The year is 1970 and the nation is … well, it kind of all depends on who you ask. There was a lot going on to get people excited, one way or the other – from Kansas City beating the favored Minnesota at the Superbowl to the fact that nobody had figured out how to get rid of that awful disco music yet. But the one topic that seemed to get most people all riled up was … The Vietnam War.

One of the places where debates over the Vietnam War was loudest was on college campuses. At the time, many young adults felt that war was wrong, often quoting John Lennon saying “Give Peace A Chance!”

On top of that, the draft was also still a thing, so if your number was up, you could easily be required to report for duty, participate in something you felt was wrong, and as soon as you got over there, you’d learn that war was much worse than you ever could have imagined. If you were lucky enough to come home, you’d now suddenly find yourself as a symbol for a war that you wanted nothing with, taking the ire of your fellow citizens.

If Only It Were That Simple…

Kent State University was getting something of a reputation for political protests. For some, it all started in 1966 when anti-war protesters arrived at the Homecoming Parade wearing military-style uniforms adorned with gas masks. Two years later, Students for a Democratic Society and the Black United Students staged a sit-in to protest police recruitment on campuses. After they were all arrested, 250 black students walked off campus in an attempt to get them released, begging for amnesty. (It worked.)

The Students for a Democratic Society were back at it the following year, storming into an administration building where they clashed with police, many protesters would spend the next six months in jail.

1970 was already off to a wild start, including one event where protesters originally threatened to napalm a dog, only to turn it into a anti-Napalm teaching event.

A lot of historians like to lump all the college protests around this time into a single entity, as if young adults were starting to realize they held some political power, but not the wisdom or the experience to unify others into their common goals. The Vietnam War was a major focus of college protests, but other issues were making themselves known, too.

In a very similar fashion to anti-war protests, anti-police protests were becoming more common. Many college students felt that “the police” were a political force being called in to get those unruly students in line, and that line was often political. Many young adults were also starting to break from family or societal tradition, thinking that if they lived in a free society, shouldn’t they be free to follow their own career paths rather than what their parents wanted? Shouldn’t they be free to not participate in things because their elders get all hot and bothered, “You should be honored to die for your country,” one semi-famous exchange put it. “Why should I die for a country that doesn’t care what I think?” came the rebuttal.

April 30 to May 1, 1970

On April 30, 1970, President Nixon did what everybody knew he was going to do – he signed the Cambodian Incursion, effectively taking the Vietnam war to the next level by taking it into Cambodia.

In response, many students began organizing a protest for the following day, May 1st. Around noon, students began congregating in the grassy knoll in the center of campus, and soon an estimated five hundred students were present. Beyond that, not much remarkable happened … a few students buried a copy of the United States Constitution, calling this a symbolic gesture based on how they felt Nixon had already killed it … Another student hung a sign on a tree that asked why the ROTC building was still standing.

As they were leaving, they thought “that was fun – we should do it again.” “Sure, how about the day after tomorrow, give us a little more time to organize.” “Can’t do it on the third, I’ve gotta wash my hair. How about on the 4th.” “The 4th is good for me, I’ll see you then.”

(Ok, you got me – that conversation never happened. But, the protest on the 4th certainly did.)

By the time it started getting close to 1:00pm, the students started to disperse. The protests were over and they had to get back to class. Later that evening, the Black United Students held a similar protest where 400 black students likewise gathered in solidarity.

Meanwhile, in Washington, The President isn’t helping things. After someone from The Pentagon mentioned that the war expanding into Cambodia made her proud to be An American, the president issued the following response:

“You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses. Listen, the boys that are on the college campuses today are the luckiest people in the world, going to the greatest universities, and here they are burning up the books, storming around this issue. You name it. Get rid of the war there will be another one.”

Needless to say, The President’s words didn’t go over well with university students, once again being slighted by those with the most political power. This unrest could be felt all over the nation, not just with Kent State, but what was happening there started to get the authorities very worried.

