NOTE: The following post deals with a legal subject matter, and as I am not a lawyer, do not seek legal advise here. The information presented here is purely for educational and historical purposes.

On Halloween in 1963, a police officer named Martin McFadden was doing his thing in Downtown Cleveland when he noticed two men, John W. Terry and Richard Chilton, he believed they were acting strangely. One minute the guys were standing on a street corner, the next, one of them would walk partway down the block and pause to look through a store window. Then, he’d continue down the street, turn around and return to his friend (assuming that’s what they were) after pausing by that same window again. The two guys would talk some more, then the other one did the same thing. McFadden observed the men doing this several times, and then they were joined by a third guy, and that’s when Officer McFadden decided to do something about it. He was convinced that these guys were casing the store whose windows they were glancing into and were most likely about to rob the place.

I assume that he was thinking that because it was Halloween and a lot of people cause a lot of mischief on that day, these guys were up to no good. But, that point is irrelevant.

McFadden approached the guys and demanded to know who they were and what they were doing. The response he got from the guys was described as “noncommittal” and was probably something along the lines of “we aren’t doing anything illegal, go bug someone else.”

This didn’t sit well with Officer McFadden, so he lined the guys up along the side of the road and patted them down, looking for weapons or burglary tools. While he did not find anything to suggest his theory that the guys were about to rob a store, but both Terry and Chilton were concealing guns (pistols) in their pants, so they got arrested.

Let’s pause for a moment here to look at a few key issues.

The 4th Amendment

The text of the Fourth Amendment to the United States of America seems, at first glance, to be rather straight forward. It says:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

However, things in America aren’t always (are they ever?) as simple as they appear to be, so many people over the years have tried to question various aspects of the 4th Amendment. (Others have tried to find loopholes or other ways to invalidate or limit this, but that’s a topic for another day.)

What, for example, is an “unreasonable search and seizure” some people want to know. Is it supposed to be searches and seizures, or can it be just a search without a seizure, or vice versa? What constitutes “probable cause”? And, there are also a ton of “What If” scenarios that tend to pop up, too.

It’s also rather important to consider that the laws (or, at least how laws were interpreted) when this story takes place differs a bit from how it is today. Case in point, by 1963, applying the 4th Amendment outside the Federal Law Enforcement was a relatively new thing. For the first few centuries in America, Cities and States passed their own laws and regulations, which told the police what they could and couldn’t do, and not everyone was all that happy when The United States Supreme Court stepped in and changed things. (There was a lot of that in the 1960s, much of it race based, but I will leave those tales to someone more knowledgeable than I.)

Stop and Frisk is defined as any time an officer stops an individual and checks to see if they have any weapons or illegal things on them. Some form of this practice had been going on for centuries by the time the 1960s rolled in, so it wasn’t a new thing. However, with the Supreme Court now starting to say what city and state police could and could not do – that was new … and it was about to get tested (again).

Terry Stop

Both John Terry and Richard Chilton were arrested and charged with carrying concealed weapons. Most people felt it was an open and shut case – a police officer patted both guys down, both were discovered to have firearms, and both were quickly taken to jail. But, for John W. Terry (or, for his lawyer anyway) he may just have a solid defense. If, according to what the Supreme Court had recently said, city police needed to abide by federal rules for law enforcement, then the police would have needed probable cause to search Terry and Chilton, which they believed the police did not have because there is nothing illegal about walking down a street or peering through a store window … then the Stop and Frisk violated the Fourth Amendment, and anything found during that search would not be able to be used at trial, and without that his client would be guilty.

But, the city judge did not entertain this weird notion because the guy had illegally been carrying a gun and gosh darn we need to be hard on crime, not soft on it … so both men were found guilty. Terry’s lawyers appealed it all the way up to the supreme court with every court ruling against them.

Most people kind of assumed the United States Supreme Court would either refuse to hear the case or say that the lower courts rulings stand, so a few people were kind of surprised when instead of doing that, the court granted something called Certiorari. (This is one of those complicated legal terms that use latin words and phrases and basically means “let’s look this over and clear up some of the confusion, shall we?”.)

Ultimately, the court ruled in an 8-1 decision that yes, Terry’s conviction on the weapons charges should stand. Police officers did not need a warrant to stop someone and frisk them. A large part of this is officer safety, because law enforcement kind of needs to know if the person they’ve stopped (or temporarily detained) is carrying a weapon or not.

However, the courts also stated that law enforcement must have a “reasonable suspicion” that the person they stopped was involved, or were about to be involved in some criminal activity.

The one dissenting justice did, in his limited response, make one very valid point. If this ruling was supposed to clarify a few issues with the Fourth Amendment, it clearly failed to do so as no mention of the Bill of Rights was ever mentioned. He also cautioned that this would give police more authority than judges, in his own words, that would ultimately lead to an imbalance of power.

And, maybe people should have listened to him a bit more.

After the Supreme Court ruling, these stops became known as “Terry Stops” and in effect gave police the authority to stop and frisk pretty much anyone they wanted. They may, and they often did, invent some “reasonable” reason to stop them as history has no shortage of stopping black citizens walking down a street where white people live because that’s totally weird, right? Or, stopping a car driven by a black citizen because … um … blacks can’t own cars or something? Or, stopping a black citizen outside a store because there’s no way that a black person can have a good enough job to afford things like food, or something. Or stopping a black citizen because some anonymous person reported that a black man may have committed a crime in the next town over.

