NOTE: The following post deals with a legal subject matter, and as I am not a lawyer, do not seek legal advise here. The information presented here is purely for educational and historical purposes.

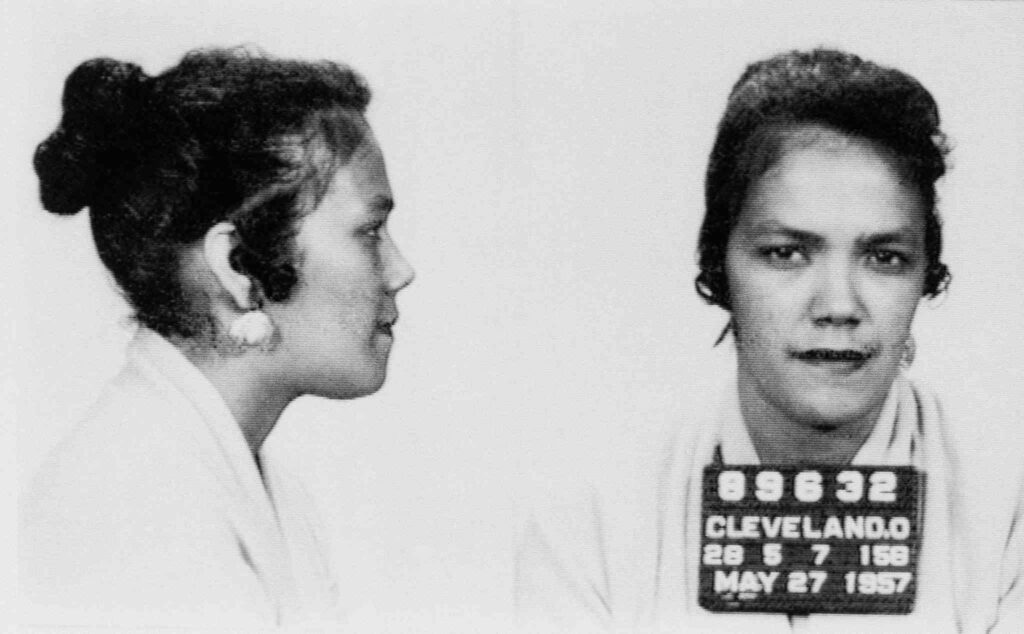

One day (I’m not sure if it was May 23, 1957 or a few days after that) a lady named Dolly Mapp was chilling at her Cleveland home when a small group of police officers knocked on her door. They had just received a tip that a wanted criminal, Virgil Ogletree, was staying with her, and they also thought that maybe they mind find some evidence of her boyfriend’s illegal gambling operations. Virgil Ogletree, the police believed, was probably somehow involved with the bombing of Don King’s house, which Dolly may or may not have been involved in, too.

Dolly left the police standing outside while she rushed to the phone to place a call. She returned to the door a few moments later and informed the cops that she had just called her lawyer and on his advice she wouldn’t be letting them into the house without a warrant. At that point, most of the officers left, but a few stayed behind just in case that Virgil guy tried to sneak out the back door, or something.

A few hours later, the police came back, kicked in her door, thrust a piece of paper into her face saying it was a search warrant as they began to look through her house. Dolly managed to snatch it out of the policeman’s hand, and believed it didn’t quite look right. She stuffed the paper into her bra, thinking that the police wouldn’t stoop so low to reach into her clothes to get it, but she was wrong. This was the last time anyone saw that paper, so there’s no way to tell if it really was a search warrant or not. Because Dolly was a bit angry at having her door knocked down, not being allowed to see or retain the (so-called) search warrant, they decided she was being too combative and placed her in handcuffs for the remainder of the search.

The police did find Ogletree hiding in a downstairs apartment, so he did get arrested. The police did find some blank betting slips in the basement, as well as a box of pornography and a pistol. Dolly was therein arrested on a misdemeanor possessing numbers-game paraphernalia charge. It didn’t take long for her to have her day in court, which ended in her acquittal.

A few months later, the police were back. They had developed a solid case against an associate of hers, Shondor Birns (a fairly well known gangster at the time with heavy ties to organized crime) and they needed her help.

In my mind, she has a large dramatic monolog with a string quartet playing in the next room over, where she berated the officer for knocking down her door, having her arrested on apparently bull-crap charges, not to mention the way that whole “search warrant” thing played out … so she told the cops where they could shove that request. That’s probably not (exactly) how it happened, but whatever did, she told the cops no. She wouldn’t participate.

And then she was promptly arrested…

For processing pornographic materials.

And Now, Some Background

Since the time Law Enforcement first became a thing until some time around the 1940s, you had two types of police. First, you had Federal Police that got their power from the United States Constitution. And you had non-Federal police, such as city or state officers, that got their power from whatever laws were enacted on a state or municipal level.

One of the many (understatement) problems with the system being set up this was is that many citizens will look at the constitution, and, say that pesky Fourth Amendment, and think that the police should (or should not) do certain things. But, for the longest time, the constitution only applied to Federal agents, so State and City cops could easily say, “Nope, that law doesn’t apply to us” and nobody could stop them.

This may be an over-exaggeration, but looking back it really does seem as if State and City police officers could literally do whatever they wanted, unless there was a law enacted telling them no – and even then they often found some way around that.

That all changed with a series of legal cases from around the 1940s and the end result is that the United States Supreme Court decided that the limits of law enforcement, as well as the protections granted to the general public, had to be applied to everyone, period. It no longer mattered if it was a lowly state cop or a federal agent. But, since that is an easy solution to a complicated problem, it would require even more cases to smooth out the rough edges and that process is still going on today (and probably always will).

