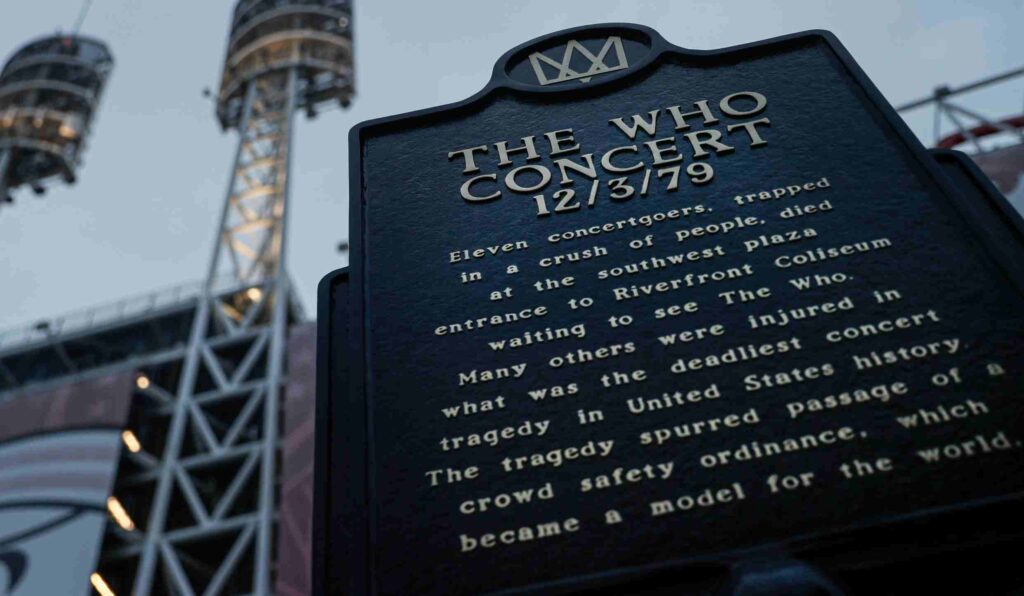

Believe it or not, Ohio has played a rather serious role in the history of Rock N’ Roll. Some of that history is awesomely good (for example, we’ve got The Rock N Roll Hall of Fame up in Cleveland) … but, sadly, some of it is not so good (such as The Who Concert Tragedy, the focus of today’s discussion.)

Cincinnati’s Riverfront Coliseum was built in 1975 and was no stranger to good ole Rock N Roll. The first concert to perform there included Muddy Waters and The Allman Brothers Band; two years later, 17140 people would see Elvis Pressley there (in his second-to-last performance ever). Of course, other types of music would play there as well, such as earlier in 1979 The Bee Gees were trying to keep disco (Stayin’) alive while also still trying to convince the world that singing in falsetto was somehow cool…?

By December 3, 1979, the British rock group The Who was at the top of their game. (Considering two decades later the band would allow a few of their songs to be used during the opening credits of all the shows that began with the letters CSI: I’d say the group is still going strong.) And, if you were anywhere close to Cincinnati, you knew they had a concert going on. Radio stations were holding contests for tickets, television stations were hyping the concert, and clearly, this was going to be the biggest concert the city had seen since, well, the Brothers Gibbs had been there.

How Not To Do A Rock Concert

By three o’clock that day, crowds began to assemble outside the arena and all was well until about five o’clock when only a single set of doors were unlocked to allow the public to enter. This caused a bit of confusion. All those near the only open doors tried to figure out how to go in, everyone near the other doors wondered why their doors weren’t unlocked, and people farther away didn’t know what was going on or why the lines didn’t seem to be moving all that fast.

Another thing to consider is that at that time Riverfront Coliseum, like most concert venues, used general or festival seating. In other words, they weren’t assigned seating, so if you want good seats, you gotta get there early and hope you get lucky.

There is some dispute over what, exactly happened next. Some people say that the band was doing a last-minute rehearsal, others say that The Who’s film Quadraphenia was playing in the auditorium, while others thought maybe it was a soundcheck of some sort. But, no matter the cause, the result was the same.

A bunch of people got confused and believed the concert had started without them. Now, everyone wanted to get as close to the stage as possible, even if that meant pushing the person in front of you, who likewise was pushing on the person in front of them…

Eleven people died from compressive asphyxia (their lungs could not expand with the air needed to breath because the venue was so tightly packed). Several others were severely trampled and needed emergency medical attention.

How Not To Handle Tragedy

Fire officials arrived at the Coliseum and began talking to the band director, Bill Curbishley, as Emergency Medical Technicians began to attend to the injured and deceased. While the fire chief wanted the concert canceled or postponed, the band’s management team wanted the show to go on. It wasn’t until Curbishley brought up his belief that the crowd would panic further if they stopped the show that the concert was allowed to go on as scheduled.

Before the show, the band themselves was not informed that eleven people, all children or young adults, had been killed and that many more had suffered injuries. Several band members went on to say that had they known before the concert, they would not have gone on stage that night.

When informed of the tragedy, the members of The Who weren’t happy. They were angry at a large number of people, including the venue organizers who failed to open enough of the doors to allow over 18000 souls to enter safely and for the lack of security, they were angry at their band management team who allowed the show to go on. They were very concerned that this had happened, and feared that it might happen again.

Over the next few days, the media was saturated with stories and commentary about the event (and only a small bit of that seemed to focus on the eleven individuals who did not come home that night – Jacqueline Eckerle, 15; Karen Morrison, 15; Bryan Wagner, 17; Peter Bowes, 18; David Heck, 19; Stephan Preston, 19; Philip Snuder, 20; Connie Sue Burns, 21; James Warmoth, 21; Walter Adams, 22; Teva Rae Inlow Ladd, 27.

Walter Cronkite devoted a large segment of the CBS Evening News to examining violence at rock concerts while another station seemed to place the full blame on Rock and Roll itself, including a line from an interview that suggested that if children listened to more christian music, none of this would have happened. The fire marshals were criticized for allowing the concert to continue, and the coliseum management for their series of poor decisions. There were so many places that people wanted to blame it was, at least for a short while, difficult to know what to think.

How To Learn From Mistakes

The very next night, The Who was scheduled to perform in Buffalo, New York and just as they began their concert, the members took to the stage and band members addressed the audience. “We’re in the wrong city,” guitarist Pete Townshend said before he and the band dedicated the show to the eleven dead in Cincinnati. “We lost a lot of family last night. This show’s for them,” they said.

Cincinnati, officially, outlawed unassigned seating at concerts immediately following the tragedy. This would hold for the next 25 years.

Families of the victims sued the band, Electric Factory Concerts, and the city of Cincinnati which was eventually settled a few years later, awarding each family $150000, although the Boyles family opted out and settled for an additional (and unknown) amount. Another three quarter of a million dollars was to be split between all the injured.

In 1981, John Grant Fuller published a book, Are the Kids All Right? The Rock Generation and Its Hidden Death Wish that examined the tragedy while also focusing on the role that Rock and Role culture played in the events.

On February 11, 1980, a “very special episode” of the television show WKRP in Cincinnati was aired, titled “In Concert” in which the sitcom characters reacted from their fictional radio station as the events played out in another part of the city.

For most people, however, this disaster was a much needed wake-up-call. Parents started to consider the safety of their children, no matter where they went. Cities started to better consider the safety of their citizens and visitors. Event producers began to take second looks at what they were doing and how they were doing it.

Concerts, in general, were greatly changed between the 1970s and 80s – and this disaster had a lot to do with it.

Pingback: Fictional Ohio - WKRP In Cincinnati - The Ohio Project