May 2-3, 1970

The students in Kent believed that if the president was going to (all but) declare war on them, they were going to do the same. Businesses around town began reporting that they had received threats telling them that if they didn’t’ display anti-war posters, their buildings were going to be burnt to the ground. There were some minor riots about town, but nothing that hadn’t been seen before (or since).

The Governor of Ohio went on record calling Kent State students “Unamerican” hell-bent on destroying educational facilities in Ohio, and comparing them to various groups, such as the Nazi “brown-shirts” … and all but forbidding them from holding any further political or protest rallies.

At the same time, many of the protesters who saw the carnage the little riots were having organized into smaller groups, descending on the downtown area and helping with the clean-up efforts. They wanted to be sure that people were aware that not all the protesters were rioters, that was just a small fringe group of opportunists. Political protest was one thing – vandalism and riots directed toward businesses were something else altogether.

It is worth nothing here that while some of the local businesspeople welcomed the students help with cleanup, others did not. They accused the students of being the problem, saying that they didn’t trust that their motives were good.

Later in the afternoon, the Governor openly discussed calling a “state of emergency” which he believed would completely curtail any and all political protests, although he never actually went through with it. The only person to officially act, however, was Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom who issued an official curfew, effectively immediately until further notice.

That evening, protesters started to gather again on campus but was soon met by The National Guard who used tear gas to disperse the crowd. They then went to the corner of Lincoln and Main, attempting a sit-in with hopes of forcing a meeting with the mayor, the governor, and the University President Robert White. Again, they were met by the guards who informed the students of the curfew and demanded that they return home. While some did exactly that, others stayed and were promptly arrested.

Monday May 4 1970

The original plans for the rally that had been made several days prior was to meet on campus around noon. In an attempt to cancel the event, University administration printed and passed out fliers stating that the rally had been cancelled. Even with those efforts, most estimates say that about 2,000 protesters gathered somewhere on campus.

At approximately noon, someone rang the “Victory Bell” – normally the bell would only ring during home football games whenever Kent’s team scored, but it rang that day, too. As soon as that had been done, someone got up in front of the gathering crowd and spoke.

So far, everything that day had been peaceful.

What happened next would be debated for years to come.

Shortly after the first speech, the Ohio National Guard attempted to disperse the crowd, although it would be years before it was determined whether it was legal or not for them to do so. Even though the guard had a bullhorn, the students were making such a noise that it was hard to hear anything being said.

The head of the Campus Patrol then got into a National Guard Jeep and tried shouting at the crowd, demanding that they leave. The protesters responded to this by using rude gestures or beginning to sing protest songs.

One student reportedly threw a rock at the Jeep, but it caused no damage. So far, other than that, everything had been peaceful.

Ramping things up a bit, the National Guard tried again to get everyone to leave by using tear gas. This, however, was not a well-thought-out plan, as the M79 Grenade Launcher misfired sending the projectile only a few feet. A few grenades were easily picked up by students and thrown back at police. Also, it was something of a windy day, enough so that the tear gas was rendered mostly ineffective anyway. Just about the only effect this had on the crowd was to make them angry and start chanting something about how the pigs should get off the campus.

Again, the Ohio National Guard was issued an order to advance. Using tear gas effectively this time, and one unit was ordered to fire their guns into the air, they managed to drive students away from the quad but wound up boxing themself into some practice fields. It was clear they did not know the layout of the campus, nor had they a plan of where to go and exactly what to do.

Now there were several spots on campus with smaller groups of protesters throughout the campus. According to FBI records, there were a group of about 10-50 students on top of a hill, throwing rocks at the National Guard.

As Troup G was preparing to exit the practice field, they were given the order to drop to their knees and aim their weapons toward a parking lot where a growing group of protesters were assembled. A guard, we’re not totally sure who, fired a handgun into the air. An order was given for the guards to regroup at Taylor Hall, but they were followed by a small group of protesters.

It was at this moment that shots would ring out.

