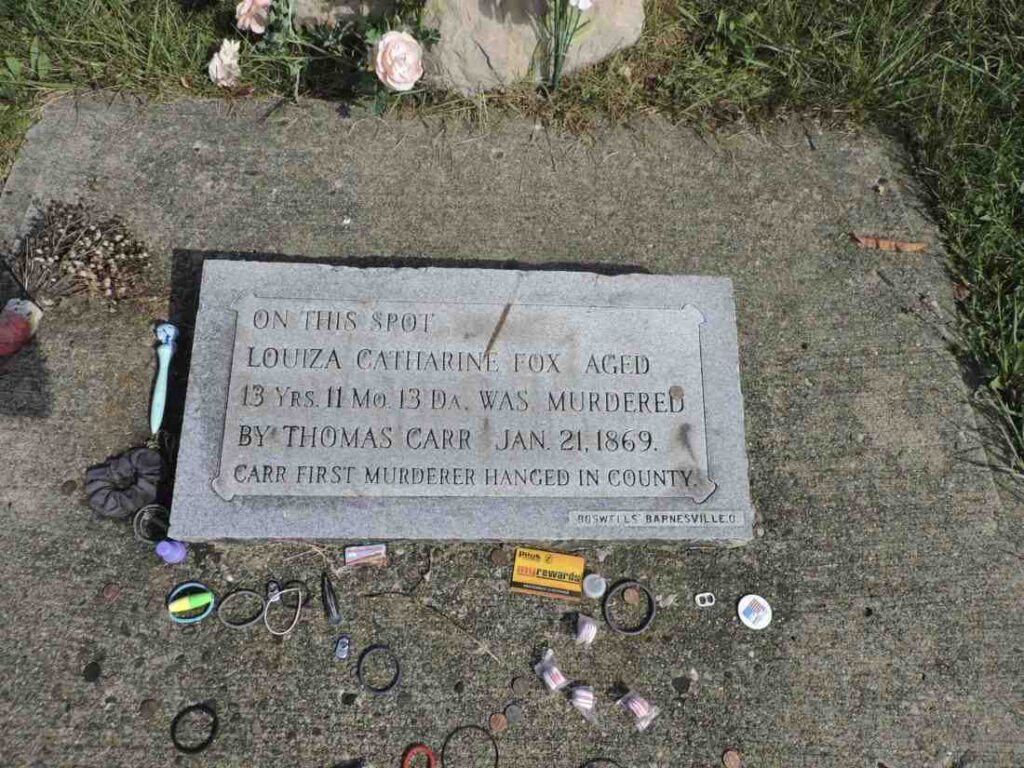

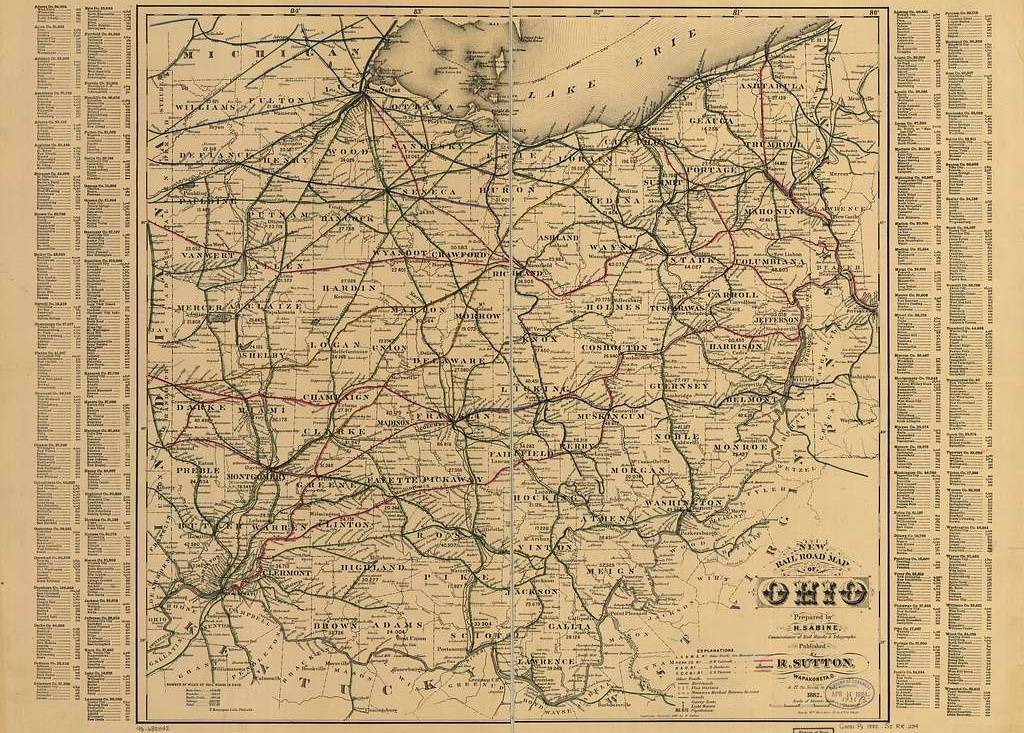

This story starts (or, I guess it ends) with Louisa Fox. She’s thirteen years old and living in an unincorporated area called Sewellsville in Belmont County, Ohio. Today, this area is in The Little Egypt Wildlife Area, a popular spot for hiking, fishing, and camping, but back then it was known for its surface mines.

Louisa worked for a man named Alex Hunter (because child labor laws weren’t a thing yet) who owned the local Mine. It was most likely there that Louisa met Thomas Carr, who had recently come to town and was working at Alex’s mine. No matter how they met, Thomas became infatuated with little Louisa and tried spending a bit of time with her. At first, she seemed to accept his attention, however she quickly realized he wanted more than she wanted so she put a stop to it.

That wasn’t the end of it, though, because Thomas had already decided that Louisa was to be his wife because he was in love.

Being that this was the 1860’s, it wasn’t uncommon for fathers to marry off their daughters at an early age, even as young as thirteen. However, Louise’s father did have some reservations, including some reservations about age. Not his daughter’s age, mind you – but Thomas … a twenty-five-year-old Army veteran from the 18th Ohio Infantry Regiment. He was (almost) twice her age.

Their big problem, however, was that he could be a bit of an asshole, especially when he’d been drinking, which he did nearly every night. Then again so did a lot of men his age, considering there wasn’t much to do otherwise, and those miners had to do something to take their minds off work for at least a few hours every night.

We’re not entirely sure what exactly caused Louisa’s father to put his foot down and say there would be no marriage, but that time had finally arrived. And considering that no thirteen year old girl could get married without her father’s consent, this should have been the end of it.

Jan 21, 1869

On the evening of January 21, 1869, Thomas Carr was beyond mad. He was furious. Earlier in the day, he had tried once again to convince Louisa’s father to allow him to marry her, and again the father said no. This time he says it a little bit differently: It’s never going to happen, please stop asking, you’re being an asshole please leave us alone. (Those weren’t the exact words her father used, but I’m sure I’m not wildly off.) Then Louisa’s father gives Thomas some devastating news. Louisa’s going to go stay with her grandmother, somewhere far away, where Thomas will never find her, for a while, or at least until Thomas gives up for good and moves on with his life.

