If there was one thing I’ve learned about Ohio that has surprised me, it is its history regarding alcohol.

What I seem to remember from my school years is that the 1920s was a rip roaring good time, until that prohibition happened, and everyone got upset. Prohibition backfired because it ultimately led to organized crime, so in 1933 the 21st Amendment suddenly became a thing and prohibition was over. Unfortunately, organized crime was not, and it continues to be a problem to this very day. As for alcohol, it was legal to buy and sell everywhere, as long as everyone was old enough (and as long as it isn’t a Sunday, at least in some of the towns I’ve lived in).

The more I study this … among other subjects … I’ve come to realize that this version of history isn’t exactly accurate. And, for the state of Ohio … it’s actually quite a complicated story.

The Birth of the Temperance Movement

By most accounts The Temperance Movement (aka, the Anti-Alcohol Movement) began sometime around 1800, or a few short years before The State of Ohio became an actual thing. Although, to be fair, the idea behind the movement had already been around for quite some time. For example, in 1737 French-Canadian-Shawnee tribal leader Peter Chartier (of the Pekowi Turtle Clan) tried to forbid the sale of Rum to members of any indigenous tribe, and after that seemed to fail, he begged Governor William Penn for help. Penn did pass some new laws, however they weren’t enforced very well, and alcohol abuse among indigenous people kept getting worse.

Along this same time, over the pond in Great Britain, a new drink was all the rage – Gin. Because it was affordable to even the lower realm of the middle class, public drunkenness became a national debate. In 1743, John Wesley, the guy who founded the Methodist Church, proclaimed the evils of alcohol, telling anyone who would listen that it was best to just leave the stuff alone. It didn’t take all that long for many other churches to start saying the same.

Like many social movements, The Temperance Movement wasn’t started by a single individual sticking his head out the window and proclaiming “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” Instead, it started with a number of individuals and smallish groups, each trying to do their own thing. However, it wasn’t until the 19th century that many of these smaller groups started to organize among themselves, drawing in more sympathizers with every passing year.

