The year is 1863. The place is not Ohio, but Hamburg, Germany. This is where we first meet Professor Otto Lidenbrock and discover that he’s just found an ancient manuscript written in some kind of Runic Script by some nearly forgotten alchemist, Ana Saknussemm. Once translated, it tells of a vast subterranean world.

Before long, he and his nephew Alex travel from Germany to Denmark, then Iceland where they hire Hanz as a hunter and tour guide. They ultimately arrive in Snæfellsjökull where they enter a cave and experience some weird phenomena. Just when they’re almost out of water they find this vast underground river, then one of their group gets lost after a landslide, then these dinosaur-like creatures show up and after an epic adventure they get spit out of the earth through another volcano, Stromboli, in Sicily.

This is the plot of the French novel Voyage au centre de la Terre, which thankfully changed when it was translated into English as “Journey to the Center of the Earth”. And I do apologize if I butchered the general plotline of the novel, but really, Jules Verne’s masterpiece should be experienced for oneself.

This Verne masterpiece has been thrilling bored school children since it’s initial publication in 1864 (although it was revised a few years later, in 1867 before being translated into English in 1871. The basic idea was that there was a vast underground world inside the Earth where strange things happen and supposedly this is why Volcanoes exist, or something.

If you’re wondering where Jules Verne got the idea for his little novel and what this has to do with Ohio – the answer to that is fairly simple: He got his idea from John Cleves Symmes Jr., Ohio resident and nephew of Ohio’s early pioneer, John Cleves Symmes.

Who Was John Cleves Symmes Jr.?

John Cleves Symmes Jr. Was born on November 5, 1780, in Sussex County, New Jersey to Thomas and Mercy Symmes who named him after his famous uncle (who was a delegate to the Constitutional Congress, a Chief Justice of New Jersey, and he was US President William Henry Harrison’s father-in-law as well as an early Pioneer of The Northwest Territory who (among other things) purchased a bunch of land he helped develop in and around what is now Cincinnati.

Yeah, I know it’s confusing when two people in history share the same name, but it’s too late to force one of them to change now, isn’t it?

Junior was commissioned into the 1st Infantry Regiment where he gradually was promoted through the ranks. During the War of 1812 he was stationed in the Missouri Territory until his unit was sent to Canada in 1814 where they helped in the Battle of Lundy’s Lane before joining the Siege of Fort Erie. He would be discharged from the Army on June 15, 1815.

While he was in the Army, he got into a duel with a fellow Lieutenant named Marshall, and while both men walked away with minor wounds, the two men became the best of friends. The following year he married a widow, Mary Anne Lockwood, who had six kids of her own before they started adding to that number.

After his Army career was done, he returned to the Missouri Territory and tried his hand at trading before declaring himself an ultimate failure before moving to Kentucky, where he tried (and failed) again. Finally, he moved to Ohio where he seems to have taken up the hobby of contemplating things.

It was while he was contemplating the Rings of Saturn that he developed his own theory – and by that, I mean … he took a theory that had been debated (and rejected) for a long time but put his own spin on it. To some people, he became The “Newton of the West” … but, to everyone else he was just another idiot.