Thomas isn’t going to let that happen.

That evening, he hides behind a large oak tree waiting for Louisa and when she and her brother, Willie, get close, he jumps out and tries to talk to her. He tells Willie to head home so the two of them can talk. Once the boy had walked off, Thomas tells Louisa that her father finally agreed that the two of them could get married, but she saw through the lie and again refused his advances. She, too, makes it pretty clear that she wants nothing to do with him anymore.

While they’re talking, he is dominating her and refusing to allow her to leave. He’s also downing hard cider so it’s fair to say he’s pretty drunk at this point. He’s tried everything to be with the girl he thinks he loves, but he’s got one play left. He starts to blame her for this mess, because if she wanted to be with him as much as he loved her, none of this would be happening. Then he drops the final bomb on her.

He says she has two options, run away with him and live in happy bliss, or die. And she has no desire to go anywhere with him, so she says she chooses death.

What she didn’t know at the time was that earlier in the day, he had stolen a razor blade from Alexander Williams’ shoe store. This he then uses to slash her throat across the jugular vein, leaving a gash about ten inches long. As if that wouldn’t have killed her, he then continued to slash her over a dozen more times, mostly to her neck but also her hands and breasts.

When he was done, he started to walk up the hill and was contemplating suicide when he got a better idea. He’s going to go into town, somehow obtain a gun, and use that to shoot the wife of Louisa’s boss, Mrs. Hunter. Then, maybe, he’ll use it to kill Louisa’s father. He does make it to a few houses asking to borrow a gun so he can kill some rabbits, and finally someone does.

Before he could reach his target, his path took him by the crime scene and to his surprise there were quite a few people there. As it turns out, Willie walked away from his sister, but stopped and watched from a distance until Thomas pulled out the razor and it was at this point that Willie finally ran home and alerted his father to what he had seen.

When the crowd spotted Thomas, someone pointed to him and screamed “Murderer!” which caused the group to turn toward him. Now Thomas has a gun, which he threatened to use, which gave him a few seconds head start to run away. Somehow, he managed to elude the group.