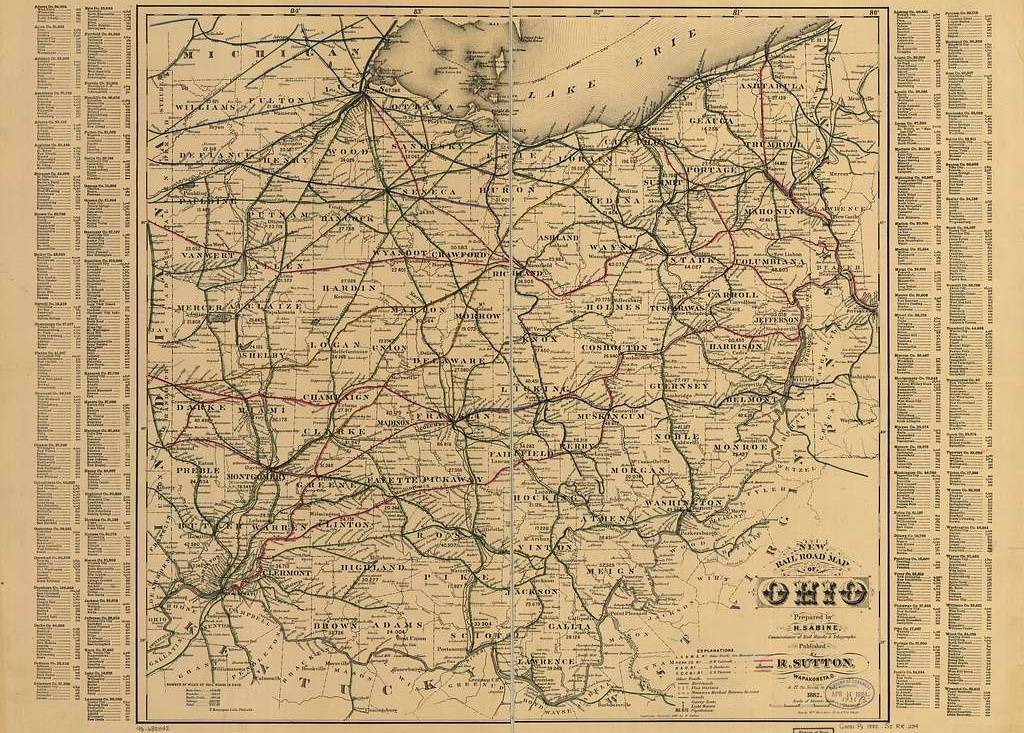

Around the turn of the 19th Century, the national landscape was rapidly changing, too. For example, in 1803, Ohio became a state. And, as New States tended to do, land was split up and sold to people who wanted to live or work there. New communities were formed (or relocated from somewhere else). Some of these communities were based on the geographical origins of the settlers, for example, a group of Dutch settlers came over, picked a spot, and declared it “New Holland”. Other communities centered around local geography, such as the mining communities which at the time dotted the Appelatians. But, quite a few were based on the philosophical or religious ideals shared by the settlers.

Alcoholism at the time was seen as a moral problem, as opposed to a psychological or physical one. At the time, nobody knew about addiction or chemical dependency, all they saw was some dude grab a woman’s butt and then throw up in the corner while some other dude tried to pick a fight with as many people as possible. These were things that good, decent, moral people just didn’t do, so clearly alcoholics were just immoral buffoons (my apologies to any actual buffoons who may be having this read to them) who needed a slap of morality across the face. Anyway, it should come as no surprise to realize that the largest forces behind the new Temperance Movement tended to stem from the more religious communities, or at least the churches in more secular towns.

The early 19th century also saw the Second Great Awakening, or a sudden increase in Protestant reforms and the spreading of religious ideals through the “new country”. While most will argue that the roots for this were the states of Kentucky and Tennassee, the Ohio area saw its fair share, too. And, along with this came the message from the pulpits that alcohol consumption was bad, well, except maybe for that Biblical thing where Jesus turned water into wine, but we aren’t going there.

Temperance might not have been the main focus of this Great Awakening, but it certainly went hand in hand, although The Temperance Movement wasn’t associated with any one particular church or denomination.

Just like these various religions couldn’t agree on religious ideals, they also couldn’t agree on what, exactly, temperance meant. For some, it meant not consuming alcohol to the point of intoxication. A little bit here and there was okay, but if anyone could tell you were drunk, that was bad. For some, it meant no alcohol, period. No beer, no hard liquor, and no wine, not even Jesus wine (except, maybe for communion, but let’s switch to grape juice and just call it wine because … reasons.) For others, Wine was fine, at least in moderation, and beer and spirits were bad.

Still, the one thing most everyone seemed to agree on was that nobody felt like they should have to deal with that drunken bastard stumbling down the street, peeing in the bushes, and trying to fart The National Anthem. Yeah, that sick bastard had to go.

