On September 24, 1990, the world’s attention shifted to Cincinnati, Ohio for what was surely going to be among the most controversial trials the city had ever seen. On the surface, it’s simply a trial about obscenity. But, for both sides of the issue – it’s about a lot more than that.

On one side is a group of people who believe that “Art” should be held to a high moral standard. Many of them have witnessed society, in general, becoming more and more secular, with laws being enacted that go against their religious teachings to some degree. And this hasn’t always been about art. For example, their views on marriage were defined as being “until death do us part” and many of them could remember the time when divorce was a major scandal (if permitted at all) but now it was becoming commonplace. Most felt as if their way of life was under attack, not just their religious and societal viewpoints. So, a case like this could be a major victory for their camp, if they could just win this one battle.

On the other side is a group of people who believe that “Art” is just art and should be protected as free speech. For many (but not all) of them, the issue wasn’t about religion, but freedom – although religious values often played a role. For example, many people in this camp were members of various minority groups, weather protected classes at the time (such as Jews or other non-Christians) or unprotected classes (such as homosexuals or “unwed mothers on welfare”) who felt personally attacked by laws and policies that were clearly set out to enforce certain religious values on secular society.

The question at hand was, to put it mildly, to figure out whether seven photographs on display at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center could or should be shown to the public.

Or, maybe another way to put it is, “Should pornagraphic artworks be considered art, or porn?”

The Myers Test

The Three-Prong Obscenity Test is also known as The Miller Test because it was developed from a different court case: Miller vs. California.

That case came about because of a mail order business in California, owned and operated by a man named Marvin Miller, that dealt in pornagraphic books and movies. When Miller mailed out some brochures, several were sent to a restaurant in Newport Beach (also in California) the owners of which were offended by such graphic pictures of heterosexuality. Because of this, Miller was arrested for violating California Penal Code 311.2(a), which said you can’t mail stuff that is offensively obscene (or, obscenely offensive, one of the two, or both, I’m no legal expert.)

During his trial, the jury was instructed to use whatever “community standard” they felt should be used to determine if this material was offensively obscene. The problem with this (or, one of the problems, anyway) is that one person’s “obscene” is another person’s “titillating adventure” so this is likely what Miller’s legal team was thinking when they appealed after getting a guilty verdict.

To make a long, boring (except to legal nerds) story a bit shorter, this case worked its way through the Untied States Supreme Court, one result being the Three-Prong Obscenity Test, or The Miller Test, which says that in order to be (legally) obscene, three criteria must be met:

- whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest;

- whether the work depicts or describes, in an offensive way, sexual conduct or excretory functions, as specifically defined by applicable state law; and

- whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

The court determined that Miller’s conviction was unlawful (mostly because of the third prong) and sent the case back to the lower court, who promptly dropped the issue and released Miller from prison.

