The year is 1865 and the streets of Cincinnati have a problem. To be fair, they have lots of problems, between the rodents scurrying about and the number of drunks passed out and laying in their own … um … filth, let’s just say that residents certainly had a number of things they liked to complain about.

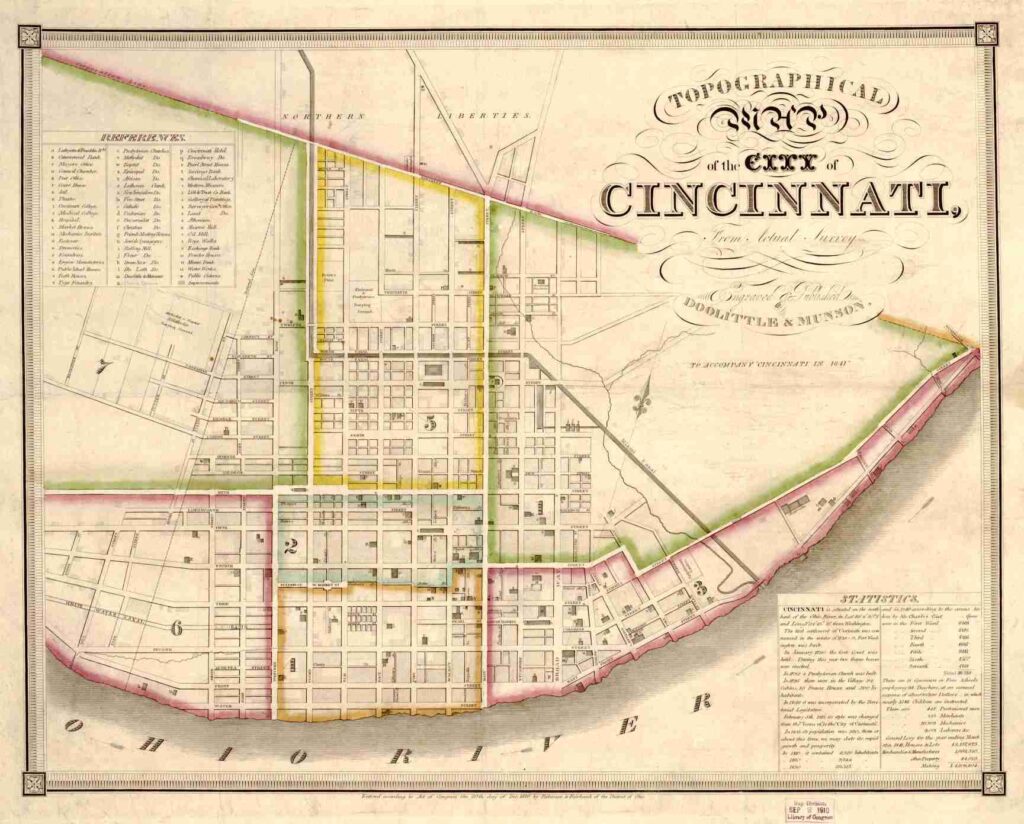

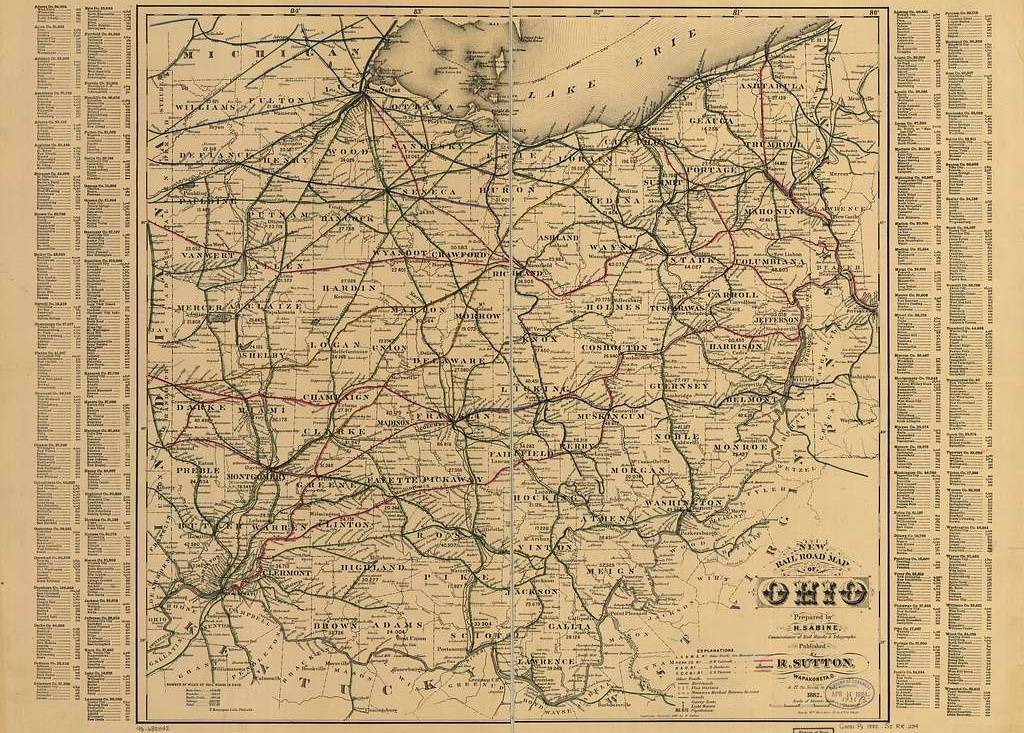

Some of Cincinnati’s problems probably came from the fact that the city had grown a lot more than anyone a hundred years previous had anticipated, and apparently none of the early planners had bothered to consult a psychic to foretell the city’s future.

Also, during this period of history, a lot of things around the world were changing with new technologies and better ways of doing things – and it was not just Cincinnati that was having a problem keeping up. And, at this time, they were on their way of becoming one of the biggest cities in the United States.

Part of the problem with the Cincinnati streets is that they made no sense and since everyone at the time was refusing to use Apple or Google Maps (since, technically, they hadn’t been invented yet) it was hard to get around, and sometimes it was hard to find the place you were looking for.

Let’s say that Aunt Irma bought a house on Plum Street between 2nd and 3rd. (This was, of course, before the days of I-71 being there since nobody owned cars yet, so let’s just go with it.) Now, chances are none of the houses in town had numbers on them because when the house was built, nobody thought they needed them. Everyone knew each other, and if you wanted one particular house as opposed to any others, you have to give further details. Then, of course, you go to Aunt Irma’s house and realize that the “white house with an elm tree in the front yard” could be one of three possibilities, so … um … ??? UGH!

Some addresses did have numbers, which apparently were assigned at random. So, it was possible that one block might have address numbers 521 and 643 and on the next street over the same block might have 844 and 133.