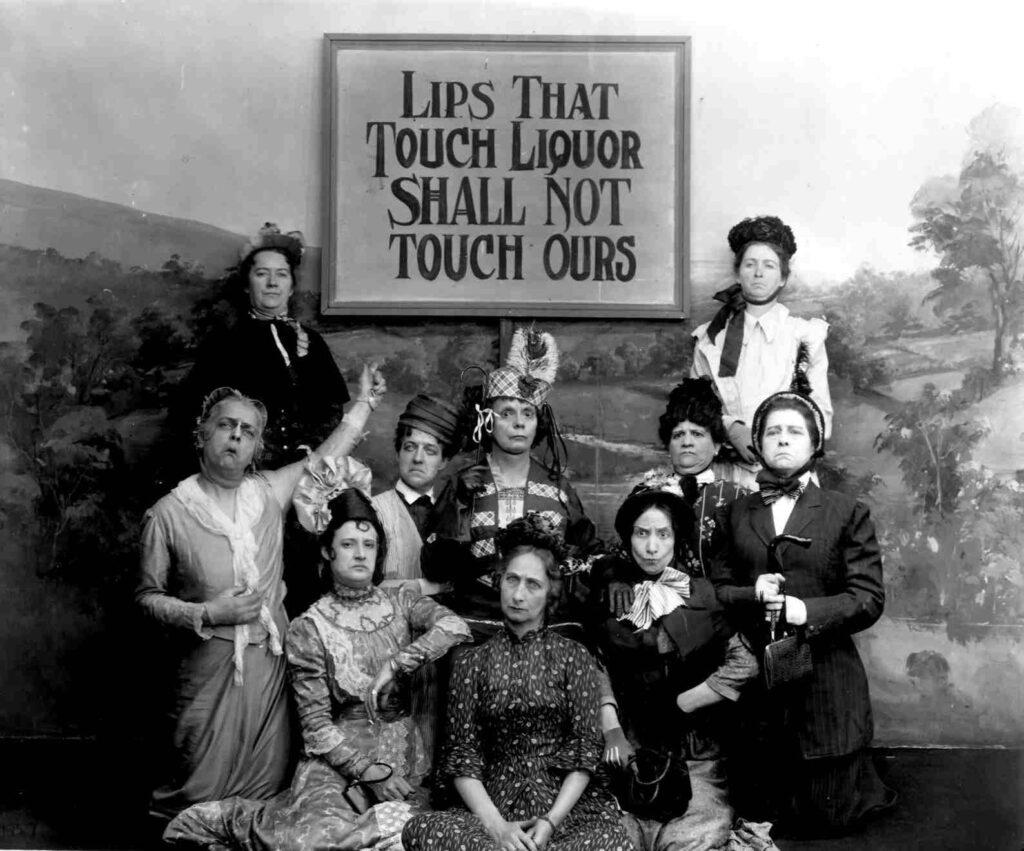

The second half of the 19th century finally saw a few organized (or sometimes disorganized) groups getting formed. Many of these were run, at least in part, by women – and it isn’t like they had the ability to vote yet. Many were organized through various churches or social groups. Others, not so much. For example, in Baltimore the Washingtonian Movement started by men, outside the churches, taking a more sympathetic approach to alcohol abstinence.

Ohio’s Eliza “Mother” Thompson

On December 23, 1873, Eliza Thompson attended a lecture by Dr. Dio Lewis on the subject of temperance (and, supposedly, homeopathy). During the lecture, Dr. Dio suggested that people should protest at places that sold alcohol, and Thompson, being one who didn’t like to sit idly by, decided to do just that. But, she knew that she couldn’t do it alone. On December 23, 1873, she set up a meeting at the local (Hillsboro, Ohio) Presbyterian church and formed a committee of at least fifty people. They were able to raise a reported $12,000 (which is an insane sum at the time) to help the cause.

That Christmas, a group ranging between 75 and 115 women marched from the church to four local drug stores that sold alcohol. At the first two, they found success, being able to convince the owner to stop selling any kind of alcohol. But, at the third, they were met with resistance. The owner threatened to have the women arrested for trying to interfere with his business, suggesting he may sue them for trespassing and damages. Eliza and her entourage prayed outside the business and moved on.

The following day, the group again met at the church, this time marching to the local saloons. Each time the group was met with success, it seemed to energize the ladies, as if they were on the right track. When they were met with resistance, they took it as a call to work a bit harder.

Mother Thompson’s work on temperance first caught the attention of the locals, but before long her name and her story became national news. She organized groups not just in her hometown, but in nearby towns like Washington Court House approximately 30 miles north. It was these groups that helped both the National Temperance Society and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) grow by leaps and bounds.

In 1881, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union successfully petitioned the legislature to mandate teaching what they referred to as “Scientific Temperance” – teaching all public and military schools about the harmful effects of consuming not just alcohol, but also illegal drugs and tobacco.

The Anti Saloon League

In 1893, a group of Temperance supporters got together in Oberlin, Ohio and formed The Anti Saloon League. Meanwhile, a group in Washington D.C. were doing the exact same thing. While the two leagues were similar in their beliefs, they didn’t have all that much to do with each other. But, we’ll get to that in a moment.

According to the Ohio Anti Saloon League, America was in a moral decline as more and more people moved from rural to urban communities. One of the biggest signs of this religious decline was the growing number of bars, taverns, and saloons. God, they believed, didn’t want anyone to consume alcohol, and if the Nation wanted to stay in His good graces and have periods of prosperity, then all the booze had to go (or, at least, slow the fudge way down).

Just as Churches, to them, stood for everything good and God-like, Saloons stood for everything ungodly and evil. And by God, those places had to go.

While groups like the WCTU and other Temperance Organizations focused more on the individuals, The Anti Saloon League wanted to play a bit differently. They wanted existing laws to be enforced better, and they also pressed for new laws, often with harsh penalties for those who break them.

The ASL never aligned itself politically with one candidate or the other, opting instead to focus on the individual candidates or politicians. So, in one town, they might be supporting the Republican mayoral candidate, and in the next town over throwing support for the Democrat – it all depended upon how the individual viewed Temperance.

