If you ever found yourself driving east on New Vienna Road from the town of New Vienna, you would soon come across a road named Gist Settlement Road. It doesn’t look like much – just another country road with a few houses off in the distance, but the unusual name of the road might catch your attention (if you even see it on the small green sign). Make a left onto the street and a minute or two later you’ll come to a bend in the road with a church on one side, a small cemetery on the other. It is at this point that you’ll find yourself in what remains of The Gist Settlement.

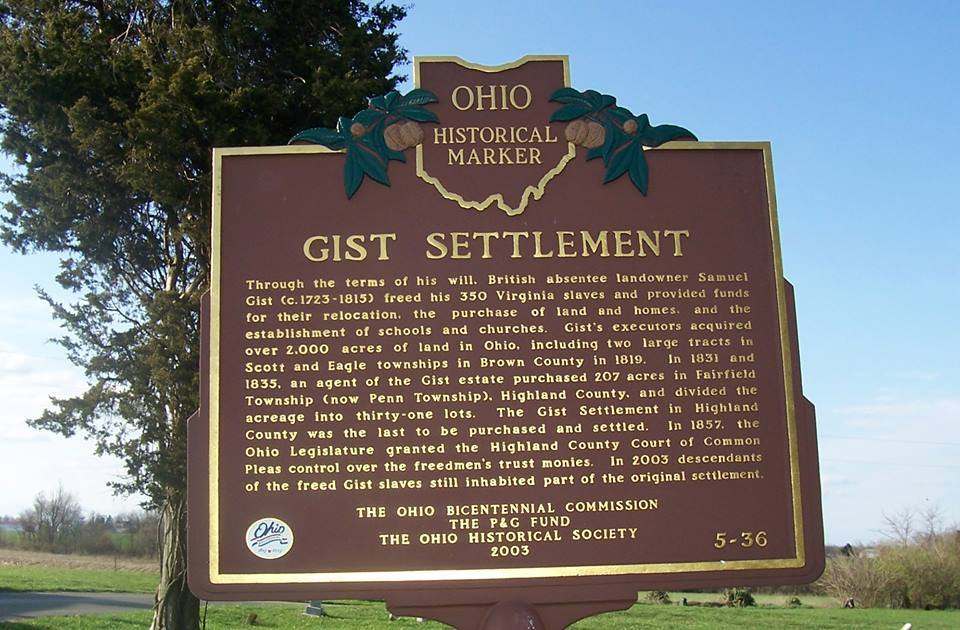

If you look at just about any map, you’re not likely to find The Gist Settlement. In its heyday, there wasn’t much there, besides the church and a small number of houses. Nothing much to grab anyone’s attention or give them a reason to swing by. But, today, just off the road near the bend, you’ll spot a historical marker. Somehow, this area has some level of historical significance.

Which seems kind of strange since unless you’re from this corner of Ohio, you’ve probably never even heard of it. That made me curious to learn more.

Samuel Gist

Samuel Gist was born in 1723 and we’re fairly confident that he never once set foot anywhere in the State of Ohio.

When he was just a small boy, Samuel’s parents died. After that, he was raised at Queen Elisabeth’s Hospital, which wasn’t as much of a medical facility as it was a boy’s school. (Think Hogwarts, but with less magic and located a little closer to Bristol.) In 1939, he became the apprentice to Alderman Lyonel Lyde, employed as a scrivener (which is basically a person who can read and write stuff). His duties there brought him into contact with a man named John Smith (yes, that was his real name) a tobacco farmer from Virginia. He must have had a close relationship with him because after John Smith’s death in 1947, Samuel married his Widow and at the same time became a very wealthy man.

From England, Gist took over and managed all of Smith’s (and his wife’s families) businesses, including the plantation, he got involved in Land Speculation (and was a founding member of The Dismal Swamp Company, to whom he gave both tools and slaves), but we’re getting away from the point here.

So, fast forward to the year 1808. By now, Gist has spent time in Virginia and has learned that running a business in the New Country isn’t as fun or as easy as he had hoped it would be. In fact, he saw the country as a chaotic mess and vowed to never return once he had arrived back in England.