The Perfect Moment

So, back to the issue at hand…

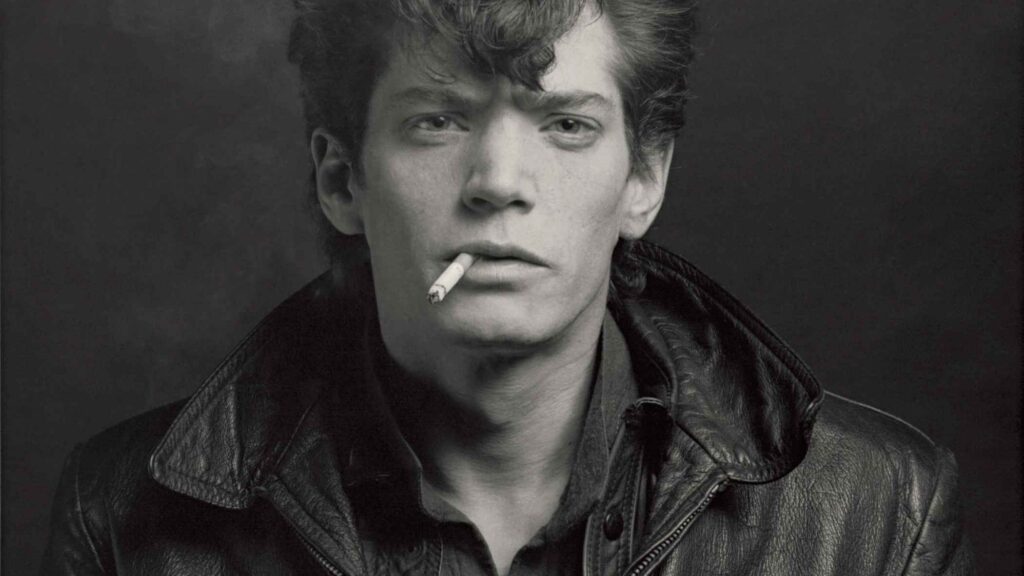

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989) was an artistic photographer who went from taking photos with a Polaroid Camera to photographing celebrities and having his artworks featured in art galleries. While the vast majority of his artwork is perfectly safe to hang in your office cubicle, he is also known for his more risque photos which heavily feature male and female nudity (sometimes but not always with sexual overtones) and he seems to have had a particular interest in the homosexual leather-BDSM community.

Looking at his photos, one is instantly aware of his artistic talent. It doesn’t matter if we’re looking at photos with titles like Blondy (Debbie Harry) or Richard Gere or William Burroughs or one of his numerous flower-based photos, or even something like Banana (which features a set of keys hanging from a banana) … it’s clear Mapplethorpe was an artist with an incredible talent. However, he’s also known for other, not safe for work kinds of photos, such as Man In Polyester Suit, Marcus Leatherdale / Erection, or Lisa Marie, (Breasts) we start to see one of the ways that he tried to expand the artistic paradigm.

The Perfect Moment was first created by Mapplethorpe and Janet Kardon of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Philadelphia which opened a few months before the artist’s death and featured a wide selection of 150 of photos taken throughout his career. The exhibit then traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and then it almost made it to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. but the exhibit was canceled a mere two weeks before it was set to open.

There was no controversy to speak of in either Philadelphia or Chicago and both cities tended to give more favorable reviews. Perhaps Washington D.C. was different because of the ideological shifts in Post-Regan America. It quickly became a hot topic of conversation and debate between liberal and conservative politicians and both sides wanted to use the photos as an example of everything that was wrong or right about modern life.

Part of the outrage came from public funding for art exhibits through the National Endowment for the Arts. For some, the very thought of national funds going to support obscene or pornographic images was just too much to bear. Senator Jesse Helms tried to introduce new legislation that would, effectively, block the NEA from promoting or supporting anything obscene. If passed, artists wanting to associate with the NEA would have to sign an oath promising not to promote obscenity and this proved too much for the artists to bear.

While the Helms Bill did not ultimately pass, they were at least slightly successful in changing the petition process for artists looking to the NEA for help.

There was one thing that everyone knew – this battle was not over.

The Perfect Moment Comes to Cincinnati

From the moment that it was announced that the next stop for The Perfect Moment was to be the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in Cincinnati, Anti-Pornagraphic and “Family Values” groups began to pressure its director, Dennis Barrie, to cancel the exhibit. Barrie, on the other hand, was trying to bridge the gap between Modern Art and Pop Culture, and most likely appreciated the controversy, at least in theory. Needless to say, he wanted the show to go on.

Opening day was, as you would expect at this point, a fiasco.

Outside the museum, a number of groups lined the streets, holding bibles, and shouting at those who choose to enter the building. Preachers got on their soap boxes (literally) to profess the word of God. And, slightly further away, more liberal groups were there to counter protest, although they went largely ignored by the media at the time.