Two years after forming, the Washington D.C. Anti Saloon League, and the one from Oberlin, Ohio got together and thought they might have a better outcome if the two groups joined forces. They did exactly that, and soon the American Anti Saloon League opened in Westerville, Ohio.

The AASL believed that to better get their word out, what they needed was a printing press, so they went and got one. Soon, the first edition of The American Issue was published. As you could probably imagine, every headline was informing readers where Temperance issues were on the ballot box (and how to vote), or presenting news stories with headlines such as “Liquor traffic exposed in attempt to profit from GRIP epidemic” and “With saloons closed during GRIP epidemic, arrests down 80%” and “Alcohol Not A Medicine” (all from the November 1, 1918 publication).

Other than publishing the American Issue, they also created and distributed tracts, small books or pamphlets that carried the “alcohol is bad” message in one form or another.

The AASL had moderate success in passing laws and backing candidates sympathetic to their cause, at least until they finally got what they wanted: Prohibition. Once alcohol was essentially outlawed, many of their supporters felt there was nothing left to fight for, so the group’s social and political influence dwindled. So, by the time Prohibition started to backfire big time – there was nobody left standing to do much good.

1920 – Prohibition

In January, 1920, the enactment of The Volstead Act and the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, brought about a new era in American History – Prohibition.

Now, most (but not all) forms of alcohol were … banned. An exception was made for wine for use in religious services, and there was no federal law banning the private ownership and consumption of the stuff. Many states made up for this by passing their own laws prohibiting any use of alcohol, except maybe for Church Wine or Medicinal Alcohols. Or, maybe not.

During prohibition, one of the major issues of contention was essentially the medical use of alcohol. After all, if a doctor prescribed it, then anti-alcohol laws couldn’t touch you, right? Unfortunately, the debate into the medical use of alcohol was overshadowed by fraud. Many doctors and pharmacists quickly learned that some people would pay top dollar, not just for a doctor to say it was medically necessary, but for the pharmacist willing to sell it to you.

In fact, one of the worst kept secrets was how Charles R. Walgreen expanded his small operation of about 20 pharmacies to well over 500 during Prohibition. (I won’t tell you the name of the pharmacy, but I bet you can figure it out. Wink wink nudge nudge)

So, passing a law like Prohibition was one thing – enforcing it was something else, entirely.

While most of the American population at the time abided by the new laws, not everyone was happy about it. And, I have to admit, there was a fairly large number of people who really couldn’t care one way or another. For those who really wanted their boose, they were bound to get it one way or another. And, any tavern or store that would sell the stuff, they quickly discovered that those people were going to pay very well indeed.

While the rural areas were suddenly faced with moonshiners, or those who produce alcohol on their own, for their own consumption or to sell to “friends” … that wasn’t going to work very well in the more urban areas. For the perfect example there, we just have to look at a certain bar owner in the Chicago suburb of Cicero.

To be fair, Prohibition didn’t make Al Capone, as he was already well on his way to mobsterhood, but prohibition did, at least, help define him and it helped bring organized crime into what it is today. Capone (either on his own or with help from his henchmen) not only set up hidden areas inside his establishments, not just for the consumption of alcohol, but also for other slightly illegal activities like gambling. The problem was, if he got caught, it wasn’t just that he might get in trouble – the big issue is that the police might find a way to shut his place down. This he solved by a multi-pronged approach.

First off, his speakeasies were fairly well hidden, but they also contained an elaborate system where if the police did happen to show up, the booze wasn’t easily found, and it could quickly convert to something else, or a hidden tunnel could take patrons who didn’t want to face the law could easily escape into the night. Secondly, he bribed the police, the mayor, and a few other miscellaneous politicians to leave him alone. (I know, Chicago cops and politics … corrupt … who’d have known?)

The thing was, though, that everyone knew exactly what Al Capone was doing (and most people knew how he was doing it). The Chicago Outfit (let’s call it what it was, a gang) was more than just illegal alcohol sales and backroom gambling. This dude had his hands in so many things it’s actually a wonder he knew everything he was doing (or, having done).

Capone ran the Chicago Outfit for seven years. (I know, it feels like it should have been a lot longer, all things considered.)