Thomas had another problem. He had not eaten anything that evening, plus he had been drinking heavily. Needless to say, that made him even more tired than he should have been and made him more susceptible to the effects of alcohol. So, him illuding the posse trying to track him down was quite the achievement.

Thomas winds up behind the Fox family home and was able to spy Louisa’s body which had been laid out on the kitchen table. He wanted so badly to go into the house and give her one last kiss (and maybe do who knows what to her corpse because at this point I don’t think anything is off the table for him), but there were too many people in the house. And it’s late, and he’s drunk and tired, so he finds a coal bank he’s relatively sure is a good hiding place, which is where he woke up the following morning.

The Next Day

After waking up, Thomas Carr really wanted to return to the Fox house to check on the girl he loved, but there were too many people around. He also started to realize that life as he knew it was over, so he retreated to a hiding spot he felt safe enough in and tried to take his own life.

Thomas rigged the gun he had “borrowed” with a straw hat and a handkerchief, but when it was time to do the deed, he jerked his hand and instead of shooting himself in the head, he hit his chest, missing all his vital organs. Then he tried to find the bullet, but failed at that, too.

While he contemplated what to do next, he left his hiding spot to get a drink of water from a nearby well, which is when he was spotted by some people who were looking for him. Not wanting to get caught but seeing no other alternative, he returned to his hiding spot, pulled out the razor blade he had used to kill Louisa and tried to slit his own throat.

I say tried because all he did was stab himself in the neck, nearly severing his windpipe.

Finally, his world went dark as he drifted from consciousness…

Would You Believe This Story Is Far From Over?

Stabbing himself in the throat didn’t kill Thomas Carr either – it just caused him to pass out. So, once he was caught, he was nursed back to health because if they’re going to hang him, he’d better be in the best of health.

One other thing was clear – this trial was going to be a big deal. It was reported in all the nearby local papers, the Fox family was so loved by the community, and the details about the murder painted a picture with such depravity, how could it not be the talk of the town?

The defense tried to claim insanity. They produced a doctor who gave testimony that certain behaviors Thomas displayed before the murder were clearly those of an insane person. The problem was that the doctor did not testify about any of his behaviors the day of, or the day after the murder. They assumed that if they could point out that Carr was insane before the murder, then clearly, he was during as well. For some reason, though, this idea was never presented directly to the jury and there was no instruction on whether they could consider that or not.

Thomas Carr was, of course, due to the overwhelming amount of evidence against him – found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Carr’s attorney appealed. It wasn’t fair, Carr’s attorney claimed, that the jury didn’t know if they could find the guy not guilty by reason of insanity based on his previous action and diagnosis. His execution was put on hold temporarily as the judge reviewed this claim. Ultimately, he would rule in the prosecution’s favor, saying it didn’t matter. The vicious and brutal murder of an innocent child was so egregious, the only outcome should be at the end of a rope.

His new execution date would be …

Mar 24, 1870

On the morning of his execution, Thomas Carr was informed that, even though he was about to die, he had a couple of visitors. Two young ladies, to be exact, wanted to meet him. He spent a little time with them both, gave them some of his jewelry to remember him by as well as a photograph, and told them he would see them in heaven.

Thomas Carr was, it seems, ready to die.

As workers finished putting together the contraption that would end his life, he offered to help out, even danced on the platform to the dismay of everyone. As the time drew near, he announced he wanted to make a statement. He confessed to having murdered Louisa, which was no surprise. What was surprising, though, he tried to shift the blame to liquor.

“The bitter cup they call whisky has brought me here. It will ruin any man. Whisky, whisky is what brought me where I now stand – a condemned murderer, about to be launched into eternity. Oh, take my advise, and banish it. – Banish whisky, and you banish crime. Look at your prisons, look at your poor, look at the gallows erected here to hang me – a soldier who fought five years to defend the Government. Keep liquor away from your citizens; banish whisky, and you will have no more wicked men like Tom Carr to execute. I pray earnestly that God will break up the dram shops. Pray for it, every one.”

Thomas then went on to tell his life story, about his abusive father and how the family had to move around before he could form any lasting friendships. He spoke of getting into street fights with other boys around his age and how as a child he spent time in prison. He talked about how he and two other guys, John H. Burns and Oscar Myers (not the food dude) kill a woman named Mary Montoine. He claimed that he joined the 16th Ohio Infantry by lying about his age, after which he was often cited for misconduct, once even being forced to dig his own grave after military leaders tried to scare some decency into him.

The confession also consisted of several other murders among other crimes such as robbery.