4 Dead, 9 Wounded

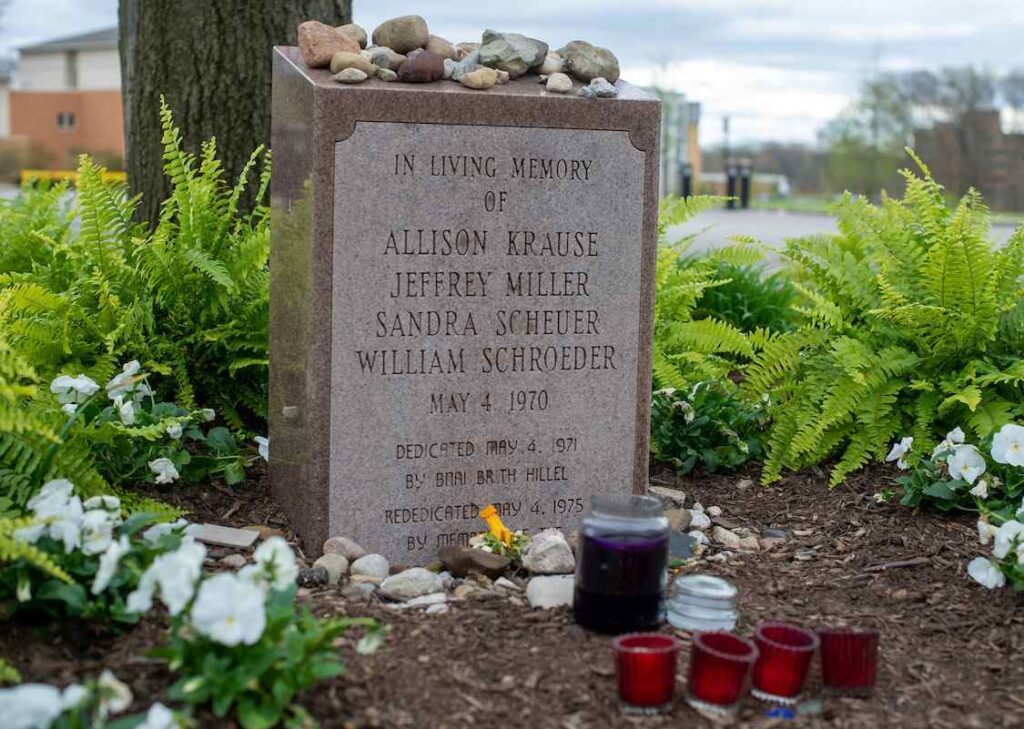

At 2:24 PM, on Monday, May 4th, 1970, four students (Jeff Miller, Allison Krause, William Schroeder, and Sandra Scheuer) would all lose their lives.

An additional nine students (Joseph Lewis Jr., John Cleary, Thomas Grace, Alan Canfora, Dean Kahler, Douglas Wrentmore, James Russell, Robert Stamps, and Donald MacKenzie) would be wounded.

…all from gunfire from the Ohio National Guard.

It would take many years before we had a full and mostly complete understanding of what, exactly, happened … and who, ultimately, was at fault.

From an unnamed witness quoted by United Press International, Inc:

Suddenly, they turned around, got on their knees, as if they were ordered to, they did it all together, aimed. And personally, I was standing there saying, they’re not going to shoot, they can’t do that. If they are going to shoot, it’s going to be blank.

From another unnamed witness:

The shots were definitely coming my way, because when a bullet passes your head, it makes a crack. I hit the ground behind the curve, looking over. I saw a student hit, he stumbled and failed, to where he was running towards the car. Another student tried to pull him behind the car, bullets were coming through the windows of the car.

From yet another witness:

Then I heard the tatatatatatatatatat sound. I thought it was fireworks. An eerie sound fell over the common. The quiet felt like gravity pulling us to the ground. Then a young man’s voice: “They fucking killed somebody!” Everything slowed down and the silence got heavier. The ROTC building, now nothing more than a few inches of charcoal, was surrounded by National Guardsmen. They were all on one knee and pointing their rifles at … us! Then they fired. By the time I made my way to where I could see them, it was still unclear what was going on. The guardsmen themselves looked stunned. We looked at them and they looked at us. They were just kids, 19 years old, like us. But in uniform. Like our boys in Vietnam.