With about four hundred patrons inside, the Cincinnati police arrived on the scene and issued an evacuation order. For the next hour, they videotaped the entire exhibit, spoke with museum staff, and all but interrogated Dennis Barrie. It wouldn’t be long before both Barrie and the Contemporary Arts Center were hit with criminal charges – for obscenity.

This was the first time in American history that an art museum faced criminal charges because of the content of the art it displayed.

On September 24, 1990, two sets of large legal teams started their battle in the courts. Both sides, the prosecution and the defense, wanted a bench trial with Judge F. David J. Albanese, as opposed to a jury (they can be unpredictable, after all) but the judge denied these requests. (Perhaps he didn’t want the political fallout from whichever side didn’t win?) What he actually said, though, was that he believed this case all hinged on The Miller Test, and that was going to be his guide.

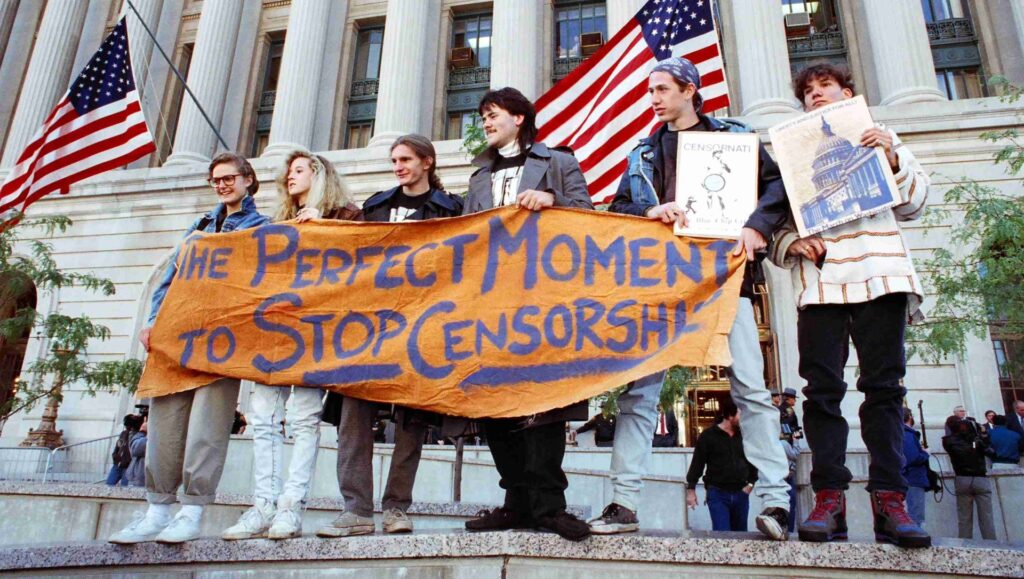

Outside the courthouse both the religious anti-porn activists and the freedom of speech folks gathered on the streets, even marching by important locations. Pastors led prayers and bible readings from the sidewalks or the courthouse steps as the liberal groups marched by holding signs in support of art or against censorship.

Inside the courthouse, potential jurors are being vetted, being asked questions such as whether or not they have ever read a Playboy magazine, or if they had ever attended an artistic fundraiser. Several admitted to have “read” Playboy or Hustler or Penthouse, however not a single one said they had subscribed. Likewise, not a single potential juror admitted to taking an art class or attending an artistic fundraiser.

That afternoon, the events outside the courthouse took a dramatic turn, literally, when protesters began enacting famous works of art that contained nudity (although it is reported they did have their genitals covered). Before the police could disperse the crowd, a “Cincinnati Version” of Michaelangelo’s The Creation and The Fall of Adam and Eve were performed. No arrests were made, according to the then chief of police, because the crowd moved on when they were asked to.

