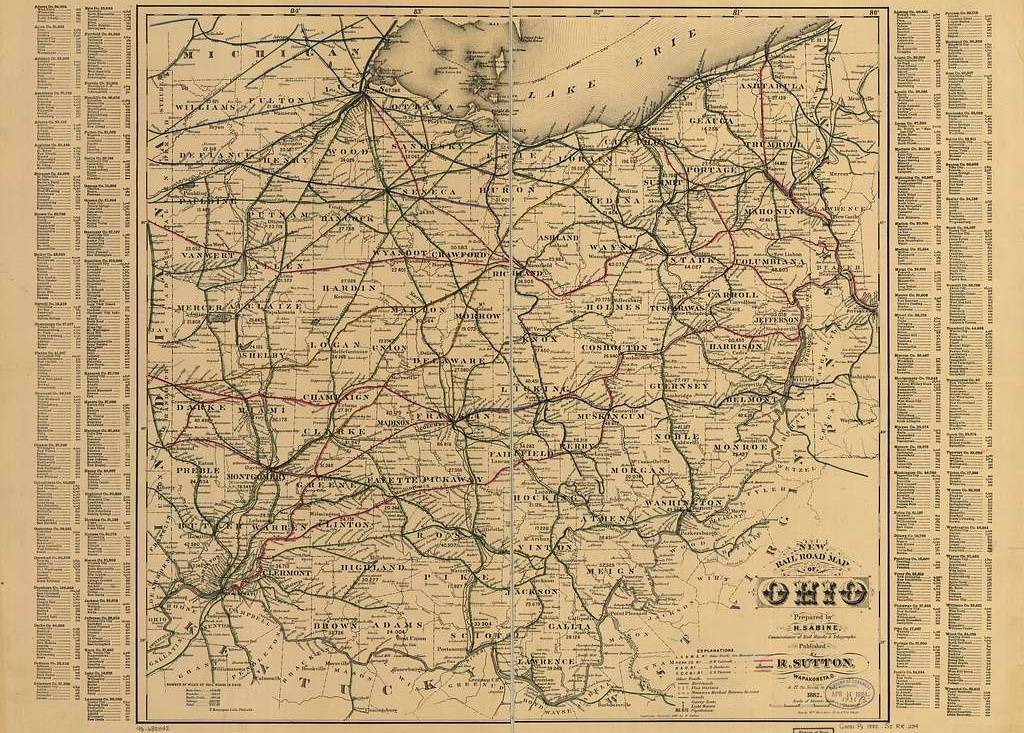

If you look at a map of Ohio, you will see that the state has a rather distinctive shape. Look a little closer and it isn’t hard to figure out some of the reasons why. The most obvious would be the southern border that follows the shape of The Ohio River. In the northern part of the state, Lake Erie helps form at least a part of the boundary, but when you look at the rest of the border, you’re bound to see a few things that, at first glance, appear kind of odd.

The boundary line starts just north of the city of Toledo. From there, it heads in a westward direction with a slight slope to the south to where it meets the Indiana border. You may also notice that Indiana’s northern border is, in fact, a due east-west line that starts a bit north of the Ohio border … so, it’s relatively clear that there was something weird going on here.

If you are looking for an easy explanation, you can point to facts like how maps weren’t as accurate when Ohio (and Indiana and Michigan) became a state as they are now. Or, you can point to some vague language that points to locations on those erroneous maps. And, in a way you’d be right. But, when it comes to history – nothing is that simple.

After all, it doesn’t include that time when the State of Ohio went to war with the Territory of Michigan.

In order to understand how all that came about, we need to go back to The Northwest Ordinance (of 1787).

1787 – Northwest Ordinance – Northwest Territory

What we, today, call the Northwest Ordinance is actually An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio. Enacted on July 13, 1787, it essentially set claim to all of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River and north of The Ohio River. This land had, for a short time, been claimed by Brittain (after they battled the colonies, the French and the Spanish for it).