That was from Chrissie Hynde. You may have heard of her, she later went on to be the lead singer of the rock group The Pretenders. And then there is this, from Gerald Casale, the lead singer of Devo:

All I can tell you is that it completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew. Two of the four people who were killed, Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause, were my friends. We were all running our asses off from these motherfuckers. It was total, utter bullshit. Live ammunition and gasmasks – none of us knew, none of us could have imagined … They shot into a crowd that was running from them!

I would say that nothing like this had ever happened before, but that wouldn’t exactly be true. We still have to ask…

Why?

How could such a thing happen? Why did the National Guard fire on what unarmed citizens, college students, as they were trying to flee.

In the months after the Kent State Shootings, how you attempt to answer that question kind of depended on politics. Or, at least, what you thought about the Vietnam War (or war in general).

When the various members of The National Guard were questioned, many (most) of them claimed that they feared for their lives, claiming that they were surrounded by violent protesters; some claimed that they were shot at first, either by the protesters, by individuals throwing rocks, or by an unknown sniper.

There were a few problems with this. First off, the number of students throwing rocks was, even by their own admissions, relatively small. Most accounts claimed approximately ten people while a few others suggested no more than fifty. Either way, out of two thousand protesters, that’s not a lot.

Likewise, there was no physical evidence that a sniper even existed, or that the guards were even shot at. (Let’s face it – those bullets would have hit … something, right?)

Perhaps most damning of all is that none of the students shot were all that close to the National Guard. The nearest of the students who were killed was Jeff Miller, 265 feet away – the farthest, Sandra Scheuer was 390 feet away. (Just to put that in perspective, that’s nearly a full city block in most cities.)

The victims were also running away from the guardsmen, so at that distance – it’s really hard to claim self-defense.

A few of the National Guardsmen claimed that they either assumed that a fire order had been given, or they claimed to have heard one, even though no such order had been issued.

Still today, as it was in 1970, often how people saw the Kent State Shooting depended on their political views, their politics, or their opinions on the Vietnam War or political protests.

On one hand, the now dead were innocent (or at least unarmed) citizens who didn’t deserve to die because they disagreed with the political position currently holding power. They were college students and should have at least been a little protected, someone should have kept them safe. In America, you have a right to political protest – it’s in our constitution. Yes, a small number of protesters did get violent, and maybe some were pelting the “authority” with rocks, but wouldn’t lethal force be a bit much? Let’s also bear in mind that many of The National Guards men who were there were just teenagers, just like they were, and it’s safe to assume that they didn’t have the training for this type of scenario.

On the other hand, the fatally shot students were part of a mob which had a recent history of turning violent and the national guard simply had to display a show of force before things got out of hand. If you do not support the actions of your elected government, that is un-American, pure and simple. Going off to war should be a rite of passage, a duty of every American – it is the price of freedom.

How History Records This

I do not know of anybody who says that killing four college students as (or during) political protest is a good thing. However, even today, there are those who look at Kent State and stand either fully behind the protesters, or fully behind the actions of the Ohio National Guard. This echoes other situations in America, with or without fatal shootings by law enforcement or troops somewhere on the military’s spectrum.

Today, the official version is that the entire situation was nothing more than a huge confusing mess. The Ohio National Guard should not have fired upon students, especially not ones running away from the gathering. They never got an order to shoot, we’re pretty sure of that now. Yet, they were in a precarious position, unsure of which aspects of their training they should have relied upon, how they should have viewed the entirety of the situation.

As if they are not at fault.

Yet, many of these same themes are still echoing through the halls of history in the present political landscape. Just look at “Trump vs. The Democrats” or ‘ICE vs. The Undocumented” … and I fear that history is primed to repeat itself.

Clearly, both sides have learned some lessons from history – while simultaneously making it look like no sides have learned anything at all. It seems like it’s more about learning from the past to make your side more victorious in the future. Couldn’t we, instead, look at situations like this and ask ourselves what we could have done to prevent this kind of situation from ever happening again?