Samuel Gist was also conflicted over the issue of slavery. On one hand, he started to feel that slavery was wrong and was appalled over the mistreatment of many of the slaves (not owned by him). But, also, he could not see how businesses (and in particular his tobacco plantation) could run without them.

When it came time to make up his will, he came to a decision: He would free all his slaves after his death. And he would help them obtain land to live on.

After Gist died in 1815 … things got complicated.

The Gist Settlement

Between the time that Gist wrote his will and the time he died, things in Virginia had changed a lot and those changed caused a lot of problems. Gist wrote his will in accordance to British Law, which was not a problem as long as Virginia was a British Colony. But, now that Virginia was part of a new and independent nation, which had its own laws, that complicated a number of issues when trying to enforce the will.

Another issue is that Gist had relied on his attorney, John Wickham, to handle his legal affairs, but like Gist, Wickham was already an older guy when Gist made the will. When Gist died, Wickham was already in the process of retiring, so it Wickham’s son who had to enforce the will, which made the process take even longer. It should also be noted that this was fairly recent after the War of 1812, and American views about the British were at an all time low, so there were a lot of people who just didn’t care what some Brit had put in his will.

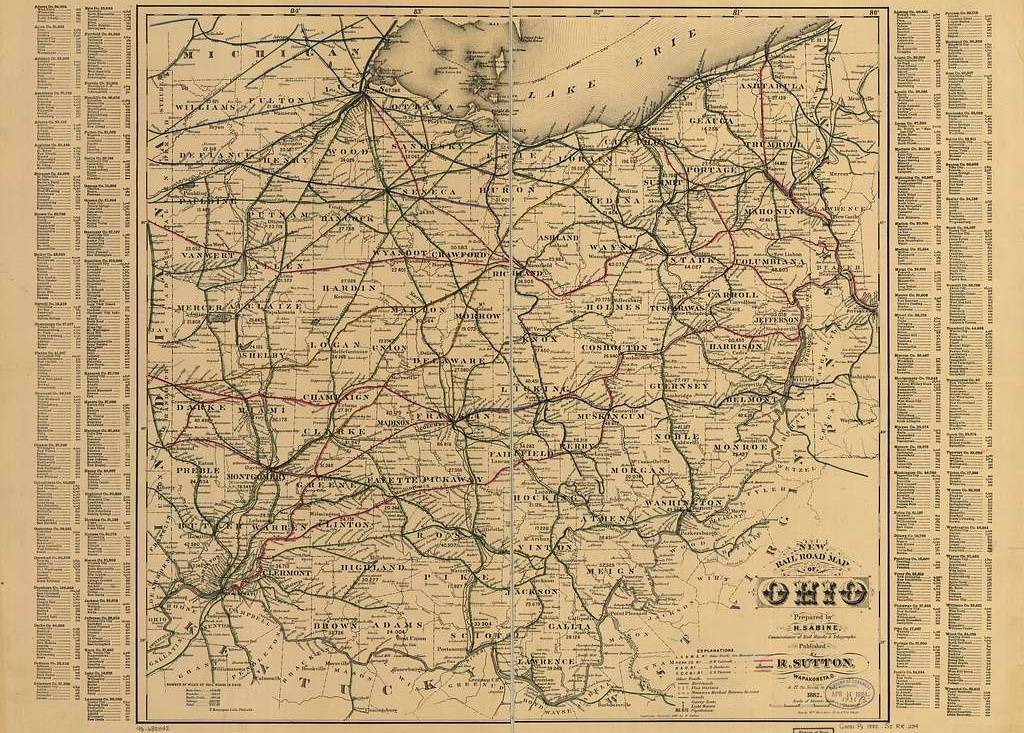

To further complicate the issue, one of the earliest laws enacted in the Virginia Accembly said that any freed slave had to be relocated out of the state within a year. (And as Ohio was the closest non-slave State, that is where they all were headed.) It was difficult enough to get things going when everything was happening so slowly, but it also had a time limit.