Even after that, there were still some British troops that weren’t all that happy to leave. And, there were still some indigenous tribes in the area saying, “hey, we were here first”.

The Northwest Ordinance did a number of things beyond the new nation essentially marking its territory. It created a way that people could own property in the area, it determined how portions of this land would be set aside for things like education (building schools) or public use. It abolished slavery in the territories (although nowhere else). It set up laws and established natural rights for residents, and more.

But in Article 5, it set up how the land was to be divided up into new states.

There shall be formed in the said territory, not less than three nor more than five States; and the boundaries of the States, as soon as Virginia shall alter her act of cession, and consent to the same, shall become fixed and established as follows, to wit: The western State in the said territory, shall be bounded by the Mississippi, the Ohio, and Wabash Rivers; a direct line drawn from the Wabash and Post Vincents, due North, to the territorial line between the United States and Canada; and, by the said territorial line, to the Lake of the Woods and Mississippi. The middle State shall be bounded by the said direct line, the Wabash from Post Vincents to the Ohio, by the Ohio, by a direct line, drawn due north from the mouth of the Great Miami, to the said territorial line, and by the said territorial line. The eastern State shall be bounded by the last mentioned direct line, the Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the said territorial line: Provided, however, and it is further understood and declared, that the boundaries of these three States shall be subject so far to be altered, that, if Congress shall hereafter find it expedient, they shall have authority to form one or two States in that part of the said territory which lies north of an east and west line drawn through the southerly bend or extreme of Lake Michigan. And, whenever any of the said States shall have sixty thousand free inhabitants therein, such State shall be admitted, by its delegates, into the Congress of the United States, on an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatever, and shall be at liberty to form a permanent constitution and State government: Provided, the constitution and government so to be formed, shall be republican, and in conformity to the principles contained in these articles; and, so far as it can be consistent with the general interest of the confederacy, such admission shall be allowed at an earlier period, and when there may be a less number of free inhabitants in the State than sixty thousand.

1802 – 1816

The Enabling Act of 1802 was passed by The Seventh Congress and laid the foundation for Ohio to become a state. They tried to use the boundary line between Lake Michigan and Lake Erie to set the state’s north-western border as stated in the Northwest Ordinance, but there were a few issues.

One issue is that the maps at the time weren’t always as accurate as they are now. In fact, there was quite a bit of debate as to just how far south Lake Michigan extended. It also wasn’t clear exactly where the line was supposed to meet Lake Erie.

On March 1, 1803, Ohio becomes a state. The state lays out the western portion of its northern border just north of where Toledo is today. (At that time, it was known as The Port of Miami, as that was the mouth of the Great Miami River.)

In 1805, The Territory of Michigan was officially formed. However, when they were laying out their southern border, they disagreed on where the ordinance like should have been. The way they saw it, it should have been a bit southwest of where Ohio said it was. And, over the next few years, they started to gear up for a fight.

In 1810, The Territory of Michigan sought out some help from Congress, but quickly discovered they had their hands full with other more pressing concerns – most notably that whole War of 1812 business, so any word from the federal government would have to wait.

After the war was over and congress was ready to start looking at the states again, in 1816, they allowed The Territory of Indiana to become a state. And, once again, there was an issue with that state’s northern border. In an attempt to give Indiana some access to Lake Michigan, their border was officially placed about ten miles north of the boundary line Ohio had been using.

At this point, Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass was becoming a bit perturbed. Once again, he requested congress for a National Survey – one he was certain would end in his favor based on how he interpreted the words used in the Northwest Ordinance. And, he made it clear that he was gearing up for a fight.

1817-1819 – Land of Confusion

In 1817, the Surveyor General of the Northwest was a man named Edward Tiffin, who by then held several political offices in Ohio, including being the first Governor of Ohio. As Surveyor General it was his civic duty to address the border dispute. He sent a young man named William Harris to take a survey. Harris placed the line just north of the city of Toledo, where the state boundary is today.

This was not good enough for Michigan’s Territorial Governor Lewis Cass. To him, Tiffin was biased on account of his history as an Ohio politician. And, since Tiffin asked Harris to do the survey he refused to accept the results.