(All of those reasons behind Terry Stops are real, by the way … and not nearly as ancient as one would think.)

Needless to say, the nature behind Terry Stops has been challenged many times in the courts, and often successfully. Also, many cities and states have added even further limitations on these police interactions, such as defining what a “reasonable suspicion” is or limiting the time an officer is allowed to detain an individual during a Terry Stop.

After Terry

I do not want to get into a discussion on whether the Supreme Court’s ruling on Terry v Ohio was right or not, or on the legacy built from that decision. I am not an expert on legal matters, so I will leave that up to them. (If you really want that kind of discussion, there are countless YouTube videos you can easily search for produced by legal professionals, social workers, and civil rights activists that do a much better job than anything I can do.)

That being said … most of the websites, blogs, and podcasts I’ve run across make me think that this case, this law, pertains only to Terry and Chilton and nobody else. Yes, this case was about them because they were at the center of it and Terry’s name is right there in the title “Terry vs. Ohio”. However… It’s also important to remember that Terry was just one individual out of countless others who faced the same situations and circumstances. John W. Terry was the first one who decided to fight what he considered to be an unjust law all the way to the supreme court.

To be fair, neither Terry nor Chilton were the poster child for Law Abiding Citizens. Terry was a heroin addict who spent most of his life in and out of various prisons, and Chilton was later killed while he attempted to rob a pharmacy somewhere in the Columbus area. Therefore, it’s easy for some to say that the decision was right because those two low-lifes got what they deserved. What they fail to take into consideration, however, is that that decision now applies to everyone. Yes, including you. With that in mind, I have to ask, was it still a good call? Was that fair to everyone?

So, what happened to the three people involved? Well, as I said before – a few years after his arrest, Richard Chilton tried to rob a Columbus area pharmacy and didn’t make it out of the store alive. John W. Terry spent the remainder of his life in and out of prison, which is where he ultimately died.

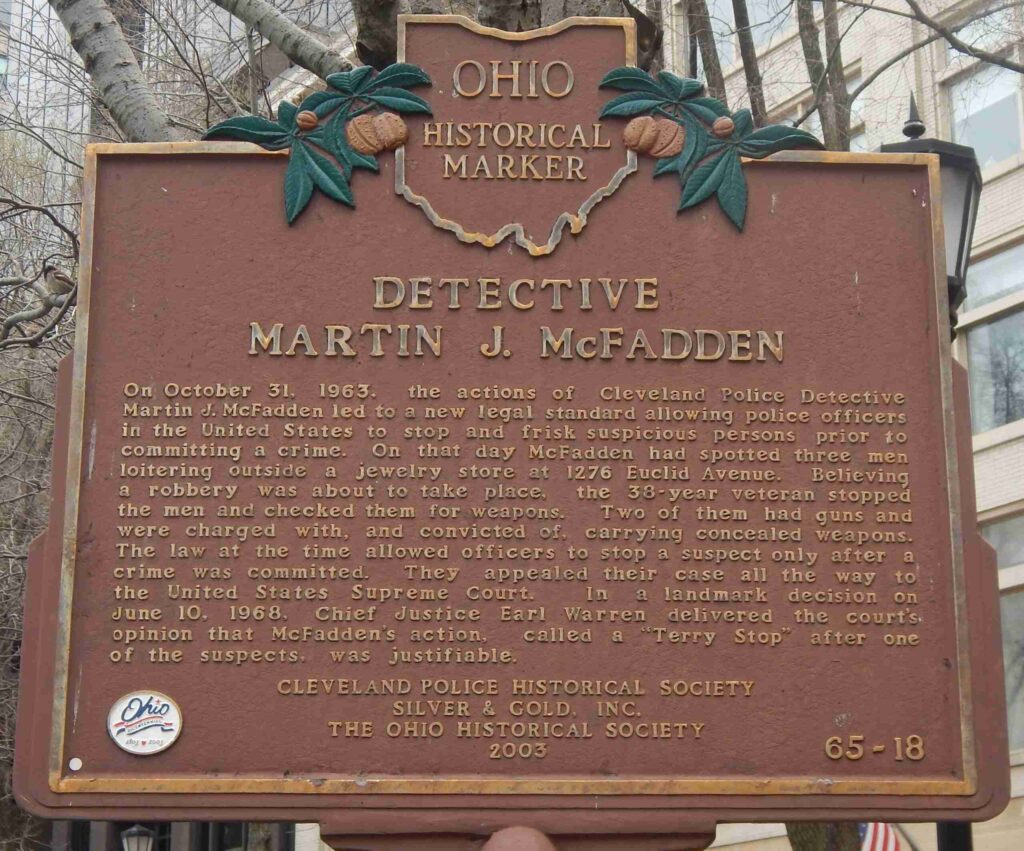

That leaves us with one person, Officer Martin McFadden. Well, as you might have guessed, he kind of became a bit of a celebrity, especially around law enforcement circles. After all, if you squint at it in the right light, he made it so police officers could stop and detain anyone and everyone they wanted, as long as they could come up with a “reasonable” explanation to do so. He was so loved that in 2003, at the intersection of Huron Road and Euclid Avenue, the city of Cleveland erected an historical marker to honor the guy. (It’s in the US Bank Plaza just off the Huron Street sidewalk.)