After he had finished confessing his multitude of sins, he was duly hanged and not taken down until he was dead.

Some Mystery Remains

The evening papers from all over the region began that evening to report on the details of Carr’s confession. And from the start, people began to notice that things weren’t exactly what they seemed.

One editorial blasted the confession as lacking verifiable details, another would ask if it were even possible that one person was able to do all the things he claimed without getting caught.

And then the fact checking began and the results were … well, a bit confusing.

Some of the details just didn’t add up.

For example, Carr detailed how he helped police track down John H. Burns who had gone into hiding after the murder. The problem with this was that Burns had not gone into hiding and was arrested by police who went to look for him at his job.

He also had claimed to have helped kill German traveler by the name of Aloys Ulrich by bashing his head in with a rock. However, Ulrich suffered no head injury other than the fatal wound inflicted by a hatchet carried out by his traveling companion, Joseph Eisele.

Without enough details as to time and place or other details that could help confirm Carr’s claims, people started to wonder if he had, in fact, done any of them. (Except for killing Louisa Fox, since all the evidence pointed to him, and her murder was witnessed by her brother.)

No one could understand why he would lie. Or, if he wasn’t lying, why did he get so many things wrong and leave everything else vague.

True Crime – Then vs. Now

As I said in the opening paragraph of this post, had these events started to play out today, things would have ended very differently. The most obvious reason I say this is because times have changed and what was once acceptable (at least to some degree) isn’t now. Today, if a grown guy approached another man and said he wanted to marry his thirteen-year-old daughter, that would have been the end of the story. Either the father would have grabbed a shotgun and changed the man from a rooster to a hen (as Queen Dolly said in 9-to-5) or the cops would have been called and the guy would have been beaten to death a few days later in a prison cell because even convicts can’t stand being around a child predator like that.

These events also point out how labor laws (especially child labor) have changed as well. Today, no thirteen year old would have a full-time job, especially if it were something like being a housekeeper (or servant) to another family. Sure, a kid might spend a few hours babysitting their toddler some number of days per week, but that is a long way off from being a family’s servant.

The biggest difference between then and now, I think, is that we know a lot more about crime today. Modern psychology has come a long way in understanding why criminals do what they do and what can be done about it. Likewise, thanks to (seemingly endless) press coverage, and it being the subject of so many television shows and movies, it’s easy for us to think we can understand most of what there is to know. (Yeah, I’m not mentioning true crime bloggers for what should be some fairly obvious reasons, but frankly I’m not because it really doesn’t matter.)

When Carr initially confessed to all his crimes, people wanted to accept it because it fit the narrative of the time. They knew he was guilty of one murder (Louisa Fox) so if he says he killed (or helped kill) these other dozen people … well, they were certainly glad that such an evil man was about to hang for his crimes. Surely, the reason he confessed was because he knew he was about to die and confession is good for the soul, right?

It really is hard to understand what people were thinking back then, although we do have newspaper reports, journal or diary entries, among other sources that do give us some insight. However, this story takes place a long time before most of the events that helped shape the modern paradigm of all things true crime. Heck, it was even over a century before Jack the Ripper killed a few people over in London and we’re still not entirely sure we know who he really was or why he did what he did.

We now know there are a multitude of reasons someone may confess to crimes they didn’t commit … or give misleading statements in their (so called) confessions. Like…

Intellectual or Mental Defects – If I may be blunt here (and I mean no disrespect) some people confess to crimes because they do not have the mental capacity to fully understand what they are really doing. This can be due to either some kind of mental illness or because of diminished intellectual abilities. I’m not trying to suggest that it’s perfectly normal for anyone with Special Needs to start confessing to murders, but there are quite a few cases where this sort of thing does tend to happen.

Seeking Notoriety – Today we know that sometimes a person will go to any length for a bit of attention (and we have multiple industries based on this fact alone, such as “reality” television, the world of “Influencers” and “internet celebrities”. Even in our daily lives I think we know someone who either exaggerates stories for some personal benefit or who completely makes up stories just for the attention. And yes, sometimes people really do say they committed major crimes, even murder, because they crave attention or notoriety.

Deceptive or Manipulative Policing – This has been (and probably always will be) a controversial subject – police lying to a subject in order to obtain a confession. And, within reason, this tends to be a mostly acceptable tactic. For example, a police officer may lie to a prostitute (“No, I’m not a cop!”) when trying to get her (or him, I don’t judge) to offer services for cash. Courts have ruled that it is fair and is in no way considered entrapment. The problem is, though, that this is fairly easy to abuse. There have been cases where people have confessed to crimes they didn’t commit because they did not think they had any other options or because the police lied about what would happen after they confessed.