The following year, at Cass’ insistence, President James Monroe ordered a new survey, calling on John A. Fulton to perform it. He placed the borderline around ten miles south of the line Harris had, and south of the city of Toledo. This, Ohio refused to accept, suggesting that Fulton had been corrupted by Cass. That year, congress admitted Illinois into the union, and in a partial attempt to settle Michigan’s grievances, they enlarged the Michigan Territory to include what is now considered the North Penninsula.

The Toledo Strip

Both the State of Ohio and the Territory of Michigan claimed ownership of what became known as The Toledo Strip – the area of land between the Harris Survey Line and Fulton’s. This strip of land was five miles tall at the Indiana Border, and about eight miles on the Lake Erie end with seventy miles between them. Both Ohio and Michigan had legitimate reasons for thinking the land belonged to them … and this small strip of land was politically and economically important to both, as well.

The land was particularly fertile, especially closer to Lake Erie, and a great place to grow resources like corn and wheat. But, the main interest appears to be the Maumee River.

At this point in history, before roads and railroads could get you anywhere you wanted to go, people traveled by boat via the great lakes and rivers. As most of this was going on, The Erie Canal was being built, which was built to connect Lake Erie with the Atlantic Ocean. Further canals were being built in Ohio, connecting the lake with the Ohio River, and more were being planned to support this westward expansion. Ohio was planning on building two canals of its own, one of which (the Erie and Miami Canal) would start at Cincinnati and end in the Maumee River, just west of Lake Erie – in the middle of the Toledo Strip. This is perhaps the largest reason why both Ohio and Michigan wanted control over this small strip of land.

Ohio was slowly establishing itself, building and growing into the state it would become. It had some larger cities like Cincinnati and Cleveland, and smaller towns and villages like Chillicothe and Marietta … and the territory of Michigan wasn’t seeing much of that kind of action. So the prospect of having a port city like Toledo would mean a massive boost in their economy.

1828 – Leadup To War

By 1828, the Territory of Michigan had petitioned for statehood a few times, and each time the result was the same – it wasn’t going to happen as long as their southern border was in dispute. This time, they tried a new tactic, getting The U.S. House Committee on Territories in the United States House of Representatives involved. They pointed to the wording used in the Northwest Ordinance, which to them was the basic issue.

After much discussion, they announced that when the Northwest Ordinance was written, they intended it to mean that each of the new states had equal accessibility to the great lakes. If they were to decide with Michigan, it would block Indiana’s access to Lake Michigan, leaving them with no access to the great lakes at all. Likewise, granting Michigan ownership of Maumee Bay would give them an unfair advantage against Ohio. Besides, after Illinois became a state and Michigan was granted those additional lands, it already had access to Lake Erie, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Superior. They felt Michigan had enough great lake access already.

Yet, for some reason, they refused to act on this, leaving everything pretty much unchanged.

At the same time, Michigan had already started a new settlement they called Port Lawrence, in the northern part of Toledo, and now they were using that as a more major seat of government, and as a militia base.

In 1832, Michigan once again petitioned for statehood, and once again Congress refused the request because of the border dispute. However, they did order yet another survey, this one to be performed by a man named Andrew Talcott. This survey was completed in 1834 and suggested that Michigan be granted control over The Toledo Strip. However, unlike all the previous land surveys, it didn’t do anything to end the conflict.

On February 6, 1835, Ohio lawmakers (at the bequest of then-governor Robert Lucas) enacted a law extending their jurisdiction over The Toledo Strip, which they had already been claiming for years. Less than two weeks later, the Territory of Michigan would respond with the Pains and Penalties Act, which penalized anyone in the Toledo Strip siding with Ohio with a thousand-dollar fine and up to five years in a hard labor camp.

Both sides had just, effectively, declared war.