Prohibition in Ohio

Urban Communities

In the larger urban areas, Prohibition existed in much the same fashion as discussed above in Al Capone’s Chicago. I suppose the main difference was that the mob was a bit smaller. (Except, maybe in Cleveland.)

In places like Cincinnati, with a large German population, when the first World War broke out, many people defended prohibition not on moral grounds, but anti-German. (Look at those German fools wanting their German beer…See the prohibitionists were right all along.)

During prohibition, many taverns began tunneling underground as a place to store their alcohol, away from the eyes of law enforcement (and, I have to assume, other tavern owners since alcohol was suddenly a hot commodity). However, people quickly discovered an unintended benefit to keeping their booze underground. Even on a hot summer day, these caves were cool and mostly dry – ideal conditions for liquor storage. Even after prohibition ended, many taverns continued to store their stock in these underground cellars and caves. In recent years, at least one pub in Cincinnati now offers tours through one of these caves. Although it’s existence may have started during prohibition, its use did get slightly modified in later years.

Speaking of Cincinnati … while Chicago had it’s Capone, Cincinnati had its Remus. As in, George Remus. The Bootlegging King.

Like our Chicago pal Al, George owned a few taverns, some gambling halls, a few bordellos and brothels, and a few other various establishments throughout the Cincinnati area. Unlike Capone, however, he lacked that old fashioned mob mentality. So, no deals with police, only a few with local politicians, and this would eventually lead to his downfall. But, we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

If there was one other thing George was known for – it was his lavish parties. In fact, the Great Gatsby character in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel is said to have been mostly based on him (and a few others for good measure). In one documented party, all male guests were given Diamond studded pins as a parting gift. Yeah, kinda wish I had been there. In another party, he gifted each female guest a car. (So, take that, Oprah!)

George Remus ran his criminal empire in Cincinnati until he ultimately got caught and charged with over two thousand counts of violating the Volstead Act. Oops. He was then sentenced to a two year prison sentence.

While in prison, Remus befriended what he thought was an inmate, but in reality was a Federal Agent named Franklin Dodge. Remus confessed that his wife, Imogene, had control over all his money, saying how they had stashed away a small fortune. However, rather than report this information back to his employers, Dodge instead opted to search Mrs. Remus out for himself. It is unclear whether he fell in love with her, or her bank account, but soon the two were having a torrid affair. Imogene filed for divorce. Behind bars, George didn’t have access to any of his money, or the power associated with it. In the end, Imogene allowed her husband to keep roughly one hundred dollars of the green foldy stuff while she and her new beau, Franklin, were rolling in the stuff.

After an unsuccessful attempt to have George Remus deported, they then hired a hitman to kill the guy. However, this guy reported what was going on to George, and ran off with the $15,000 he was paid for the dirty deed never to be seen around Cincinnati again.

Six months after being released from prison, George Remus tracked his now-former wife down in Eden Park, forced her car off the road, and much to the horror of onlookers, shot the woman to death. At trial, Remus claimed temporary insanity, citing the wife’s betrayal and pointing to Dodge as the true villain of the story. The jury acquitted him, and the state reprimanded him to a psychiatric facility where he would live for the next seven months. Following this, George Remus seemed to have lived a fairly unremarkable life until his death, some twenty years later.

Up in Cleveland, corruption within the police and political circles was running rampant. Illegal taverns were being run pretty much the same way as everywhere else. However, in this case, you also had imported liquors making their way across Lake Erie from Canada. In cities like Cincinnati, Columbus, and Cleveland, various forms of “medical alcohol” were being distributed in various ways. One common example popular in Ohio included something called “Jake” or Jamaican Ginger, containing just under 80% ethanol by weight.

In small doses, it was a remedy for anything from excessive flatulence, headaches, menstrual problems, and respiratory infections. In larger doses, well, like I said, it was 80% alcohol. And it was available freely over the counter, no prescription needed.

In the mid-1920s, the way Jamaican Ginger was produced changed a bit. Rather than use castor oil, which was becoming more expensive, a different substance was used instead. With this change, the ethylene and diethylene glycols were out, and a new substance, Tricresyl phosphate was used instead. The problem was that this was a rather potent paralytic agent that attacked the spinal cord, causing various levels of irreversible paralysis in the legs and feet. For some, this created a pronounced limp. Others saw a complete loss of function below the beltline. “Jake Leg” (among other nicknames) was a relatively new problem.