Is there any background to that whole Mapp situation that people should know? Well … maybe.

Dolly Mapp was, for the part, a fairly minor side character. The two big people (outside law enforcement) were Virgil Ogletree and Don King. Ogletree had made a pretty good living for himself in the organized crime world of sports betting, and in particular betting on boxing matches. His gig was clearly good for himself, and it was good for some people, but not everybody.

So, along comes a young man named Don, who had recently graduated from John Adams High School in Cleveland and apparently very much into boxing himself. However, unlike Ogletree who saw boxing as little more than a way to make money, King seemed to really enjoy the sport. Not that any of this matters in a legal sense, but maybe it will help explain how things turned out in the end.

Dolly Mapp, likewise, was into the sport of boxing. She had married a boxer, many of the people she hung out with were boxers, and let’s not forget she was renting one of her basement rooms to Virgil Ogletree.

Anyway, Don has a few ideas about how to make betting on boxing better (and, maybe, less-illegal) and when he takes his ideas to the mob that is currently running boxing betting, he’s told to take a hike. Rather than do that, Don talks to some of the boxing insiders he knows, and starts to set up his own numbers game. But, before he can get very far, word gets back to Ogletree and his mob gang, someone puts a bomb in Don’s house, the bomb goes BOOM and now this whole sordid business is quite a mess.

To make a short story a bit shorter, Police look at the Don King’s phone records. They already suspect (and are pretty sure) that Ogletree had something to do with the bombing, so they want to talk to him about that. Every time that they knew Mr. King was talking with someone from Ogletree’s office, the calls were coming from the address of one Dolly Mapp, whose husband had been a boxer, so they were fairly sure that Ogletree lived there.

Needless to say that when they went to the address to look for the guy, and Mrs. Mapp told them to get lost without a warrant, they were a bit angry and … you know how that played out.

Mapp versus Ohio

So, just to recap: Mrs. Mapp is home when the police come to her house looking for someone. She says get lost if you don’t have a warrant, so the police run out and try to get one. Only, they can’t so they pretend they got one, smash her door down, detain and arrest her for being non-cooperative while searching the house. They find Ogletree, arrest him, but even though they don’t find anything that connects anyone to gambling on boxing, they do find some empty forms that could be used in gambling, they find a gun, and they find some pornography, which was not just morally scandalous at that time, it was likely also illegal. Mapp was soon acquitted on the charge of not helping the police even though they didn’t ask nicely. A few months later, the cops show up again at her doorstep and politely ask her to help them convict Ogletree, and when she tells them to get lost, they arrest her because the last time they were there, they found all that porn and somebody has to pay for that. Mapp had said (even back during that first search) that the boxes with the porn and pistol had been left by the previous owner and she wasn’t sure what to do with it, so she stuck it in the basement until she could figure it out. The cops pretty much told her they didn’t care, it was in her basement, therefore she’s guilty.

After a brief trial, Dolly Mapp was found guilty.

She appealed the decision up through the state courts, all of whom said that since the immoral photographs were discovered on her property, that meant they were in her possession, and therefore her conviction stands.

But, Mapp (and her attorney) kept trying to argue that whether or not she was guilty wasn’t the issue. They claimed that the search wasn’t fair, to begin with, because the police had failed to obtain a search warrant, the police lied about having one, and for the most part the police weren’t held accountable for their mistakes, so the whole business was unfair at best and criminal at worst.

Fruits of the Poisonous Tree

The United States Supreme Court saw things a bit differently than the lower courts. For them, it wasn’t an issue of whether or not Mapp was guilty, as whether the obscene materials were hers or not, they were in her possession and therefore her conviction would stand, except for one thing – when the police searched her house without a warrant (or without being able to prove they had gotten one, which they had ample opportunities to do and failed each time) that violated the United States Constitution and therefore itself was illegal.

For that reason, Mapp’s conviction must be overturned because law enforcement can’t use illegally gathered evidence at trial and since that was the only evidence they had, Mapp wouldn’t have been convicted.

Thus began a short phrase that would ultimately go on to become very popular in police procedural and legal drama television shows: The fruits of the poisoned tree.

And, it very well may have also gone on to be one of the major consideration factors in the passing of the 14th Amendment.

After Mapp

A lot of things changed after the Mapp decision, but most of them were the result of further legal cases and court clarifications. So, in the general scheme of things, Mapp’s legacy wasn’t so much in the decision itself, but how it laid the groundwork for other cases to come in the future.

For example, Mapp said that police must obtain a search warrant before they enter or search someone’s house. Later courts ruled there could be exceptions, such as Plain View. (If, for example, a police officer was looking through Aunt Irma’s window and saw her violently attacking her neighbor, Mr. Akbar, with a butcher knife, they had every legal right to break down her door and arrest her.) There are too many exceptions to name here, but I’m sure you get the idea.

As far as most of the people involved in this story, they all for the most part, kept doing their thing, as far as I can tell. The only real exception in all this was Don King, who after spending years on the outskirts of organized crime and dealings with a legal system that seemed to be set up to favor whites over blacks.

In and around the 1970s, King’s career trajectory really took off after he convinced a popular boxer by the name of Mohammad Ali to join a celebrity boxing match to help raise money for a Cleveland Hospital, then a few years later got involved promoting the infamous Ali-Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle” match in Zaire. Following that, Don King was appearing in boxing matches everywhere and had become so popular that he regularly appeared on a variety of daytime and evening talk shows, causing everyone to wonder, “Did you mean to do that to your hair?”