1835 – The Toledo War

After Michigan passed the Pains and Penalties Act, the Ohio governor sent three commissioners, Uri Seely, Jonathan Taylor, and John Patterson, to Perrysburg (just south of Toledo) to see what they could do to drive officials from the Territory of Michigan back above what they claimed was the state line. The date these commissioners were to arrive in Perrysburg – April 1 … no April Fools Joke.

Michigan’s acting Territorial Governor, Stevens T. Mason, and his father John Thomson Mason were worried, but the father was getting a plan. He wanted his son to be slow in responding, actually allowing these commissioners into The Toledo Strip, and waiting for them to make a mistake and become the aggressors. This, he was sure, would put Ohio in such a bad light, that they were certain to win this war.

Or, as Mason (Jr) put it, “Let him get on our soil, arrest him, strike the blood at once, disgrace him and his state, and end the controversy.”

Having said that, he then orders even more militia into The Toledo Strip.

Before long, Mason receives a letter from John Forsyth, The U.S. Secretary of State, informing him that if he continues the Pains and Penalties Act, and continues to “arrest” Ohio citizens, President Andrew Jackson or his administration would get involved and put an end to this conflict. To say this irritated Mason would be an understatement. He immediately wrote Forsyth back a scathing letter, demanding Jackson remove him as Governor if they were going to make him powerless over matters in his own territory.

The Ohio Governor was also writing the president, saying this conflict had gone on long enough, begging for some kind of arbitration. On March 24, 1835, Jackson sent Benjamin C. Howard of Baltimore, and Richard Rush of Philadelphia to act as arbitrators.

On April 1, 1835, Michigan held an election for township officials in The Toledo Strip. The following day, the delegation of Ohio commissioners arrived in Perrysburg. The day after that, Benjamin C. Howard and Richard Rush arrive in Toledo.

On April 6, 1835, Ohio held elections in The Toledo Strip to elect officials.

On April 8, 1835, the Monroe County (Michigan) Sheriff moved into Toledo and started arresting as many people as they could under the Pains and Penalties Act.

That evening, the Sheriff, along with thirty-five to forty men, arrived at the home of Major Benjamin Franklin Stickney, one particular outspoken supporter of Ohio. Even though Stickney’s daughter sounded the alarm as soon as the men reached the property, several people, including Stickney’s daughter, were dragged into the street and hauled off to Monroe County. The possy attempted to gouge out the eyes of one of Stickney’s guests, George McKay. As soon as they arrived in Monroe, a mock trial was held in the middle of the night and the prisoners were sentenced to huge fines and hard labor.

The following day, several hundred from the Michigan militia began riding their horses around the Toledo area with the Ohio Flag dragging on the ground from their horse’s tails.

The Ohio Governor started trying to amass even more volunteers and fighters, hoping to get ten thousand men into the Toledo area.

Rush and Howard, the arbitrators sent by President Jackson, reported the situation to him and with the President’s authority contacted Michigan Territorial Governor Mason with three ultimatums.

- They were to leave the Ohio Commissioners alone and allow them to continue to the Harris Line.

- The people who resided in The Toledo Strip could decide for themselves if they wanted to lived in Michigan or Ohio – at least temporarily.

- And finally, Michigan must not enforce the Pains and Penalties Act, nor were they allowed to try anyone else under the act until Congress had a chance to act.

As you might expect, Mason thumbed his nose at this and refused to comply.

The Battle of Phillips Corner

On April 25, 1835, the Ohio surveyors (along with forty armed men) reached an area called Phillips Corners (which today is at the intersection of State Routes 109 and 120, just east of Lyons) where they set up camp for the day. Unfortunately, a spy sent by the Michigan undersheriff spotted them and reported their location back to Mason and his men.

Around noon the following day, the Sheriff arrives at the camp along with several armed men and began firing. According to the Ohio surveyors, they were being shot at – but, according to the sheriff’s men, they were just shooting way above their heads to alert them of their presence.

In a sudden fit of panic, the surveyors run south as fast as they could trying to exit the disputed zone while several of their guards try to hide in a nearby log cabin. These men were quickly surrounded and ultimately surrendered, were arrested, and taken to a nearby Michigan jail. Of the six men arrested, five posted bail the following day. The other dude refused bail as a matter of principle.

