What was the Best-Selling novel of the Nineteenth Century?

Gosh, I hear you say – there are so many wonderful books to choose from. You’ve got a number of Jane Austin novels to choose from, or perhaps something from the Brontë sisters. There was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, and works by Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins, George Elliot, Charles Dickens, H.G. Wells, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Oscar Wilde, Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson, or L Frank Baum, just to name a few.

Would it surprise you to learn that the second best-selling book of the 19th Century was by none of those authors?

What if I told you that the answer was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

A Literary and Cultural Masterpiece

I could probably write an entire article or two on Beecher Stowe or the impact that Uncle Tom’s Cabin had throughout history, and maybe some day I’ll do just that. However, for now, I’ll just be offering a few brief words.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was first published in 1852 in two volumes, which were later combined into a single work (then a stage play, a radio show, and around eight movies between 1930 in the silent era, to a Made-For-Television version in 1987). It is an anti-slavery novel (some call it anti-slavery propaganda) but most agree that it was a major contribution leading up to the American Civil War.

The story it tells is clearly fiction, however it is believed that every character depicted is based on a real person, and the struggles they faced related to slavery (or escaping slavery).

One of the novel’s main characters is a woman named Eliza, a slave who escapes with her son into Ohio after her son was sold, where she meets up with her husband and together they flee to Canada, then France, then Liberia, all while being pursued by Slave-Hunter Tom Loker, and a bunch of horrendous things happen. You know how it is in novels.

A Real World Mystery

If all the major characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin were based on real people, then who was the real Eliza – and what actually happened to her? That is a question that has captivated historians and literary sleuths pretty much since the novel came out.