That is why, in 1865, Cincinnati’s city council decided to number street addresses and in order to do this, they also had to pick a spot where the numbers would begin. At the time, this was no easy feat.

For streets going north and south, the city’s natural boundary of the Ohio River was chosen because that made the most sense. Therefore, the first building north of the river would get an address of 1 and the numbers would go up from there.

This really did nothing to clear up any confusion mostly because the Ohio River does not form a straight line. Therefore, an address of 465 on one street might be 412 one block over and 383 on the one after that.

Another problem with this first way of numbering addresses is that not all streets were the same size. And some of the bigger streets had a lot more things to number than smaller streets, which caused quite a bit of even more confusion.

Streets going east-west had a different problem as there was no distinct natural landmark that could be used to start numbering. Some people believed that either Elm or Vine Streets should be designated as they felt they were more geographically center, at least a little farther away from the river. However, Main Street was chosen partly from its history (it was among the first “big” streets in Cincinnati), partly because it was slightly larger at the time than Elm or Vine, and partly because it had more addresses on it. So, anything East of Main Street would have an “East” address, and anything west would have a “West” address. Also, for the first block to the east or west of Main Street the numbers would start with 1.

One of the larger issues on the east-west streets is that not all buildings were the same size or the same shape. So, you might have two very narrow buildings next to a very wide one, so how is that going to effect numbering? It also didn’t address the issue of what to do if one address was on top of another address (as in, ground floor had a storefront with apartment living above – so does the building get a single address to share, or does each thing get its own.

This new system was a good start – but it did little to clear up the confusion and in the process it actually created a lot more.

