Every state has towns (cities, villages, unincorporated areas) with names that are a bit unusual. We’ve already noted (and celebrated) a few of those names, and then I ran across… well, almost seems as if the state of Ohio said, “Here, hold my German Beer and try to pronounce this one: Gnadenhutten”

For the record, it’s pronounced …

jə-NAY-dən-hut-ən

… I think.

Translated from German, it means “huts of grace”

And, how it got its name is just as interesting as what happened there later.

History of Gnadenhutten

The settlement of Gnadenhutten began in 1772, just a few months after the Moravian Church leader Joshua settled about ten miles north in a community they called Schoenbrunn. Both communities were made up of a combination of German Immigrants and members from the Mohawk or Lenape (or Delaware) tribes – everyone wanting to follow the Moravian Church teachings. Before moving into the area (remember, Ohio wasn’t a state yet) they had all resided in Pennsylvania.

Just as a side note here, one of the new families of Gnadenhutten, a German couple named John and Ruth Roth, had their first child on July 4th, 1773, several months before the settlement’s first anniversary. This child, which they named John Lewis, would become the first white child born on what would eventually become Ohio soil. However, a month later the Roth family moved to Schoenbrunn.

Life in Gnadenhutten seemed rather idyllic in the Moravian communities and in no time at all began to prosper. History records that sixty houses were built during that first year.

Meanwhile, back east, the events leading up to the American Revolution were well underway and the fledgling nation was preparing for war. But, for the Moravian Christians who were strongly pacifists, this didn’t seem consequential at all.

Even though the people managed to remain neutral during the revolution, British soldiers accused them of giving aide to the American patriots, and they couldn’t let that stand. The British detained Moravian Reverend Zeisberge at Fort Detroit as they tried to push the Lenape people farther west towards the Upper Sandusky area. Yet, a few were allowed to return to their homes to collect supplies and belongings.

This didn’t set very well for a couple of British militiamen, most notably one named David Williamson, who tricked them into giving up anything that could be used as a weapon. This was in retaliation for the ongoing battles between European settlers and the indigenous tribes, and in particular a rather bloody battle that had occurred in Pennsylvania a few weeks prior.

March 8, 1782 The Gnadenhutten Massacre

During this period in history, the general consensus of most people was that you were either for The American Revolution, or you were on the side of the British. This was not always the case, as the Moravian people illustrate. Because of their pacifist nature, they didn’t want to take sides – they just wanted to be left alone and let them do their own thing. The problem with that was that neither the British, nor the new American revolutionists knew what to make of them. Nor could they trust them.

So, when the British militiamen arrived in town and took all their (so-called) weapons away, nobody was prepared for what happened next. They accused the Moravians of being spies and giving aid to American revolutionists, even though there’s no real evidence to suggest this.

It didn’t take long for the Moravians to realize they were about to be slaughtered. Yet, when they were allowed to pack up their crops and belongings, they gathered at the local church and began to sing hymns.

While a few of the British were still keen on continuing their plans to wipe out everyone, others had a change of heart. Not enough of one to help the Moravians, but just enough so they could tell themselves they didn’t actually participate in any of the killings. Still, by the end of the night, all sixty homes had been burned to the ground. The only survivor was a single young boy.

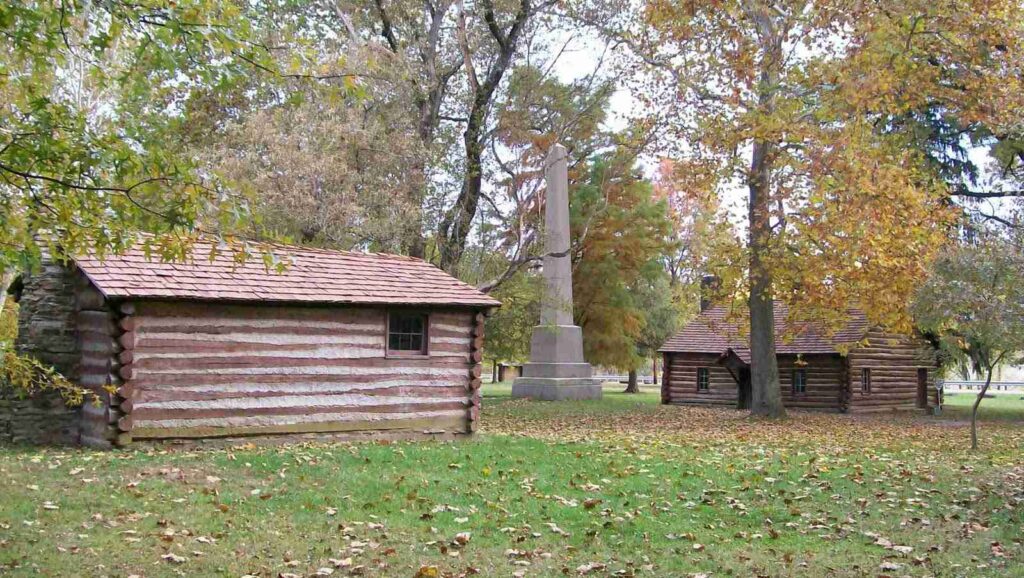

A Moravian missionary named David Zeisberger would declare everyone among the dead as “Christian Martyrs” and would build a shrine to them in the town’s Moravian church. A Century later, United States president Teddy Roosevelt would say the Gnadenhutten Massacre was “a stain on frontier character that the lapse of time cannot wash away.”

Gnadenhutten Today

Today, the village of Gnadenhutten described itself as “an historic village in beautiful eastern Ohio” and continues to pay homage to its bloody past. It boasts over a thousand inhabitants living in town, which contains just shy of one square mile of land.