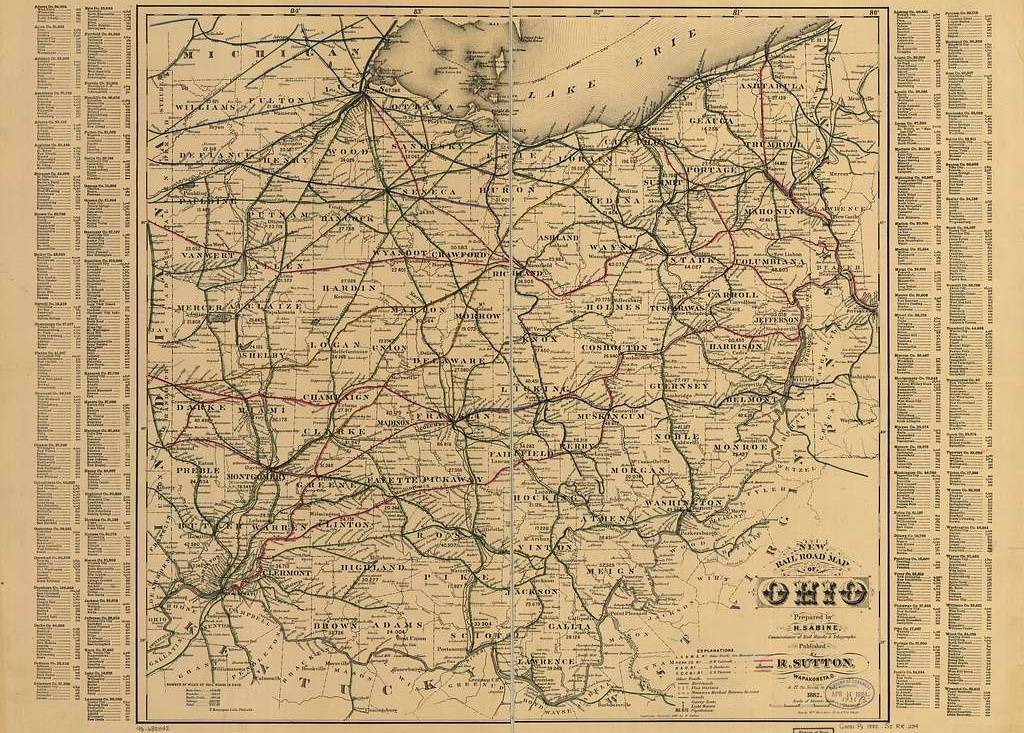

Supposedly, Eliza’s story was inspired from a tale told at Cincinnati’s Lane Theological Seminary. A man named John Rankin told Harriet Beecher Stowe’s husband about the time he watched as a young slave woman crossed the half frozen Ohio River at Ripley, Ohio, with her five year old son, gripping onto floating ice as she made her way toward freedom. She and her son stayed with him for a very brief time before being sent to an Underground Railroad station a few miles upriver where she was given the name “Eliza Harris” before they ultimately made their way to Sandusky, Ohio, and from there presumably Canada. After that little is known of Eliza or what happened to her or her young son.

So, who was she? And what was her true story?

One account we have of this comes from Quaker Levi Coffin who ran one of the Stations not far from Cincinnati. According to him, the lady named Eliza had been a slave in Kentucky, a few miles south of the Ohio River at RIpley. She claims she was treated well by her Master, however her life had not always been easy. She had given birth to three sons, however the first two died as infants. But things were about to get bad as the woman learned that her Master, in a sudden need for some cash, was forced to sell off her son in order to pay off some debt. She had already lost two sons, and the thought of losing a third was too much for her to bear. Late one night, as soon as her surroundings seemed quiet, the woman ran for The Ohio River with her child, then aged about five, in her arms. She had believed that the water would have frozen over on account of the cold weather they had been experienced, but when she reached the water’s edge, she found the ice had already started to break up.

The woman was able to take shelter in a symapthizer’s house on the Kentucky side of the river that first night, but the second night, as Slave Hunters had appeared in the area, she knew she had to make a break for it. As night set in, she ran for the water’s edge and began to cross, clinging on to her child as she made her way across the icy river. Waiting on the other side of the River was abolitionist John Rankin, who led her up the hill to his house, where he operated a station for The Underground Railroad. There, she spent a night or two, then he sent her (along with a few other escaped slaves) on to the next station, a few miles down the Ohio River.

Many years later, a Quaker named Levi Coffin published an account of the story with a few additional details. He claimed that Eliza had come through his Station after departing Ripley and that he and his wife sheltered the group of escaped slaves for a few days until they could continue their journey to Canada.

Many years later, he and his wife (and their daughter) were in Canada when his wife was approached by a former slave who was able to identify her on sight. She wanted to express her gratitude for everything the couple had done for them, but neither Levi nor his wife could remember them. It wasn’t until they told their story, of crossing the icy river, that the pair was able to recall the woman. He did not share any further details than that, leading some to wonder what this woman’s life was like in Canada.

There is, however, a major problem one runs up against when trying to study The Underground Railroad – and that’s how a lot of the information we have about it may or may not be correct.

Due to the very nature of The Underground Railroad, records weren’t kept because the last thing anyone involved wanted was for slave hunters to find out where it was, how it worked, and where it went. Any information at all, even the most simple of details, could prove to be fatal to the operation if word got out.

Also, you have to remember that, politically speaking, it was a hot topic on both sides of the issue (those for slavery and those against). There are, unfortunately, countless examples of people telling stories regarding their involvement that later have been proven to be untrue, presumably for a variety of reasons. Some people, perhaps, wanted to make others think they had been more involved than they actually had been for clout, or even just to make themselves sound better. Other accounts we get third hand (stories that begin with something along the lines of “Back in the day, my father…”) where the person is relaying untrue information because that had been presented to them. Still others have been known to give false information because even after the Underground Railroad was no longer needed or in operation, there were still political or personal ramifications.

The story of Eliza that was given by John Rankin is believed by most historians because there are at least a few elements of the story that have at least some basic corroborating evidence. The same cannot be said about Levi Coffin’s account. It is possible that the story he tells is entirely true, that he did meet up with “Eliza” in Canada and somehow she had a happy ending to her story. But, without more to go on, it’s simply too hard to tell one way or the other. His account was from a self-written book, and some historians seem to think it’s possible he’s just boasting.

So, the mystery remains. Who was “Eliza” in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom Cabin? What happened to her? Was her escape successful? Did her child go on to live a happy and fulfilling life?