A Second Try

In 1891, City Council tasked two men, Charles Wuest and M.B. McIntyre, to devise a system that was less confusing. Both men liked the general idea of the 1865 plan, but perhaps there were some ways to improve upon it.

Their major contribution to the solution was in block numbering (the first block from the baseline would start with the number 1, the second block would start with 100, the third block would start with 200 and so on – pretty much what we have today) … and they also required that each building’s address to only be on one street.

Part of the confusion of the earlier system was that many buildings bordered (or even faced) two separate streets. A lot of the alleys also had street names, and there were also a lot of smaller streets that have since been wiped off the map. They weren’t roads like Main Street or 4th Street, but they ran (at least partly) between them. A few of these do still exist today, such as Ogden Place or Benham Alley.)

Also, they decided that Main Street, not being in the center of town, shouldn’t be used as the baseline street, so they changed it to Vine.

This system was not entirely perfect as it did not address the named alley or smaller street issues, but it gave the city a uniform system to use and that, once implemented, would clear up any and all confusion.

Once again – there were major problems that nobody foresaw, even though some of them they probably should have. For example, while the city council wanted to come up with a new plan, what they didn’t do is figure out how to pay for it. It took them a few years to get around to that, but they eventually did exactly that.

Another issue they suddenly faced was that homeowners were partly confused as to what their actual address should be … and many were also upset that their address seemed to be constantly changing. They advertise their business is at 421 Whatever Street, then it’s 411 Whatever, then 391 Whatever and how the heck are people supposed to find them?

In all this confusion, a further problem arose – charlatans. In the years between the City Council approving the new address numbering system and the time they finally got around to funding it – some of the city’s more unscrupulous citizens saw an opportunity to make a quick buck or three.

When city employees finally started going around to addresses to help them fix the posted addresses, they were quick to hear from many building owners that they had already changed their addresses to the new system, even though the posted addresses were (still) incorrect. This involved them paying fines as well as purchasing number plaques to comply with the city’s other new address requirement: that the addresses of all buildings had to be visible from the street. They weren’t all that happy to learn that they had to buy new numbers to put on their buildings, but also update their addresses yet again.

Some owners refused to comply with the new orders, firmly believing that the person who had contacted them years before was the true representative of the city and not those whose job it currently was.

Third Time’s The Charm

If you look at old newspapers from between 1895 to 1898, you’ll start to realize just how slow this process had been. By the end of 1895, only a few addresses close to the Ohio River had been updated (or assigned addresses), and by 1896 the changes had only reached about 10 blocks, with five or six blocks being done in the following year (which was the year they finally got around to funding the new system, so that helped speed things up, too.) You’ll see the address changes more in advertisements than anything else.

One newspaper, The Cincinnati Post, decided to try and get in on the craze in their own way, too – by producing their own number plaques that residents and business owners could use to display their addresses. One other private company decided to try and put their own spin on the issue, too. If clocks now had numbers that glowed in the dark, why not do the same for street address numbers?

Beyond the funding issue (and the scammers who took advantage of the confusion) this new system still was not perfect. City leaders seemed more upset now than ever, and were on the brink of throwing the entire thing out the window and trying again.

But, luckily, they came to their senses and rather than devise yet another completely new system – they just addressed the flaws and oversights with the current one.

For example, what to do with buildings with entrances on more than one street (such as buildings on corner lots or buildings that went the entire length of the block). This is also when odd numbers started to appear on one side of the street, even numbers on the other. So, that kind of helped a lot, too.

A Historical Reminder

Even though cities and towns can (and do) use different address numbering systems, most of the basic ideas are relatively standard – odd numbers on one side of the street, even numbers on the other, no more than one hundred address possibilities per street block, and the numbers on one side will align (more or less) with the numbers on the next street over. (Yet, somehow Aunt Erma still manages to get lost.)

But, it’s important to remember, especially when doing things like “history” or “genealogy” that this wasn’t always the case. You may be browsing through historical records and suddenly disover that some home or business went from being at one address to another and you may be tempted to think they relocated – when in reality it was only the address that had changed.

Street names can change, too, though. So, maybe the bottom line here should be something about making assumptions and being open minded to alternative possibilities.

Pingback: What Horrors Lurk Under 1313 Vine Street, Cincinnati? - The Ohio Project