Symmes’ Hollow Earth Theory

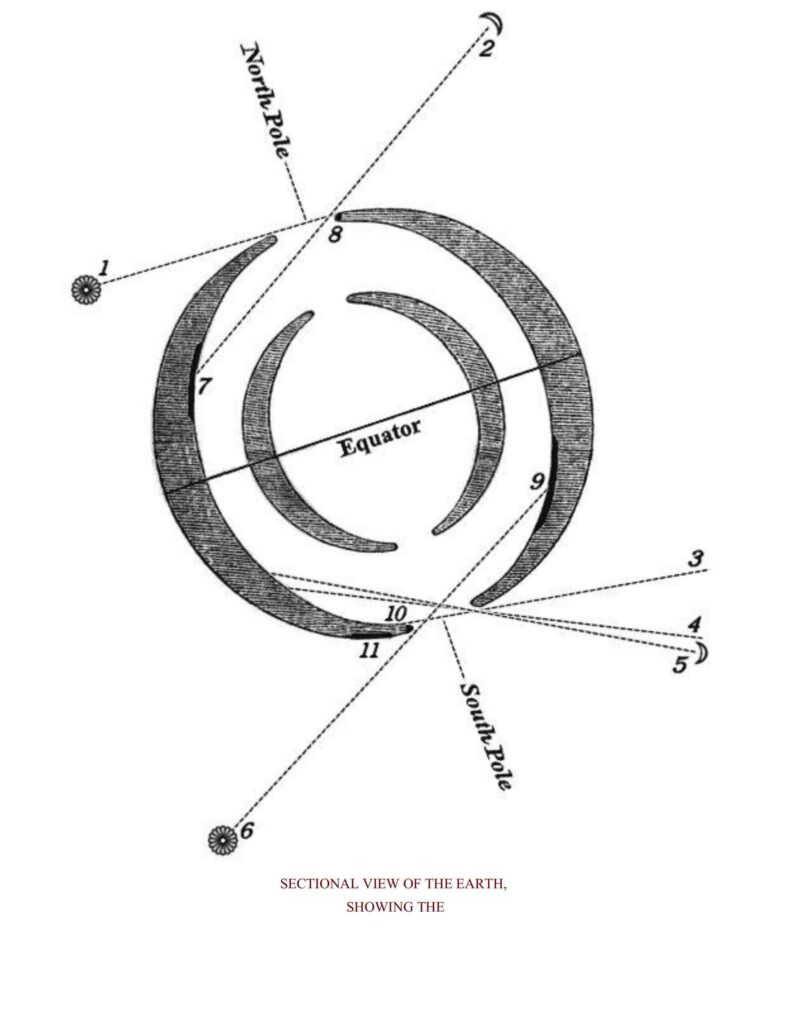

The Earth, just like every planet in the solar system, said Symmes, was Hollow. The Earth we knew was just an outer shell. Inside the earth, he said, you would find a series of five solid concentric spheres (although he would later change his theory to be just one). Our outer layer was about a thousand miles thick. At both the North and South Poles, there was a hole (later referred by history as Symmes Hole) about six thousand miles wide that would allow someone to reach the next layer down. The hole was so large, he believed, that you could make your way into this lower level without even being aware of any transition.

Each of the inner spheres would spin on its own axis, which is how he explained the instability of magnetic north.

The inner spheres would be illuminated by light reflecting off the outer surface of the sphere one level lower, which would appear as some sort of aurora.

This would create an ideal place for all sorts of plant and animal life, and he surmised that also would include human life.

When Symmes first published his theory, there were some things that were new (such as the openings which could allow people to explore the inner levels) however some version of a Hollow Earth Theory had been around for quite some time. In fact, explorer (and dude they named a comet after) Edmond Halley had published his theory all the way back in 1692. It is worth noting, however, that Halley’s Hollow Earth Theory and Symmes’ Hollow Earth Theory may be similar in tone, but many of the details were vastly different.

The Things We (Used To) Believe

Today, we may role our eyes at those who believe the world is flat. This is not because we live in Ohio and therefore know, beyond any shadow of any doubt, that the world is, in fact, quite hilly – but because we know better. We might be tempted to do this, too, to those who believe that the Earth is hollow, but we also must remember Symms lived in the nineteenth century and Science has changed a bit since then.

At the time, the theory that the earth was hollow wasn’t as farfetched as it would be today. Modern advances in the sciences help us explain natural phenomena that they were just barely aware of at the time, including things like why really old animal or dinosaur bones were being discovered under the dirt or why which way the compass called “North” wasn’t always in the exact same place.

Even at the time when Symmes was going around and speaking about his Hollow Earth theory, most people thought there were too many things that didn’t make sense. Yet, there was little known at the time that could prove Symmes wrong.

As far as being a public speaker, Symmes wasn’t the best. Actually, at the time he was considered among the worst. He was still able to draw large crowds, though, and even managed to “convert” some people to his beliefs. It did not take long for him to begin gathering support for an “Artic Voyage” in hopes to find his Symmes Hole and prove to the world that it was hollow.

Sadly, this voyage never took place, in spite of all the interest there was about it. What we got instead was … something else. A book of fiction called Symzonia; Voyage of Discovery which … well, we’re not sure who wrote it (some say Symmes wrote it himself but others have made different claims and the bottom line is we actually have no idea) but it does present Symmes Hollow Earth Theory, with diagrams, and tells a story of what such a voyage could have been like … or, at least could have been right had the earth been, in fact, hollow.

The Symmes (Junior) Legacy

John Cleves Symmes Jr. died on May 28, 1829, at the ripe old age of 48. Other than leaving behind a widow with three kids to raise, he also left a series of unpublished manuscripts and a mountain of debt. Suddenly, it fell to his 17-year-old son Americus Symmes to provide for his family and clear up his father’s debts.

John Symmes Jr published eight pamphlets starting with his “Circular No. 1” – that laid out the basics for his original Hollow Earth Theory. He would go on to publish seven more, but it was one published in 1819 entitled Light Between the Spheres that gained the most notoriety after it was published in The National Intelligence. (That’s not to mean that it was well received though as that paper did get quite a bit of criticism, if not downright scorn.)

Much of what remains of his ideas come from two separate works, both written by his friends and followers: Symmes’ Theory of Concentric Spheres by James McBride and Remarks of Symmes’ Theory Which Appeared in the American Quarterly Review by Jeremiah N. Reynolds. Throughout this time, there were others who published criticisms of Symmes’ theories, or came up with their own, such as W.F. Lyons’ The Hollow Globe, however it didn’t mention Symmes at all.

Americus Symmes felt that some of the criticisms his father was getting, especially after his death, either was not fair at best, or misleading mischaracterizations at worst, so he went on to publish The Symmes’ Theory of Concentric Spheres from unpublished works and notes his father had written, which he hoped would help set the record straight.

Symmes was buried in the Pioneer Cemetery of Hamilton, Ohio. However, when the cemetery was decommissioned, nearly all the bodies were relocated to the new Greenwood Cemetery north of Hamilton, however Symmes remained. A short time later, Americus raised the funds (and got permission) to erect a monument to his father and his theory in the North Ward Park (now called Symmes Park) which is where his monument stands today.