During the trial, however, most of the discussion was about things other than the central issue (whether or not those seven photographs were obscene, and therefore violated decency laws). Much of the talk was about things such as suppressing the gay rights movement, often with the reminder that AIDS was a punishment for an immoral lifestyle. They talked about the degradation of the family unit and how pop culture needed to be less mainstream and more God-focused. There was a discussion on nightly television about whether or not the general public should be forced to view gay porn, as if that issue was somehow relevant (nobody was forcing anyone to see the Mapplethorpe exhibit).

Early on October 5, 1990, the trial came to a close and the jury went out to deliberate. They returned a mere two hours later with a unanimous verdict – Not guilty on all counts.

The main question they had to ask themselves was if those seven photographs had artistic value, even if they, themselves, didn’t particularly enjoy viewing them. It did not take them long to say that yes, the photographs had such artistic value, therefore they all passed The Miller Test and ultimately no laws were violated.

Beyond Mapplethorpe

When looking at The Mapplethorpe Case, it’s important to remember that in many ways, the world was a bit different back then. This was well before “the internet” was really a thing (although its predecessor was doing quite well, thank you very much) – which meant that not only were naughty magazines and videos a little harder (but far from impossible) to get your hands on, but people usually only interacted within their own social circles, which usually revolved around neighborhoods, schools, and churches. Differing viewpoints about things were not frequently expressed because people tended to surround themselves with those who felt or thought the same way they did.

Mainstream attention to the gay community, for example, painted that community in a less than favorable light. The vast majority of attention was due to the AIDS Virus, and without proper education a lot of people still strongly believed they could get it from a toilet seat or if they parked their car next to someone at the Drive-In even if they kept their windows up. (Not really, but I’m sure a few people did.)

Daytime talk shows were starting to get bored with the same old same old (How To Cook The Best Pot Roast … or … How Do Discipline Our Daughter For Getting A C On Her Report Card) and had already started to shift to subjects more controversial or titillating, even if most gay positive subjects were still too hot for TV.

In Sitcom Land, few shows dared to include any topic that would make homosexual seem acceptable, although there were a few. Night Court had an episode where Harry tried to hook up with a reporter who turned out to be a lesbian … and while Designing Women’s “Killing All The Right People” episode had good intentions (the ladies are tasked with designing a funeral for a man about to die from AIDS) today the episode is just one more example of the “Kill the Gays” trope.

Looking back (if only The Streisand Effect was a thing back then) the victory for the liberal views, and in particular the LGBTQ+ community, became a lot more energized following the acquittal. The nation’s eyes were on this trial and it sent a message that many had been waiting a lifetime to hear.

While a large part of public sentiment was firmly against the Contemporary Arts Center’s display of the Mapplethorpe exhibit, signs were beginning to indicate that the tide was shifting, even if by a small bit.

The artist community, however, was the most vocal in their victory lap with some saying this was a major win for the war against censorship, some even commenting that The Mapplethorpe Trial was proof that The Bill of Rights extended to them, too.

Throughout the 1990s (who am I kidding, it’s still going on today) there have been other attempts at artistic censorship, outrage over things called or perceived as “obscene” or “pornagraphic”. However, none of these really rose to the prominence that The Mapplethorpe Trial did, and it soon became crystal clear that most often, the more outrage over something, the more the general public wants to see it for themselves. (For example, 1992’s Basic Instinct, which some groups tried to call pornagraphic, tasteless, leud, and a number of other things, which only seemed to heighten the public’s desire to find out which scenes Sharon Stone was wearing underwear in – and in this day and age of 4K movies, I can saw with utmost certainty that you really didn’t get to see her “business” in the legs crossing scene.)

Some people today say this idea of censorship and outrage over something a few people want to call “Obscene” or “Pornagraphic” is tedious at best and outrageous at worse. For example, when a certain senator-woman from Georgia declared that PG-13 rated delightful comedy (staring National Icon Robin Williams) Mrs. Doubtfire to be “obscene and pornagraphic” simply because it features a man pretending to be a woman – I am starting to think we’ve lost our way. But, thankfully, that is just my opinion.