Heuristics and The Fundamental Attribution Error – The human brain can sometimes make decisions or solve problems with little thought (a process known as heuristic) which can be a good thing. (OMG, your house is on fire, you have mere seconds before you either burn alive or pass out from smoke fumes, so what do you do? Do you act as if on instinct or do you sit down and weigh all the pros and cons of every decision you can make? No, you make a series of decisions at the moment that somehow save your life.) Although sometimes these decisions can be bad. (You’re tired and hungry and desperately crave caffeine or a cigarette and you’re lulled into confessing something even though you did not consider all the possibilities – this is the Fundamental Attribution Error.)

Frustration Tolerance and Conflict Avoidance – If you’ve ever gotten frustrated and done something you wouldn’t normally do just to get yourself out of a situation then you might have a low frustration tolerance. And some of us will do anything (like, I don’t know, confess to murder) if it gets us away from any kind of conflict. Frankly, it’s easy for us to sit in our living rooms drinking our wine coffee whatever and say we would never do that, but unless we find ourselves in that situation, we really don’t know how we’d react.

There are a number of other reasons people seem to confess to things they didn’t do, but I am going to stop there. We need to get back to Thomas Carr.

The Unsolved Mysteries (not the TV show)

We know Thomas Carr confessed to a bunch of crimes right before his execution by hanging. And that leaves us with a little mystery to solve.

Did he actually commit all those crimes? We actually know the answer to that – no, he didn’t. There were a few things in his confession that we now know he lied about. So that raises the next question (and it’s a bit harder to answer): Did he commit any of them?

It would be easy for us to say that since we know he was lying about a couple of them, then he was lying about the rest. But that would be an assumption on our part and that’s not good enough.

Many of the details he gave were just too vague to draw any conclusions on. For example, he claimed that while he was serving in the Army, he left the base for a bit to drink some of that devil’s juice (alcohol) when he was confronted by a citizen accusing him of desertion. To end the argument, Carr pulled out his gun and shot the citizen in the breast then ran away before anyone could see him. However, without a date or time or actual location, it’s damn near impossible to tell if this actually happened or not. Is it possible this happened? Maybe. However, one would think there would be some kind of record somewhere. A gun going off near an Army base would draw some attention, and a recently diseased (clearly killed by another) citizen being discovered would likely have been officially reported somewhere, too. Yet, none of those records seem to exist.

If Thomas Carr lied about the things detailed in his confession, the question that remains is … Why? There is no obvious reason (even in retrospect) for him to lie, nor is there anything that benefitted him in the slightest. He voluntarily made his statement without any coersion from anybody. He had been in custody for long past the time it would have taken him to sober up, so unless guards were supplying him with booze, any kind of intoxication is out, too.

I do have a few theories, though.

There may have been some kind of mental illness going on. Yes, he was frequently drunk, and those who consume that much alcohol can sometimes be assholes, but that’s also a sign of mental illness or psychological instability. We don’t have nearly the data we would need for any kind of diagnosis (which would be inappropriate anyway) however depression, PTSD, and borderline personality are possibilities along with more severe forms of psychosis.

Another theory is he confessed to crimes he didn’t commit for attention. I was immediately going to dismiss this theory, except for one small detail. On the day of his execution, when he was already set to get lots of attention, he met with two young ladies who had become smitten with him during his trial. (I guess some girls really do love them bad boys.) He seemed to relish that attention, giving them gifts and promising to see them in heaven. Therefore, maybe he was seeking some attention. Or maybe because he knew he was going to die (which is what he wanted) he thought that by giving such a dramatic confession, he thought he would be remembered more than he would have without it.

One final theory goes off in a completely new direction.

There are quite a few fictional stories (movies, TV shows, books, etc.) where a character confesses to crimes they didn’t commit because they are trying to protect someone. This is usually because the police suspect the person they are trying to protect is guilty and by confessing they are protecting them from prison or the death penalty or whatever (and bonus points if the confessor is terminally ill, which happens more than you would expect). In these stories, it’s often presented as either a noble action, or as a device to set up a plot twist. This situation does happen (but not nearly as frequently as it does in the movies.)

I don’t believe that Carr was trying to protect anybody like this, but I do think it’s possible that if he was friends with these people (such as John H. Burns) he may have thought that by confessing, maybe his friend’s punishment would be a bit less. Or maybe he felt that the other person

This of course does not explain all the vague details he confessed to, but it still may be a factor in the greater story.

It’s also entirely possible that he was guilty of the vague crimes he confessed to. Several researchers have tried to investigate this matter and so far have come up without any answers. But, who knows, maybe at some point in the future we can find a way to know for sure.