The five men returned to their base camp at Perrysburg and everyone starts trying to figure out what to do next.

Mason, several days later, makes the first move. He agrees to release everyone arrested under the Pains and Penalties Act, and he agrees to allow Ohio to set the state border, except he wants the city of Toledo to be in Michigan. Ohio governor Lucas quickly sends word back to Mason that this was unacceptable.

Both sides appeal, once again, to Andrew Jackson, but once again the American President is reluctant to rule one way or another.

It seems clear that to Jackson, this was about more than just a simple boundary dispute. The State of Ohio and the Territory of Michigan were neighbors, and he felt they needed to find a way to reside side-by-side and settle their own disputes. If they couldn’t come to an agreement on something like this, what else could they fight over? And, if both states forced the federal government to settle things, that would set an interesting precedence allowing all the other states and territories to settle their disagreements through Presidential involvement. And nobody at the time thought that was a good idea.

Besides, Jackson also knew that both Congress and the House of Representatives had already tried to intervene, and that only seemed to make matters worse. Michigan claimed the survey commissioned by Congress was biased toward Ohio because the man who performed the survey had started his political career as Governor of Ohio. When the House of Representatives got involved, they looked at the wording of the Northwest Ordinance, and the intentions of those who wrote it and came to the conclusion that the Ohio and Indiana state lines were more in tune with what the drafters wanted and that Michigan’s idea was very unfair to its southern neighbors. But, they refused to officially act on that finding, making it pretty easy for both sides to ignore.

After the Battle of Phillips Corner, Ohio’s volunteer army was disbanded. Governor Lucas was clearly getting flustered by this whole affair. At the same time, the Michigan Territorial Governor was calling the battle a success, using it to rile up his troops. Michigan seemed excited to take this war to the next step.

1835 – Bloodshed

After the Secretary of State wrote to the leaders of both Ohio and Michigan, begging them hold off on any state boundary action, both sides indicated they had no intention to comply. Michigan held another Constitutional Convention in Detroit – they were once again going to petition for Statehood.

The Ohio Governor, taking a page from the Michigan playbook, passes a few laws:

- Ohio created a new law that would sentence anyone to seven years of hard labor for the “forcible abduction of citizens of Ohio.”

- A new county was created, Lucas, and its county seat would be the city of Toledo.

- The legislature asked for three hundred thousand dollars to implement this, adding another three hundred thousand later if needed.

- A Court of Common Pleas was established and set to begin on September 7th (the first Monday in September).

With their own version of The Pains and Penalties Act, Ohio lawmen and militia began entering the toledo area to arrest Michigan sympathizers, or people conducting Michigan business in the contested zone.

In retaliation, Michigan’s Monroe County Sheriff Joseph Wood was sent to the Stickney Home, but this time his focus wasn’t on Major Benjamin F. Stickney, but on his younger son, Two. (Genealogical records tell us that Major Stickney had two sons, One, born in 1803, and Two, born in 1810. He also had four daughters, Louisa, Mary, Molly, and Indiana. So, yeah, Major Stickney’s two sons were really named One and Two.)

When Wood’s undersheriff attempted to arrest Two Stickney, the young man retaliated, pulled out a dagger, and stabbed the undersheriff in his side. As far as wounds go, it was hardly serious. But, it would be the first time during the entire Toledo War that blood would be shed.

Following this, Two ran from the house and made his way across the Maumee river – back onto undisputed Ohio land. Major Stickney, and several other men, were arrested and hauled on horseback to Monroe County. Territorial Governor Mason demanded that the Ohio Governor extradite Two Stickney to his men. Lucas responded in the negative because the stabbing took place on Ohio soil.

Throughout the month of August, Ohio continued to send militia into Toledo to help in protecting the upcoming Court of Common Pleas. Michigan, on the other hand, tried to petition the legislature, trying to claim the Ohio Governor was trying to murder Michigan citizens, offering Two Stickney as proof. This just didn’t work.