The other foreseeable consequence for the sudden rise in Jake production is that manufacturers sometimes cut corners. Other times, the manufacture process was flawed in some other way, but the results were the same. In one month alone, over 150 people in Cleveland and Cincinnati alone died as a result of Jake Poisoning which was linked back to a manufacturer in Buffalo New York.

Rural Communities

The idea behind prohibition tended to go over better in rural areas and the smaller towns. Quite often, these areas tended to be more religious (or, at least on Sundays) and when the Church is the big social gathering place near you, and the church is preaching against ungodly vices like gambling, prostitution, drugs and alcohol, then they certainly gave the appearance that they were just fine with that whole prohibition thing…

But, were they really?

Well, yes, in many rural areas, they truly were. But, in others – moonshine turned out to be the key.

After working long, hard hours in the mines, or after spending countless hours in the sweltering sun doing farm work, all Papa wanted was to come home, eat some dinner and have a few drinks before heading off to bed to do it all again the next day. (Bear in mind, also, this was a time before current labor laws went into effect, so working ten hour days … working six or sometimes seven days a week wasn’t all that unheard of.)

Many rural residents instead chose to take matters into their own hands. If they couldn’t get some pints at their local general store, they’d just have to make their own. The ingredients were easy enough to get and it wasn’t all that hard to create your own distillery in your basement (or in your bathtub). The only thing that wasn’t easy enough to do was make it taste good. But, I suppose if you’re bound and determined to get drunk, you won’t let something like that stop you.

The End of Prohibition

There wasn’t one person or thing that ended Prohibition, there were a number of factors that went into it. As America was entering The Great Depression, the national cost of enforcing The Volstead Act seemed irrationally high. Prohibition was also the biggest contributor in the development of modern organized crime and it was hard to fathom how law abiding citizens were struggling while the criminals were raking in the dough. And, when you get down to it – Prohibition didn’t work nearly as well as they had hoped. There were just too many loopholes in the system. But, at least I guess, the number of people falling down drunk in the middle of the sidewalk decreased, so I guess it did some good.

Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for United States President promising to end Prohibition and shortly after he won the office, passed the Cullen–Harrison Act. This allowed for the sale of 3.2 percent beer and wine, which they thought for some reason was too weak to make anyone actually intoxicated. (In reality, it meant that people had to drink twice as much of the stuff for the same buzz they used to get.) But, hey, at least people could run down to their local store and legally buy themselves some beer, right?

It wasn’t long before the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified, pretty much nullifying the Eighteenth Amendment and The Volstead Act.

Cincinnati has long been known as Porkopolis (The Pork Capital of the World) a title it may truly deserve. However, in many ways, the Pork industry doesn’t come close to the impact that breweries had on the state (or the nation). But, I suppose the Pork Capital sounds better than the Drunk Capitol, so maybe let’s let this one slide?

Before Prohibition, Cincinnati had to have been somewhere on the top of those Wettest Places In America lists. Alcohol consumption is said to have been at least twice the national average. The German population could have had a lot to do with that (you know the Germans and their Beer) but that’s not the whole story. Still, by some accounts there was one saloon or pub for every 41 adult males (who were old enough to enter).

After Prohibition, Cincinnati … well, things had changed. In the months between the Cullen-Harrison Act and the ratification of the 21st Amendment, only a handful of breweries tried to open. Now, Prohibition did have a negative impact on legal breweries (and a positive impact on illegal ones) but that hardly explains why Cincinnati was so slow to reopen the bigger breweries. Cincinnati residents (even the Non-German ones) still liked their beer, after all.

It may seem counterintuitive, but there is a good case to be made that part of the reason not too many breweries reopened post-prohibition was because the need was too great. Most felt like they needed to expand their operations to get on top of the game, but lacked the resources to do so. And the smaller breweries were just that – too small.

It would take time (and a lot of different factors) for that to eventually come around, at least to some extent. And sometimes, help came from some, well, unusual places.

Wiedemann’s Brewery, located across the Ohio River in Kentucky was owned and named after a fellow with an absolute obsession with America’s newest pastime: baseball. He also happened to own and run a (non-League) Baseball Team – The Brewers. (Not to be confused with the Milwaukee Brewers who won’t come into existence for a few decades yet.)