There are very inconsistant records regarding how many slaves Samuel Gist “employed”, but most estimates put the number somewhere between five hundred and one thousand, with others reaching as much as one thousand five hundred.

The Gist estate helped procure several plots of land for freed slaves throughout southern Ohio, one of the largest being in northwestern Highland County. Here, besides the houses, they also erected a school and a church building. (The Church still stands today, although it had massive renovations in the 1950s.)

There were other, smaller communities in Brown and Adams Counties.

Manumission

On its own, Manumission, or the process of freeing a slave, was not an easy matter. It isn’t like the movies where you can just give a house elf a sock and suddenly, as if by magic, the creature is free. There is paperwork to be filed, laws that need to be abided by, in Virginia slaves needed to be relocated to Ohio, which meant there had to be some place for them to go to. It was a lot of work for just a single slave, let alone hundreds.

For slaves once owned by Samuel Gist, sometimes there were extra issues, such as how some slaves just didn’t want to go. Or, they didn’t want to go the way they were supposed to go. Some of the slaves took off on their own, without any of the documentation of their freed status, which meant that they could, at any time, be arrested and sold back into slavery again. Others were simply too old to pack up what little they had and make the trek into a new State and start their lives all over again. There were those, too, who did not want to leave loved ones behind, even if those people were to be freed themselves soon (because I suppose in slavery you quickly learn that there are no guarantees) and for some the plantation life was all they had ever known and the prospect of a new adventure was not something they desired.

Eighteen families (or about one hundred and five people) managed to settle in the Highland County settlement that now refers to itself as The Gist Settlement. For a short time, the small community seemed to thrive, although it was met with hardships from time to time. Slowly, though, the numbers began to fall and there are but a few that remain today.

Maybe.

The Gist Settlement Today

The Gist Settlement once consisted of roughly twenty houses, on land that had been purchased by Gist for the former slaves. So, what happens when the slave dies or moves off that land? The answer to that question … we don’t really know.

There was a provision in Gist’s will that stated that the land should be sold to the county and the proceeds were to be put in a fund to help other freed slaves. That’s kind of vague, but okay.

The slaves, though, heard something different. They heard that it was their land, now, so therefore they believed they owned the land outright. They believed that when a father (or mother) died, they could pass that land on to their children, who could in turn pass it on to their children (or, maybe another close relative) and so on.

So, who is right here?

Let’s recap the situation here for a second.

A man in England writes a will which adhered to the laws of England because that’s where he is from and that was where he lived. So, let’s say that The Will is enforceable by British Law.

In order to carry out Gist’s instructions from his will, he will need to (a) free a bunch of slaves and (b) figure out what to do with all the land, in accordance to Virginia Law because that’s where the slaves and property is.

At this point, if there is a conflict between British Law and Virginia Law, what happens then? They didn’t know – so they did the best they could.

Freed slaves were sent to Ohio, which has its own set of laws. Land was purchased here, as directed by a British Will and funneled through Virginia law, so when there is a conflict between British, Virginian, and Ohio laws – then what?

We have absolutely no friggin’ clue.

So, back at the Gist Settlement today. There still is one or two people living there who were directly related to the original settlers. And, let’s say that one of them is getting up there in years. She wants to pass the house she has lived in her entire life on to her daughter, but does she actually own the land and is that something that she can do?

She thinks so.

Both the county and the state aren’t entirely sure.

Now, there’s no hint from any form of local government that they’re about to step in and take that land away from someone, so I don’t want to create a problem where there potentially is none – but what’s stopping them from, essentially, calling those families “squatters” and trying to evict them at some point?

I’m sure that is not going to happen. But, as I said a few paragraphs above … sometimes there are no guarantees.

(Author’s Note) When writing this, I focused mainly on the Gist Settlement of Highland County (located near New Vienna. There are, however, two other Gist Settlements. One is in Eagle Township outside Sardinia, Ohio; the other is in Scott Township outside Georgetown, Ohio.) All three sites are noted with their own Historical Marker. The three communities do share a common history, and a common set of problems. Only minor details (and the individuals who lived there) separate the three.