On August 29th, Andrew Jackson had enough. He removed Mason as the acting Territorial Governor of Michigan.

Mason’s first replacement, Judge Charles Shuler of Pennsylvania, refused the position. Jackson then turned to John S. (“Little Jack”) Horner of Virginia, who arrived in Michigan with little fanfare, and even less acceptance. Mason, and his sympathizers, let him do his thing while Mason, not-so-secretly continued to pull the shots, even though he had no official political power. A few days after Horner’s arrival, Michigan voted that Mason would be Michigan’s first Governor … assuming they were actually granted statehood this time.

Michigan, pretending to be a state, also elected John Norvell and Lucius Lyon as Senators and Isaac Crary for the House of Representatives. When the three men reached Washington D.C., however, they were not recognized and only allowed to enter the room as observers.

1836 – 1837 – The Toledo War (Finally, Sigh) Ends

President Andrew Jackson, as well as both houses of government, were finished with Michigan’s shenanigans and let the territory’s Constitutional Convention know, in no uncertain terms, that Michigan would not become a state until it gave up any claims over The Toledo Strip.

To sweeten the deal and make this decision a bit easier to accept, they also included a large portion of the Upper Peninsula to be included in the State of Michigan.

On June 15, 1836, Congress passed an act admitting Michigan to the union, on the condition that Michigan gave up The Toledo Strip and included the Upper Peninsula. Mason responded by commissioning yet another survey that he knew would “prove” Michigan’s claims over the Toledo Strip. They submitted yet another request for statehood and once again they were turned down.

By now, Michigan had another pretty big problem on its hands. Money. Or, the lack thereof.

Michigan had thrown so much money into its claim over the Toledo Strip – between funding the militia and law enforcement, and constructing buildings, not to mention paying for all those surveys and ammunition and supplies – they were discovering they didn’t have the funds for … well, anything else.

On the other hand, Ohio, as a state, had a fairly steady source of income. Not only that, but that year the United States Treasury had a four hundred thousand dollar surplus, which would be divided up and given to the States, while U.S. Territories, like Michigan, wouldn’t even see a dime. (Bear in mind that by 1800s standards, that was a ton of money.)

Finally, on the brink of both financial and political ruin, Michigan held a second convention at Ann Arbor, to discuss the federal government’s offer of statehood on the condition they gave up The Toledo Strip and included the additional land in the Upper Peninsula.

They were unhappy with this idea, but considering they had no other real choices here, they ultimately agreed.

On January 26, 1837, Andrew Jackson signs the Congressional Bill admitting Michigan to The United States.

Michigan and Ohio Today

I honestly want to say that Ohio and Michigan get along pretty well, today. Then you sit down and try to watch a football game between The Ohio State Buckeyes and The Michigan Wolverines and suddenly you’re faced with the reality that things may not have changed all that much since the 1800s.

Today, Michigan is the 11th largest state (at least in terms of land mass). But, when Michigan became a state, with the addition of the Upper Peninsula, it was the largest. And it would stay that way for roughly eight years, when suddenly “Texas” became a thing. However, in many ways, those in Michigan weren’t all that thrilled with being the largest. Sure, the majority of its state borders lay along the great lakes, but that can also be a hindrance. Just because people could use lakes like Huron or Superior for travel, that didn’t mean that all that many people were doing just that. Lake Michigan was, however, with Chicago being a growing city at the time. So, there was really no reason to build any cities or settlements along the great lakes. And, at that time, the Michigan climate made it less than ideal for things like farming, at least to any extent. Many felt like the additional Upper Peninsula, and even most of the northernmost parts of Michigan itself, was effectively useless.

That would change, however, when just as the railroad boom was in full swing, large deposits of coal and iron were found, especially in the UP. Later still, oil would be found. So, based on that fact alone, it makes one think that maybe Michigan got a sweeter deal than they had initially anticipated.

Pingback: Friday, February 6, 2026 – The Ohio Flyover