Wiedemann loved his baseball team so much, he made sure he gave them the best of everything. People wanted more comfortable seats, he gave them that. People wanted lights in the stadium so the games could be played well into the evening … sure, not a problem.

Meanwhile, across the river in Ohio, the Reds were playing at Crosley Field without lights or comfortable seats, or any of the other innovations The Brewers field in Kentucky were enjoying. So, The Reds set out to innovate, updating their stadium, and … making deals with local breweries because, damnit, Baseball and Beer should go together like Bread and Butter. And, if you’ve ever gone to a recent ballgame and spent twenty bucks on a mug of beer the size of a Dixie Cup, I think you’ll know how well that turned out.

Bill and Bob

One of the most overlooked aspects of prohibition (or, perhaps saying Temperance would be better) were in something known as Penitent bands. This was a Methodist practice of meeting in groups on a Saturday night to talk about things, confess your sins, and … well, if you were in a penitent band, that means you weren’t out gambling or drinking or doing any of the things nice Methodists weren’t supposed to do.

In Ohio, penitent bands seemed to rise in popularity in the years before prohibition, and even continued afterwards. Eventually these bands started to wane in popularity, but some are still in existence today.

Meanwhile, over in England, American Lutheran minister Frank Buchman started the First Century Christian Fellowship, which was later renamed to The Oxford Group. Part of what this group did was to provide activities meant to avoid temptation of ungodly things, as well as developing a religious system of self-improvement requiring the individual to practice several steps in order to turn one’s life around.

Fast forward to the year 1934 and this American named Bill Wilson is across the pond, and he just happens to like alcohol a bit too much. Long story short, he gets introduced to The Oxford Group by some people who think that maybe a group like this could help him not drink so much. See, Bill didn’t want to drink, but for some reason he felt he couldn’t control himself. And, when he was drunk, he did stupid things that he wouldn’t have done were he sober, and oh man his life had become unmanageable.

The following year, Bill’s business brings him to Ohio (Akron) and while he’s here, he really wants to get drunk and do stupid things, but The Oxford Group is so far away … but, he managed to get in touch with some people he knew through the group here and eventually he comes into contact with a doctor named Bob. Seems Bill thought the only way to stay sober was to hang around with another drunk, especially one who also wanted to stay sober, as if that was a good idea.

So, Dr. Bob hung out with Mr. Bill, the two attended a few penitent bands, and they tried to come up with something that would essentially cure their alcoholic tendencies. Eventually the two merged the ideas behind the penitent bands with the ideas from the Oxford Group and thought maybe they had hit on something big. Mr. Bill moves in with Dr. Bob and his wife, and things are all find and dandy until Dr. Bob goes off to a medical conference and drinks himself into a stupor. But, after he comes home, he talks with Mr. Bill a bit more, and on June 10, 1935, Dr. Bob has his last alcoholic drink. Together Bill and Bob had developed a program, a system for helping people who didn’t want to drink anymore. And all it took was for the person to go through twelve steps – steps that may seem easy at first glance, but with honest reflection, weren’t all that simple.

Somehow, though, it worked.

That group, in case you didn’t catch my subtle clues, is still in existence today and is known as Alcoholics Anonymous.

Ohio Today – Wet or Dry

Since Ohio appeared to be on the forefront of the anti-alcohol side of history, it kind of surprised me to realize that not a single county in Ohio is “dry”. However, there are some municipalities that are dry, but … there are just three: Albany (in Athens County), Porter Township (in Scioto County) and Portsmouth (also in Scioto County).

For the most part, the state liquor laws appear to be at least somewhat typical … in other words, a confusing jumble of words that are sometimes contradictory and I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice.

According to Ohio Laws, it is illegal to have an open container of alcohol in publicly accessible places. Ok, sounds good. When I’m down at the park with my kids, I don’t want a group of rowdy drunks coming over to blow raspberries on their tummies. But, wait a second. Also according to Ohio Law, my front porch is considered a publicly accessible place since I don’t live in a gated community… so, are you trying to tell me that it is, technically, illegal for me to sit on my front porch and watch the sunset while enjoying a Fig Newton (a delicious cocktail made with equal parts Skyy Vodka and Apple Schnapps and served with a dried fig or a splash of fig juice). Technically, yes, that would be illegal. However, the law is still unclear as to how much trouble I would be in and why.